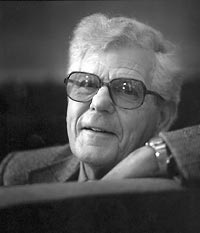

Professor emeritus and prominent international relations scholar Ernst Haas dies at 78

BERKELEY – Ernst Bernard Haas, Robson Professor of Government Emeritus in the University of California, Berkeley, political science department, died March 6 after a short illness. Haas lived in Berkeley and was 78 years old.

A prominent scholar in the fields of international relations and international organizations, Haas joined the UC Berkeley faculty in 1951. Following his retirement in June 1999, he continued in an active role as a researcher and teacher on campus.

Ernst B. Haas (Howard Gale Ford photo) |

Haas was born in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1924, and he and his family immigrated to the United States in 1938. Haas attended the University of Chicago prior to working in the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Service from 1943-46. He received his PhD in public law and government in 1952 from Columbia University, where he had also received his BS and MA. He began his academic career in 1951 at UC Berkeley, where he remained until his death. In addition, he was director of the UC Berkeley Institute for International Studies from 1969-73.

A leading authority on international relations theory, Haas was concerned with the concepts and process of international integration. He published 20 books and monographs, as well as 56 articles and book chapters. His early groundbreaking works, "The Uniting of Europe" (1958, re-issued 2003) and "Beyond the Nation-State" (1964), are still widely cited and read. The former was named by the Journal of Foreign Affairs as one of the 50 most significant books in international relations in the last century. His recent work included a two-volume, comparative historical study of nationalism, "Nationalism, Liberalism, and Progress" (1997 and 2000).

Haas was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and he served as a consultant to many bodies in academia, publishing, government and international organizations, including the U.S. Department of State, the United Nations and the Commission on Global Governance.

"He was the kind of mentor that you get once in a lifetime, and he may well have come from a school that does not produce mentors like that any more," said John Ruggie, former student and current professor of international affairs and director of the Center for Business and Government at Harvard University. "God knows where I'd be today if I hadn't met Ernie. He was much more than a professor; he was a surrogate father and a good friend."

One of Haas's oldest friends, Stanley Hoffman, a professor in the Harvard Center for European Studies, appreciated both his scholarship and sense of humor. "There was a real bond between us," he said. "We didn't always agree, but I think the disagreements nourished our friendship. He was to me a model of what a good political scientist should be. I loved his sense of humor, his irreverence, and his refusal to take the pomp and circumstance of the profession seriously. My main regret is that we lived 3,000 miles apart."

Years ago, Haas attempted to recruit Duke political science professor Robert Keohane to teach at UC Berkeley. Keohane did not accept a position, but that did not diminish his respect for Haas. "He was my mentor and exemplar of what a scholar should be. The fact that his first book, written in 1958, is still widely used is and is still a very viable theory is testament to his work. But even still, he would continue to refine and criticize his own work. He was always interested in how organizations learn and how they adapt."

Haas was teaching a course about theories in international relations this semester, and colleague Steven Weber will take over the class.

"This course has almost an iconic stature among grad students," Weber said. "It had almost a mythic stature, and I know I will not be able to fill his shoes when I take over teaching it." Weber said Haas will not only be remembered as a great teacher, but "as one of the truly great social scientists of the 20th century."

Weber related that Haas was one of the first to take seriously postwar efforts toward European integration. "He was watching and trying to understand policies surrounding something much larger than the nation-state. We take this for granted now, but when Ernie began his studies, this was groundbreaking."

Anne Clunan, who received her PhD at Berkeley in 2001, said she felt fortunate to have been his student and his teaching and research assistant. Currently an assistant professor in the Naval Postgraduate School at the Department of National Security Affairs in Monterey, Calif., Clunan said she will especially remember Haas's commitment to teaching.

"Not only was he able to expand our ability to think, he deeply cared about every lecture he gave," she said. "Every class was in some way revelatory, as Ernie would force our minds to do intellectual gymnastics we'd never done before." She also recalled how impressed she was at his depth of caring for undergraduate students. He related a story to her of how he couldn't sleep worrying about his undergraduate lecture the next day.

"You rarely find that level of concern in someone who's been teaching for one year," she said, "let alone over 40."

Haas was married to the late Hildegarde Vogel Haas for 57 years. He is survived by his son, Peter M. Haas, a professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst; his daughter-in-law, Julie Zuckman; his sister, Edith Cornfield of New York City; and a grandson.