|

Berkeley/NASA

satellite to launch February 5 on mission to study solar flares

31 January 2002

By

Robert Sanders, Media Relations

|

|

|

A

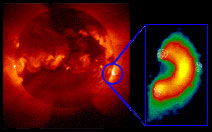

1992 picture (left) of the two million-degree solar atmosphere glowing

in soft X-rays, taken with the Soft X-Ray Telescope on the joint

Japan-U.S. Yohkoh mission. At right is a blow-up of a flare as seen

with Yohkoh in soft and hard X-rays. (hi-res

version)

NASA

photo

Additional

information for the media

|

Berkeley

— A satellite

dedicated solely to the study of solar flares and designed, built and

operated by an international consortium led by scientists at the University

of California, Berkeley, is set for launch on Tuesday, February 5, by

the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

The High

Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager, or HESSI, will embark

on a two- to three-year mission to look at high-energy X-ray

and gamma ray emissions from solar flares — enormous

explosions in the solar atmosphere. Though various satellites

have made X-ray and gamma ray observations of flares, HESSI

will be the first to snap pictures in gamma rays and the

highest energy X-rays.

"With

intense flares, we can take X-ray images with very high

resolution, very fast, and create movies of flares lasting

from 10 seconds to tens of minutes," said Robert P. Lin,

professor of physics in the College of Letters & Science

at UC Berkeley and principal investigator for the mission.

Lin also is director of UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory.

Using

these images, plus X-ray and gamma-ray spectra with unprecedented

energy resolution, the scientists hope to discover what

triggers flares and how energy stored in the solar magnetic

fields is suddenly released to accelerate particles to very

high speeds and to heat the gases in the solar atmosphere

to tens of millions of degrees.

"From

these hard X-ray and gamma-ray measurements, we can reconstruct

the energy distribution of the particles and trace back

to where everything was accelerated," Lin said.

The mission

begins near the peak of the sun's 11-year cycle of activity,

providing an unprecedented opportunity for study of these

explosive events. What scientists learn will give insight

into the processes that accelerate other particles whizzing

at nearly light-speed through the universe.

HESSI is the sixth

Small Explorer (SMEX) spacecraft scheduled for launch under NASA's

Explorers Program. Total cost for the mission, including the spacecraft,

launch vehicle and mission operations, is about $85 million.

Solar

flares, along with the often associated explosions called

coronal mass ejections, are the solar events that most affect

"space weather." The intense energy associated with these

events — up to the equivalent of a billion megatons

of TNT — and the energetic particles they throw out

impact the Earth's magnetic field, compressing it and interfering

with radio communications on Earth. Astronauts and cosmonauts

aboard the International Space Station or the Space Shuttle

also can receive dangerous doses of radiation from the high-energy

particles.

|

| HESSI

project manager Peter Harvey. Lauren Garcia photo |

"Coronal

mass ejections sometimes have flares associated with them

and sometimes don't," said Brian Dennis, HESSI mission scientist

at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

"We don't understand why this should be or what the relationship

is between these two types of events."

The 645-pound (293

kilograms) HESSI satellite will be launched atop a Pegasus XL rocket

dropped from the belly of an L-1011 aircraft flying out of Cape Canaveral

Air Force Station, Florida. After the plane reaches an altitude of

about 40,000 feet over the Atlantic Ocean, the rocket will be released

to free-fall in a horizontal position for about five seconds before

igniting its first stage motor. The three-stage rocket will place the

spacecraft into a circular orbit about 373 miles (600 kilometers) above

the Earth, inclined at 38 degrees to the equator.

>>

continued

HESSI project manager Peter Harvey details satellite launch

and orbital insertion.

(requires

RealPlayer)

|