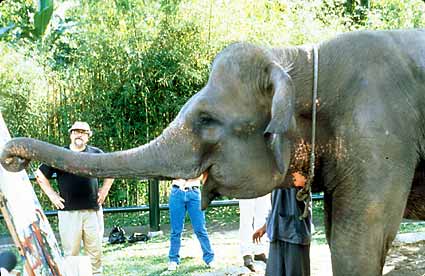

Arum,

an Asian elephant, at the canvas in Bali. Photo courtesy Goldie Paley

Gallery |

Russian conceptual

artists known for elephant art project spending spring semester at UC

Berkeley

25 March 2002

Michele

Rabkin, Consortium for the Arts

BERKELEY

-Two conceptual Russian artists known for teaching elephants to paint

and chimpanzees to use cameras are spending spring semester at the University

of California, Berkeley, instructing students about animal creativity,

totalitarianism and underground art.

Now residents

of New York City, Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid made a name for themselves

in the 1960s as young artists and dissidents at government schools in

Soviet Russia. Their wide and often controversial range of work includes

painting, performance, installation and advertising.

|

This

painting is by Nanchok, an Asian elephant. Photo courtesy Goldie Paley

Gallery

|

In 1998, they made

headlines for creating the Asian Elephant Art and Conservation Project,

recently featured on "60 Minutes." Komar and Melamid teach

elephants that once worked in Thailand's logging industry to paint,

then sell the paintings to raise money for the animals' care.

At UC Berkeley, the

artists are in residencies sponsored by the UC Berkeley Consortium for

the Arts, the Arts Research Council and the Department of Art Practice.

"The students

are having a delightful, robust, even controversial adventure with the

Russian team," said Mary Lovelace O'Beal, chair of art practice.

The artists are displaying

their elephant paintings, giving guest lectures in Slavic Studies about

totalitarianism, and will visit a biology class in April to talk about,

among other things, how they taught chimps to take photographs.

In one recent class,

students spent the session talking about performance art versus the "happenings"

of the 1960s, freedom of expression, being a spectator compared to a

participant, cloning Dali, and the changing public perceptions that affect

an artist's reputation.

Komar said their

art practice students have each been assigned to invent an artist –

a sort of hero or alter ego with no limitations. They will develop a

biography of this artist. One student is composing a whole new artistic

movement. The plan is to assemble their work in a book that they hope

to publish, and possibly display in New York City.

Reflecting on the

Asian elephant project, Komar said he and Melamid first began working

with elephants in zoos in the United States, teaching them to paint,

and also worked with chimps and cameras. But after reading about the

plight of elephants in Thailand, who fell on hard times after logging

was banned in 1990, they were drawn to help.

The project involves

draping animals in aprons and teaching them to paint wielding a brush

with their trunks. The resulting artwork, which resembles abstract expressionist

work, is auctioned, with a percentage of funds going toward proper care

for the elephants and support for their trainers. Some elephant paintings

have sold for up to $2,000.

"You have

to see this project as complexly related to the now common cry that painting

is dead and artists have gone on to other things," said Charles

Altieri, a professor of English at UC Berkeley and director of the Consortium

of the Arts. "What can we do with a dead art?

"Maybe we

can make it a live form of social intervention — in this case by

saving Thai elephants from destruction and actually making money for

a good cause. After all, it is arguable that what killed painting was

the gallery structure that created ridiculous myths and produced prices

for art that only the very few could afford. It is a nice irony that

what was ruined by profit motive can be restored as a kind of charity."

Modern art was

based in large part on the idea that art should have no practical purpose,

so artistic energies and development of materials could be appreciated

for their own sake. "What better way to celebrate the demise of

this modernist ideal than to develop a mode of painting that serves clear

and valuable social ends, without needing any rhetoric that it improves

anyone's soul," said Altieri.

He added that this

elephant art raises serious questions about what is art, why people collect,

and how we can link talk about the unconscious in art to the forms of

gesture that elephants produce on canvas. The more seriously we are tempted

to take these elephant paintings, the more ridiculous we are likely to

feel speaking about deep psychological meanings in all non-figurative

expressive work.

"And that I

think is their (Komar's and Melamid's) ultimate point,"

Altieri said. "They want us to wonder if there might be something

very odd and very wrong about the way that the high culture art industries

go about their work. But we also have to recognize that there is also

something very right about the possibility that this world is sufficiently

generous to give air time to elephants and apparently mad but brilliant

émigré artists."

Komar said when he

and Melamid finish their residency they will return to Thailand to continue

the elephant project. In November, they open a show in New York City

about spirituality in art. They also are contemplating a project involving

beaver architecture.

Meanwhile, at the

Berkeley Art Museum's Gallery 3, more than 50 paintings done by

16 Thai elephants will be on display, along with photos and documentation,

from April 10 through July 14.

A slide show lecture

by the artists about their elephant work and a screening of "The

People's Painting" video will take place at the Berkeley Art

Museum Theater at 5:30 p.m., Thursday, April 11. The film is a Komar-Melamid

project using information assembled from polls, focus groups and a road

trip through Great Britain to create a picture that would produce what

most people project as the painted images they most desire.

Additional information:

|