|

|

|

NEWS

SEARCH

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

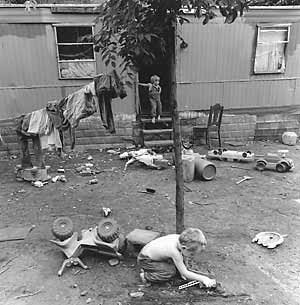

James

(front) and JR at their Thacker Hollow home in West Virginia's

coal country. (Photo © Ken Light)

|

Dying

coal industry, culture are focus of documentary project by UC

Berkeley photojournalist

9 August 2002

By Kathleen Maclay, Media Relations

Berkeley — While millions watched TV reports

of the recent rescue of nine miners in Pennsylvania, documentary

photographer Ken Light was just a state away, quietly photographing

the death of the coal industry and culture.

Each summer for the past three years, Light has packed his

camera gear and headed to West Virginia, the country’s

most impoverished state and a central location in the saga of

the nation’s shrinking coal business.

"Without coal, our world would die, and yet it’s

a completely hidden world, a fascinating place and an amazing

story," said Light, a lecturer at University of California,

Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism and curator of its

Center for Photography.

He has shot hundreds of rolls of film, making photographs of

West Virginia’s struggling mining communities and the remnants

of former coal company towns, visual records of "what’s

there, what happened and what’s left."

The pictures aren’t pretty.

| |

A

Ku Klux Klan rally outside the Jefferson County Court House.

(Photo © Ken Light)

|

The state where the first discovery of bituminous coal in the

United States was made, and where coal has been found in 50

of 52 counties, is blighted by extreme poverty, welfare families,

black lung and other disease, and a sense of hopelessness about

lost jobs and lost heritage, Light said.

In his visits, as he has tried to trace the roots of "coal

families", he has been invited into homes with retired

miners and their families, attended church tent revival meetings

held outdoors, watched wandering wrestling matches, and recorded

devastating summer floods.

He met a revival "snake charmer" with arms crippled

by almost 160 rattler bites, and was invited into "the

hollows" with a young man who leaned against his truck

to shoot OxyContin, a powerful prescription drug known as "hillbilly

heroin." He has attended a Ku Klux Klan meeting. The homes

of many families, Light said, are no longer traditional wood-framed

structures built on a lot, but trailer homes that can be pulled

from place to place. "The physical house as we know it

is gone," he said.

Although more coal than ever is being removed from the Earth,

fewer and fewer miners have been required in the retrieval of

coal since the introduction of mechanized equipment around 1950.

What once took 100 men now takes one man and a machine, Light

said.

A

"holy roller" tent revival meeting. (Photo ©

Ken Light)

|

|

The work of a coal miner has always been physically demanding

and often debilitating. Yet for generation after generation,

young men have followed their fathers into the mines. Now the

coal industry is a shadow of its former brawny self.

"It’s like cotton in the South. It’s been totally

mechanized and it hasn’t been replaced, there’s nothing,"

Light said. "So you have a culture that’s lost, there’s

kind of a longing for that."

California’s energy crisis and George W. Bush’s presidential

campaign comments about a coal comeback buoyed hopes in West

Virginia, Light said. But mining company executives were more

interested in importing "guest workers" from the former

Soviet Union, Peru and China than in hiring locals at union

wages. Meanwhile, the energy crisis on the West Coast was averted

and West Virginia’s coal industry continues to deteriorate,

Light said.

When Light is done with his photography in coal country, he

plans to assemble an exhibit of his work and publish the photos

in a book, along with personal stories written by his wife,

Melanie.

He is author of five monographs, including "Texas Death

Row," "Delta Time" and "To the Promised

Land." His latest book, "Witness In Our Time," featured

22 interviews of photographers working in this genre. His work

has appeared in Granta, Time, Newsweek, Fortune, Mother Jones,

The National Journal, Speak, L'Internazionale, Camera Arts and

other magazines.

|

|