| |

PEDALing

into the Future: Three applications

Gecko-inspired

adhesive

|

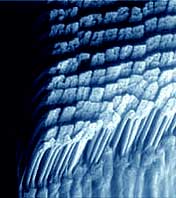

Closeup

(magnified 700 times) of the tiny hairs, or setae, that

line geckos' toes.

|

| |

The

branches, or spatulae, on the end of a single gecko

seta, magnified 30,000 times.

Photographs

by Kellar

Autumn, an assistant professor of biology at Lew

& Clark College and former UC Berkeley graduate

student who is now a collaborator with Full.

|

How

geckos manage to walk on walls and across ceilings has been

a mystery for many years. Some scientists speculated that

the lizards' feet relied on a layer of water whose surface

tension created sticking power. But working in the PolyPEDAL

Lab, Full gained a greater knowledge of the structure of a

gecko foot, which has millions of microscopic hairs (called

setae) on its bottom. These tiny setae span just two diameters

of a human hair, or 100 millionth of a meter, and each seta

ends with 1,000 even smaller pads at the tip.

As

they announce in an forthcoming journal article in the Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences, Full and other researchers

from Lewis & Clark College, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara

and Stanford University have developed synthetic copies of

the tip of one of these microscopic hairs, using two different

materials. By doing so, they have ruled out water adsorption

as the source of the sticking power, concluding that the setae

instead take advantage of Van Der Waals forces (weak intermolecular

attraction) to adhere temporarily. (For details, read the

press

release.) "We confirmed it is geometry, not surface chemistry,

that enables a gecko to support its entire body with a single

toe," says Berkeley engineering professor Ron Fearing.

That means the adhesive can be made out of any material.

Why

so much fuss over a gecko toe? It turns out that when grouped

together, these setae could outswing Spider Man. A single

seta can lift an ant a hundred times the seta's weight. A

million setae, which could easily fit onto the area of a dime,

could lift a small child. And it could do this without leaving

a residue, latching on faster and more easily than Velcro.

A

dry, self-cleaning adhesive like this would have many commercial

applications. The team has filed patents and is partnering

with several companies to develop a reusable adhesive material

that could be applied in a number of ways, from transporting

semiconductor chips through a factory's vacuum chamber (using

suction devices can scratch the chips), to moving fiber-optic

pieces through the human body for surgery and attaching equipment

to the exterior of a space station. Or, artificial setae could

help build the most mobile robot yet — unfazed by slippery

vertical surfaces and able to hang from the roof by a single

hair.

Artificial

muscles

The

self-stabilizing principles identified by Full have changed

the way researchers think of artificial muscles, whether as

part of a robot or a future human prosthetic.

Early

artificial limbs have resembled unwieldy Terminator-strength

steel joints with wire tendons. To move in concert, these

limbs have been computer-guided. But as it turns out, it's

possible to get a two-legged robot with artificial muscles

to walk without a brain, merely by making its muscles out

of a flexible, springy material and setting the tension carefully.

"If

you set the muscles right, so that just as the leg extends,

it stretches the muscles a little bit to stop the motion,

and then if you time it right to sit it back down, you can

get remarkable stability," says Full.

Full

is working with SRI International to see if simple pieces

of acrylic or silicone, when activated appropriately, will

operate in the same fashion as real muscles do. In the future,

"instead of having all those separate parts and a big

motor that runs them — something you attach to a prosthetic,

for example — you'll have something more lightweight,"

says Full. "At a joint right now, a single motor pretty

much dominates the whole joint. Eventually you'll be able

to put 10, 20 artificial muscles together and have much more

sophisticated control."

Robots

Forget

the Jetsons and their robot maids. Full is more interested

in what thinking machines can do to help humans in distress.

"One of the things we hope robots will be useful for

is search and rescue," he says. "A small, multilegged

robot should be able to go into a troubled area, whether the

result of an earthquake or bombing, and search for individuals.

Imagine a swarm of insects quickly going in to check for life."

The PolyPEDAL Lab is working with engineers to integrate antennae,

eyes and sensors that feel and detect heat into the current

crop of robots. Ariel, developed by iRobot in collaboration

with Full, can already locate mines lying on the sandy surface

of the surf zone. Future ant-sized robots, similar to ones

that Berkeley engineering professor Kris Pister is working

on, could perform microsurgery.

In

the near term, Full sees robots and robotic devices

extending the reach of the electronic world. "We

can already see other places remotely, through the Internet,"

he says. "What if we could actually do things

there? Robots could give the Internet legs and hands."

|

|