|

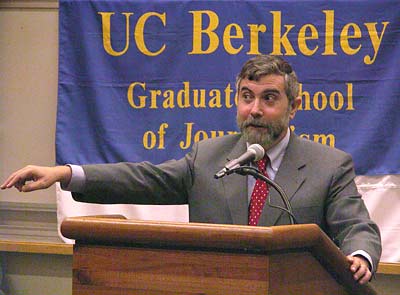

Paul Krugman illustrates what the United States economy will look like as the cartoon character Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff. (Steve McConnell photo) |

"Starving the government": Economist Paul Krugman says that's what the Bush administration's tax cuts and foreign policy have in common

BERKELEY - The Bush Administration's handling of tax cuts and the Iraq war are part of a pattern of misrepresentation and governing that deserves to be called dishonest. That's the contention of Princeton economics professor and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, who spoke on the UC Berkeley campus on Friday, September 26.

Krugman took the podium before a packed auditorium at the Haas School of Business ostensibly to lecture on "The War in Iraq and the American Economy." But as Orville Schell, dean of Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism (a cosponsor of the event), indicated in his introduction to Krugman, the economist's "interesting odyssey" from dispassionate academic to "angry liberal" originated with events that predated the war in Iraq: specifically, the tax cuts first proposed by then-Presidential candidate George W. Bush in 1999.

Krugman began with "If you follow the arc of what I've written" — and many in the audience, which included Nobel Laureates in economics George Akerlof and Daniel McFadden, have done just that — "my thinking moves from puzzlement to bemusement, then gradually to outrage. This is very upsetting stuff."

The origin of that puzzlement, he said, came during the 2000 presidential campaigns, when Bush was pushing for broad tax cuts. At that time, in the "only instance of censorship" Krugman reports experiencing at the New York Times, he was not permitted to use the word "lie" to describe the blatant contradiction he observed as an economist between who the tax cuts would most benefit - the very richest Americans - and the working-class and middle-class taxpayers that the Bush team contended would be its beneficiaries.

As Krugman has written extensively, most recently in "The Tax-Cut Con," a 7,000-word opus for the New York Times Magazine, "the tax cuts were sold under false pretenses ... The 2001 tax cut is delivering the great bulk of its benefits to the top 2 percent of the population." A full 42 percent of the tax cuts go to benefit people making more than $300,000, he said, and more than 50 million taxpayers will receive no tax cut at all.

The most disturbing element of the debate over tax cuts, said Krugman, was that "the ostensible reason for them kept on shifting." During the 2000 presidential campaign, the rationale was supposedly to "return the budget surplus to the people," but Krugman claims the hidden motive was signaling the far right of the Republican Party that Bush would be as friendly to the wealthy as then-candidate and billionaire Steve Forbes. And then along came 2001 and the stock market nosedive, and all of a sudden "tax cuts became the perfect answer to the slowdown in the economy." The latest round of tax cuts passed this year, meanwhile, were advertised as being about long-term growth and incentives.

All of the above tax-cut rationales - while creating the lion's share of the $500 billion-plus deficit the United States faces for the next fiscal year - were unlikely to inspire any of the positive economic impacts touted by the Bush administration, Krugman said. But what concerns him most is the administration's reliance on a "constantly shifting rationale for a policy that was invariate." This strategy was replicated in the war in Iraq, he argued: first the reason for declaring war was Iraq's ties to Al-Qaeda, then Saddam Hussein's possession of weapons of mass destruction, and then when those weapons proved elusive, the war was defended on humanitarian grounds - liberating the Iraqis from a tyrant.

Krugman said that he and others had at first found it hard to believe that the Bush administration would apply the same false-pretense technique used to sell the tax cuts to sell the war in Iraq. "Sure they do that on tax policy," he said he thought, "but they wouldn't do that in matters of life and death!" What he realized, however, was that George W. Bush and his advisers represent something entirely new. "Other administrations have shaved the truth, but this is different," Krugman said. The difference? Now "we're dealing with people with a radical agenda."

Krugman signs copies of his new book, "The Great Unraveling: Losing Our Way in the New Century," for a long line of audience members. |

With the government currently operating on 25 percent fewer dollars than it needs to fund all of its obligations, Krugman said, the eventual result will be the rollback of even supposedly inviolate social programs. "You can't eliminate 25 percent of spending without cuts into the big three: Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. But you can't do that. So something has to happen. Will we go bankrupt? So far the markets are in denial," he said. "There will come a moment when the bond investors will rebel. The United States is going to do a Wile E. Coyote run off a cliff, look down, and" — he made a cartoon-like face of surprise — "poof!"

Krugman believes, he says, that the radical long-term plan of the Bush administration is indeed to force a budget situation where the only choice is to slash the Big Three, thus returning the U.S. government to pre-Roosevelt days when the elderly made up a much larger percentage of the poor population, and only the rich could afford good education and had access to health care.

"K Street and Pennsylvania Avenue have merged. The lobbyists are inside the government," Krugman said. No longer is industry influence limited to large campaign donations, he alleged - industry holds positions of federal authority with direct conflicts of interest. Krugman noted that Vice President Dick Cheney will benefit in the future from the lucrative no-bid contracts that his former employer, Halliburton, has enjoyed in Iraq. However, he dismissed that instance as a minor example.

Acknowledging the controversial nature of his remarks, Krugman said he was often reminded of a comment by journalist Molly Ivins: "The thing I hate most about the Bushies is that they make me feel like a paranoid conspiracy theorist."

Ultimately, the tax cuts and the war in Iraq "should be put in context with something going very awry in the way we govern ourselves," summed up Krugman. He said he was glad that, with the growing furor around the additional $87 billion bill presented to Congress to pay for the war in Iraq, the American public appeared to be becoming alert to a "not very appetizing" pattern of events.

"It's going to be an exciting, interesting, and very unpleasant time in the couple of years ahead," he concluded.