Size changes of Bacillus spores could lead to simpler, faster anthrax detector

BERKELEY – The spores of a microbe closely related to anthrax swell with increasing humidity - a physical change that might allow quick and cheap detection of Bacillus spores like anthrax, according to physicists at the University of California, Berkeley.

The swelling is a surprise to microbiologists, who have assumed that spores of the Bacillus bacteria, which include anthrax (Bacillus anthracis), are a dormant, resting and basically inert stage of the microbe.

The swelling, observed of spores of Bacillus thuringiensis, bacteria now often used to kill insects that attack crops, may be diagnostic of all Bacillus spores and may allow scientists to distinguish between different types of Bacillus.

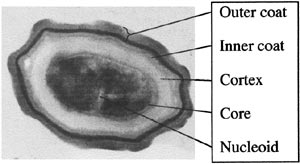

Electron microscope cross-section of a spore of Bacillus subtilis, showing the cortex and coat layers surrounding the core (dark central area). The spore is 1.2 microns across, about 100 times smaller than the width of a human hair. (Credit: S. Pankratz) |

"If we are able to discriminate between spores based on size or swelling characteristics, it's a test we could do in seconds to minutes," said Andrew J. Westphal, a research physicist at UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory.

Westphal and UC Berkeley physics professor P. Buford Price, along with microbial biologists Terrance J. Leighton and Katherine E. Wheeler of the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute, will report their findings next week in the online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The article will be posted on the Web sometime during the week of Feb. 10.

On Jan. 22, the federal government began to deploy environmental monitors to detect airborne bioterrorism agents, including anthrax and smallpox. The system relies on filtering air and sending the filters to a lab, where any attached microbes would be cultured and identified. Even with advanced techniques such as PCR (polymerase chain reaction) to detect microbial genes, the turnaround time would be 12-24 hours.

A device to scan for Bacillus spores of a certain size and swelling time could provide an answer in about 10 minutes.

"This wouldn't be a foolproof way of saying, "You've got anthrax spores,'" added Price, "but it would be a flag for you to go to the next step, perhaps a PCR test to detect anthrax DNA."

The new technique also could mark a significant advance in biological imaging.

"The technology that Price and Westphal have developed is quite extraordinary," said Leighton, an anthrax expert and UC Berkeley professor emeritus of molecular and cell biology. "There is great interest in trying to manipulate and image single microbial cells, because they are at the limit of resolution of normal optical microscopes. This technology pushes the lower limit of resolving power by perhaps a factor of 100 beyond what has been demonstrated previously, so you can see much more fine structure and gather much more information about the shape and the response of the single cell."

Price and Westphal first considered using size to discriminate between Bacillus spores, more properly called endospores, after anthrax spores began showing up in mail at spots around the East Coast. Both physicists had experience measuring microscopic objects during more than a decade spent searching for the minuscule tracks of cosmic rays in special glasses and of interplanetary dust grains in aerogels, and more recently, searching for unusual microbes in Greenland and Antarctic ice.

In researching what is known about spore size, they found that most measurements have been very rough and have not taken account of humidity or other environmental factors. The lack of data is due partly to the spores' size. With diameters of around two microns - about one-hundredth the width of a human hair - they are smaller than the resolution limit of most light microscopes, so precise measurements are not easy. More precise electron microscope images can only be taken of thin sections of spores in a vacuum, eliminating any possibility of gauging the effect of humidity.

About 10 years ago, the two developed a technique to extract more precision from optical microscope measurements. Using a microscope with attached CCD camera - a basic camcorder - Westphal takes hundreds to thousands of snapshots of an object. Each image is slightly offset from the others, allowing him to average the sizes to obtain a more precise measure of the object's size, often to within one-hundredth the width of a single pixel.

In practice, an automated microscope rapidly scans a surface, measuring and recording the size of every object and fitting it to the shape of an ellipse. The absolute precision of a single measurement is better than 50 nanometers, or just two percent of a micron. By measuring the same object multiple times, the precision can be improved by a factor of 10, to better than 5 nanometers.

"We are taking advantage of modern electronics and image processing to look at the size of individual spores with very high time resolution and rapid analysis," Westphal said.

In their first attempts, they found that the spores of four types of Bacillus differed significantly in size - enough to let them distinguish each by size alone. The four were B. cereus, which can cause food poisoning; the insecticidal B. thuringiensis; and two harmless soil bacteria, B. subtilis and B. megaterium.

To determine whether spores change size with environmental conditions, they checked the size of B. thuringiensis spores under varying levels of humidity. To their surprise, spores swelled significantly - about 4 percent - under conditions of high humidity. The swelling took place in two stages - spores swelled about 2.9 percent in less than 50 seconds, and then increased another 0.9 percent after about eight minutes.

Price and Westphal interpret this as rapid water diffusion into the spore's outer coat and cortex, followed by slower diffusion into the core. When subjected to a dry environment, the spores shrink.

The swelling with humidity may explain why spores are more susceptible to being killed by gases such as formaldehyde, ethylene oxide and chlorine dioxide in conditions of high humidity. A larger, swollen spore has larger pores to admit more gas.

"This paper provides one potential mechanism for why, with higher levels of humidity, one sees greater efficacy of spore killing," Leighton said. "That is very important for decontamination, whether it's medical instrument sterilization, building decontamination or removing toxic mold. It's a fundamentally important observation."

Price also noted that the reaction of spores to humidity could be a precursor to germination, which typically occurs in the presence of water and nutrients. By swelling, spores may be priming themselves to quickly germinate when food becomes available.

More research needs to be done before the technique can be adapted to detection and identification of species of Bacillus spores, Price emphasized. He and Westphal are planning to study the size of spores grown under different conditions and test whether spore agglomeration interferes with the measurement of individual spore size. Westphal thinks that agglomeration will not be a problem, because he was able to measure the sizes of individual spores from Mosquito Dunks, a commercial preparation of compressed B. thuringiensis spores used to control mosquito larvae.

They also plan to study defanged anthrax spores to determine whether, like the other Bacillus strains, they have a distinctive size and reaction to humidity.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.