Professor Enrico Jones, an expert in minority mental health, dies at 55

BERKELEY – Enrico Edison Jones, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, and an expert in minority mental health, died on March 29 after a three-year battle with cancer. Jones was 55 years old.

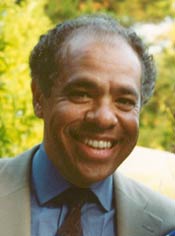

Enrico Jones |

An Oakland resident, Jones was born in Munich, Germany, where his father was stationed in the military. He spent his early years in Germany and Rochester, New York.

Jones received his undergraduate degree in general studies in 1969 at Harvard University, where he was a National Merit Scholar. He came to UC Berkeley as a graduate student in psychology and earned his Ph.D. in 1974. He received further training at the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute. In 1974, Jones joined the UC Berkeley faculty, where he was an active researcher and teacher until his death.

During his years at UC Berkeley, he was on staff at its psychology clinic and was director of the clinic and the clinical psychology training program from 1994 to 1997.

Jones was an active clinician. He maintained a practice in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy in Berkeley, and he was on the attending staff of Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco from 1976 to 1994. From 1982 to 1996, he was an associate clinical professor in UC San Francisco's Department of Psychiatry and at its Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute.

"He was one of the true clinician researchers in the sense that he used his research to guide the way he worked with his patients, and he used the way he worked with his patients to guide his research," said Dr. Stuart Ablon, assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the psychotherapy research program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Ablon was a graduate student of Jones' - the two collaborated from then until last week.

"He was an extremely thought-provoking, incredibly intelligent man who was really intrigued by human feeling, thinking and motivation," Ablon said. "Most people are interested in whether therapy works, but Enrico realized long ago that a more intriguing question is how therapy works. People have theorized about this for generations, but he was one of the first to have an empirical method that could be replicated to quantify the nature of human interaction in therapy."

With the publication of "Minority Mental Health" (Praeger Publishers, 1982), in collaboration with his UC Berkeley graduate school mentor, the late Sheldon Korchin, Jones formally assumed a major leadership role in the education and training of ethnic minority students. He inspired ethnic minority students with his enthusiasm and devotion to research as well as to academic and clinical endeavors.

His efforts to widen the pool of potential doctoral candidates on behalf of underrepresented groups led to the detection of excellence that otherwise might not have been recognized. He worked tirelessly to broaden the diversity of the psychology department at the university and to strengthen awareness of diversity's positive effects.

These efforts served the causes of academic excellence and rigor, as well as social justice, for ethnic minority students. For his efforts, in 1996 Jones was awarded the American Psychological Association's Kenneth and Mamie Clark Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Professional Development of Ethnic Minority Students.

UC Berkeley professor of psychology Rhona Weinstein came to teach at UC Berkeley a year before Jones did, and she remembered being impressed by him from the very beginning. "Thinking back to 1974, these were exceedingly difficult times for an ethnic minority scholar," she said. "But he had great dreams, and I am so pleased to see so many of his dreams realized.

"He has been able to create a cadre of students who have continued this work, and he has left a data archive for students, clinicians and researchers."

Jones's current students said they will remember him as an exceptional role model and teacher.

"As a mentor, Professor Jones blended warmth and toughness, which made him an effective advisor and collaborator," said graduate student William Lamb. "His teaching style in seminars was often informal and student-centered. And Professor Jones always made time for students. Always."

"He was so motivated by his work. He was so committed to find out what it was about psychotherapy that made it work," said second-year graduate student Tai Katzenstein. She said she will also remember his wonderful sense of humor and "the twinkle in his eye when he would lean back in his chair to make a wry comment or tell a joke."

Jones's methods of rating therapeutic process in an empirical way so it can be quantified is examined in his recent book, "Therapeutic Action: A Guide to Psychoanalytic Theory" (Jason Aronson, 2001). Peter Fonagay, Freud Memorial Professor of Psychoanalysis at the University College, London, said "the book is a masterful achievement, a genuine integration of systematic observation with the art of clinical practice. This is an invaluable book to guide all therapists, the experienced and the novice, through the troubled waters of psychodynamic treatment."

Jones was an avid reader, and he enjoyed skiing and mountaineering. He scaled Machu Picchu in Peru, Mont Blanc in the Alps and peaks in Alaska.

Jones is survived by his wife, Cheryl Goodrich of Oakland; his mother, Marta Jones of Upper Marlboro, Md.; and four sisters, Ramona Moss of St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, Cornelie Jones of Buffalo, New York, and Ricarda Jones and Manuela Ruby Jones, both of Upper Marlboro.

A memorial service will be held Friday at 1 p.m. at Chapel of the Chimes, 4499 Piedmont Ave., in Oakland. Donations in his memory may be made to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation, 3 Forest St., New Canaan, CT 06840.