|

|

|

NEWS

SEARCH

|

|

|

|

|

EXTRAS

|

|

|

|

| Center

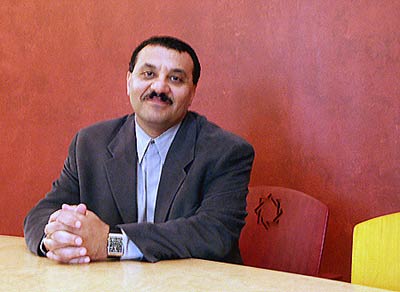

for Middle Eastern Studies Chair Nezar AlSayyad, in the

conference room that he designed for the center; he is also

a professor of architecture and planning. Photos by

BAP |

Middle

East 101: Q&A with Professor

Nezar AlSayyad, chair of UC Berkeley's Center for Middle Eastern

Studies

AlSayyad

talks about the Middle East's political and cultural diversity,

women's rights, why Arab states oppose Iraqi regime change,

and why Islam is here to stay.

15 October 2002

By Bonnie Azab Powell, Public Affairs

BERKELEY - With the U.S. Congress authorizing the use

of force against Iraq, the Middle East is on everyone's minds.

Yet few of us can name all the countries that make up the region,

or even begin to describe their histories and governments. As

part of an ongoing series about the region, we turned to one

of UC Berkeley's experts, Nezar AlSayyad, who has been chair

of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies since 1995, for a crash

course in the Middle East.

AlSayyad did his undergraduate work in architectural engineering

at Cairo University, a master's in town planning also at Cairo,

followed by another master's in architectural sciences at MIT,

and a Ph.D. at UC Berkeley in the history of architecture and

urbanism. Although directors of Middle Eastern Studies programs

often specialize in history or political science, AlSayyad's

urban history background is not that unusual: several Middle

Eastern centers in the U.S. are currently headed by faculty

from art history, architecture, or urban planning.

UC Berkeley's program, however, stands out for several reasons.

The university's curricula has included Middle Eastern Studies

for more than a hundred years. The Center offers courses in

Arab, Islamic, Jewish, and Israeli Studies as well as in languages

— among the most diverse offerings at any university.

Tell us where the catch-all name

"Middle East" comes from, and to what it actually

refers.

The Middle East is the only area-study discipline that lacks

easily drawn geographic boundaries, as in Latin American or

Southeast Asian studies. The Middle East is the "middle"

of what and "east" of where? Of course, it’s

east of Europe — east of the former empires that colonized

it — although technically it's also south. The reason

they called it the "middle" is because they also had

the "Far" East.

The issue of what actually constitutes the middle is still up

for debate. When the Soviet Union collapsed, we in Middle Eastern

Studies suddenly inherited all its southern republics. Why?

Because the people in those republics speak Turkic languages

and in terms of culture, are much closer to Turkey than to Russia.

So at least according to the U.S. Department of Education, which

funds most Middle Eastern Studies centers, the borders of what

we called the Middle East extended all the way from Morocco

in the far west to Uzbekistan in the east, and from Chechnya

in the north to Sudan and Somalia in Africa.

Without a common geography, language,

ethnicity, or even religion, what

unites this group of countries?

Like much of the Third World, it's a very specific history

and heritage of colonialism, institutions that were left behind

by either the British or the French when they colonized these

countries. There's also no doubt that Islam is another factor

that in a sense unifies the Middle East. Although Islam is not

the religion of all countries in the Middle East, nor does the

presence of Islam make a country Middle Eastern, by and large

the history of the Arab empire does happen to be also a history

of the Islamic empire. And it is an empire that extended in

a very short time, less than 200 years, to encompass precisely

this territory that I am talking about.

| |

|

|

'Clearly

there are Middle Eastern governments that are very dictatorial,

such as Saddam Hussein's. There are governments that are

oppressive. There are also ones that are trying their best.'

—Professor Nezar AlSayyad, CMES chair |

Another defining similarity is the nationalist struggles that

many of these countries have engaged in to free themselves from

their colonizers. But this last point is connected to something

else, which is maybe a fourth factor: the emergence of a particular

geography of political structure. Much of the contemporary Middle

East is divided into specific nation-states with international

borders that they did not choose, that were imposed as a result

of international deals the British and French made with tribes,

monarchies, and other regimes earlier in this century. Again,

the Middle East is not an exception in this regard — much

of the third world was also carved up the same way, but I think

you see it more in the Middle East.

You also have to remember that most Middle East countries did

not receive their independence until the 1950s and 1960s, unlike

other regions such as Latin America, which became independent

at the turn of the century and have had time for both unsuccessful

and successful experiences with self-government. In the Middle

East, that's really not the case. In these countries we have

gotten to see only two, maybe three generations of self-governing

elite. Egypt, throughout its entire modern postcolonial history,

has been governed by only three men. So has Saudi Arabia.

And yet their governments are very

different. Of the Middle Eastern governments, which are the

least and most stable — that is, enjoy the greatest degree

of acceptance among their citizenry?

Well, that depends on what you mean by "stable." Certainly

in the U.S. right now, there are people who do not accept the

legitimacy of the last election's results. Does that mean the

U.S. does not have a stable government?

In the Middle East, there's a considerable range. There are

governments that are obviously very dictatorial, such as Saddam

Hussein's. There are governments that are oppressive, because

they have social or political structures that oppress the population,

either using religion or other forms of social control.

There are also ones that are trying their best. Morocco has

liberalized quite a bit, both in terms of its democratic institutions

as well as its political structures. Today, one can talk about

Morocco, and even Lebanon, as democracies. It's a strange kind

of democracy, because it has ethnic and religious representation

almost embedded in its constitution, but there's absolutely

no doubt that it is a democracy.

I

would also point out that some of the governments that do not

necessarily give political rights to their citizens, or that

don't have a structure for political rights yet, have often

afforded their citizens a decent level of social and economic

rights. It's very difficult to think of the United Arab Emirates,

for example, as a place where there's democracy. But in reality

citizens of countries like Qatar or the United Arab Emirates

have possibly more press choices. They hear our CNN, the BBC,

and their own Al-Jazeera. And they can make up their mind about

what to believe. That is indeed a form of free press.

After

Afghanistan, many Americans seem to believe that Islam equals

repression of women. Can women work freely in

most Middle Eastern countries?

Even in Saudi Arabia, women are free to hold jobs. But there

are social traditions and specific conditions in some Arab countries

— like many others in the third world — that have

not allowed women to work or to be full citizens. However, in

others like Egypt, for example, women have held jobs since the

1920s and a woman served as cabinet minister as early as the

1950s.

In

terms of voting, in the case of Egypt, women have the same rights

as men. In Saudi Arabia or Kuwait, they do not. Aside from legal

rights, there are a lot of social pressures that inhibit women's

progress. For example, in Iran, the legislature recently passed

a law that allows women to get a divorce. But the implementation

of this law still has major obstacles along the way, mainly

because their religious leaders have the right to veto it, and

they will do everything that's possible to block it.

Next

page: Do

most citizens of the Middle East desire democratic government?

Page

1 | 2

|

|