UC

Berkeley expert on insect flight receives prestigious MacArthur "genius"

award

24 October 2001

By Robert Sanders, Media Relations

BERKELEY —

A University

of California, Berkeley, professor whose e-mail moniker is "flyman"

and who has become one of the world's experts on the aerodynamics of

flying insects was named a MacArthur "genius" Fellow today (Oct. 24).

|

Michael

Dickinson, UC Berkeley professor of Integrative Biology and MacArthur

Fellow

|

Michael H. Dickinson,

38, professor of integrative biology in UC Berkeley's College of Letters

& Science, was among 23 new fellows announced today by The John

D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Each will receive $500,000

over five years, to spend as they wish.

The MacArthur

Fellowships, often called "genius" awards, are awarded each year to

creative individuals "who provide the imagination and fresh ideas that

can improve people's lives and bring about movement on important issues,"

according to Jonathan Fanton, president of the foundation.

Dickinson was

the last of the new MacArthur Fellows to be notified of the award. He

was reached over the weekend by a cell phone voice mail while backpacking

along the remote Na Pali coast of Hawaii. He had to scratch the foundation's

phone number in the sand, but the cellphone shorted out in the dampness

before he could call back.

He finally contacted

the foundation yesterday from a pay phone at Kokee State Forest, where

he had gone to see "wild Drosophila (fruit flies) swarming through guava

forests. It's a total blast. Everybody comes up here for the birds,

but all I want to see are the flies."

Thrilled by

the award, he said, "It's all kind of surreal. I figure that for the

rest of my career everyone in the lab is going to start each sentence,

if you're such a genius, why can't you ...."

Dickinson refers

to himself as a neuroethologist. He studies the nerve and muscle connections

that allow flying insects to maneuver so expertly that they are among

the most versatile and sophisticated of all flying animals.

The principles

he uncovers are even now being applied to the development of tiny flying

robots that have potential use in search and rescue, environmental monitoring

and remote sensing.

|

|

|

"Flies

are nature's fighter jets ...They're arguably the most aerodynamically

sophisticated of all flying animals."

--

Michael Dickinson

|

| |

|

|

|

"Flies

are the most accomplished fliers on the planet in terms of aerodynamics,"

Dickinson said. "They can do things no other animal can, like land on

ceilings or inclined surfaces. And they are especially deft at takeoffs

and landings - their skill far exceeds that of any other insect or bird."

To study insect

flight, he has built some amazing contraptions. One is a virtual reality

"flight arena" for flies, in which he displays various moving scenes

to tethered flies and records their wing motions. "Fly-o-rama" is like

a small circus tent in which he records in three dimensions how a fly

moves in response to various stimuli. Variations on these themes include

a "rock-and-roll arena" in which he studies fly responses to mechanical

stimuli, and "smell-o-vision," where visual stimulation is combined

with food odors, such as vinegar.

He also constructed

10-inch long models of fruitfly wings - 100 times normal size - and

immersed them in a vat of mineral oil to study the currents and vortexes

set up by their wing motion.

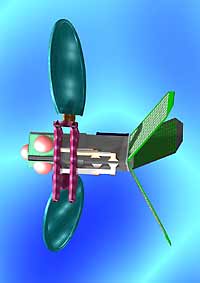

This model,

dubbed Robofly, enabled him to break down flies' rapid wing flapping

into three distinct wing motions that not only allow insects to stay

airborne, but also let them steer and execute amazing acrobatic maneuvers.

These mechanisms, much different from the mechanisms used by birds and

airplanes, seem to be common to most insects, and perhaps even to the

hummingbird.

"This robotic

fly enables you to resolve questions about how insects manage to fly

that are impossible to address otherwise," said George Lauder, professor

of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University and an

expert on how fish swim. "Michael is the only one I know who has quantified

the forces on a moving biological appendage."

In other experiments

he and his laboratory colleagues dissect fly flight muscles and nerves

to tease out their interconnections or to record electrical signals

from them.

"There is nobody

in the world who has the range of expertise, from neurophysiological

approaches through fluid mechanics, that Michael has," Lauder said.

Ron Fearing,

professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley, leads a team now

building a micromechanical flying insect based on the principles that

Dickinson has discovered.

"It is Michael's

aerodynamic breakthrough that is going to make our micromechanical flying

insect possible," he said.

|

In

the multimedia web site "Fly-o-Rama"

produced by UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism student Jason

Spingarn-Koff, hear Michael Dickinson describe his work and see the

ingenious experiments and simulations he has devised in order to understand

and replicate insect flight. In

the multimedia web site "Fly-o-Rama"

produced by UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism student Jason

Spingarn-Koff, hear Michael Dickinson describe his work and see the

ingenious experiments and simulations he has devised in order to understand

and replicate insect flight.

|

Dickinson has

a background in both neurology and zoology. He obtained his bachelor's

degree in neural science from Brown University (1984) and his PhD in

zoology from the University of Washington (1989). Following a series

of postdoctoral appointments he joined the University of Chicago faculty

in 1991, leaving for a tenured position at UC Berkeley in 1996. He became

a full professor in 2000.

Born in Seaford,

Del., he grew up in Baltimore and Philadelphia. Originally intending

to pursue sculpture when he entered Brown University, he switched to

neurobiology because of his fascination with the mechanisms that underlie

animal behavior.

His honors include

a graduate fellowship from the National Science Foundation (1985), the

Larry Sandler Award from the Genetic Society of America (1990), a Packard

Foundation Fellowship (1992), and the George Bartholomew Award for Physiology

from the Society of Integrative and Comparative Biology (1995).

He lives in

Berkeley, California.

Additional information:

|