|

Porcupine Cave discoverer Don Rasmussen and volunteers starting the generator for another day's work at the cave. (Photo by Tony Barnosky) |

Colorado cave yields million-year-old record of evolution and climate change

BERKELEY – For at least a million years, owls throughout the West have been snapping up sagebrush voles and reducing them to gray pellets of fur, bones and teeth littering the foot of the roost.

Thanks to pack rats, however, these voles have not been forgotten.

In one Colorado cave, a pack rat collection of teeth and bones has yielded a layered slice of vole history between 600,000 and a million years ago, providing an unprecedented picture of how a species changes and evolves, and how its evolution is affected by climate change.

"Everything in the cave has been nicely preserved at a controlled temperature and humidity, like putting the stuff in a refrigerator for 750,000 years," said Tony Barnosky, a University of California, Berkeley, paleobiologist.

He and his former graduate student Chris J. Bell, now associate professor of geological sciences at the University of Texas at Austin, detail their study of fossil sagebrush voles, a rat-like rodent of the arid West, in a paper published online today (Tuesday, Oct. 21) in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"This is the first study where we've actually taken a living species and looked back almost a million years at the population level to see how it changes through time," said Barnosky, an associate professor of integrative biology and associate curator at UC Berkeley's Museum of Paleontology.

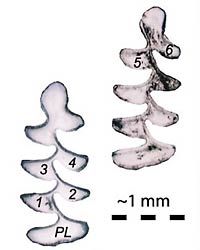

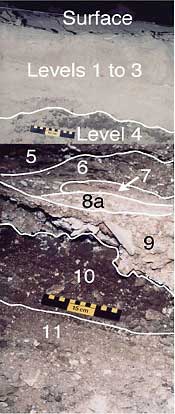

Above: The chewing surfaces of the tiny molars of the sagebrush vole, showing the slight changes in cutting surface that distinguish a million-year-old vole (left) from its evolving cousin. The vole evolved increased cutting surface presumably to let it deal with the increased grit and more abrasive substances in plants characteristic of arid conditions. Right: Layers in the Porcupine Cave "pit" from which scientists recovered vole teeth and many other vertebrae fossils dating back nearly a million years. |

Photos courtesy Tony Barnosky |

"We've got a snapshot very early in the history of the species, around 750,000 years ago in the middle Pleistocene, in which we can trace details of what happens in time, plus a snapshot at 10,000 years and a modern snapshot."

Together, these snapshots show very gradual change in the sagebrush vole, Lemmiscus curtatus, as the climate goes through one of many periodic cycles of glacial advance and retreat, with the original vole population coexisting and probably interbreeding with its evolving cousins.

However, a major climate alteration about 800,000 years ago dramatically shifted the population balance toward the evolving vole and away from the original vole population.

The original vole population still took about 800,000 years to die out, because it lived as recently as 9,500 years ago. Sediments of that age in a Nevada cave still contain the animals' fossilized teeth. In the last 10,000 years, however, the original vole has disappeared entirely, leaving the new variant that continues to evolve away from the original.

"There is debate about the role of climate change and the glacial/interglacial transitions in driving speciation, that is, the evolution of a new species," Barnosky said. "Our study suggests that species adapt to handle routine climate change, and only something out of the ordinary initiates significant evolutionary change. It takes a long time for a species to change, and even the major climatic change 800,000 years ago wasn't dramatic enough to cause the origin of a new species.

"At least for small mammals, there may not have been much speciation in response to climate change in the Pleistocene."

Though the million-year-old voles and today's sagebrush voles are distinctly different based on the shape of their teeth, they probably would be considered the same species, Barnosky and Bell concluded. They acknowledge, however, that other biologists might view the two voles coexisting some 800,000 years ago as two separate species, one of which went extinct.

"The species concept is an especially challenging problem for paleontologists, who work with only bones and teeth," Bell said. "Here we are working with fossilized remains of a species that in the modern biota only has one species, and have shown that, through time, the morphological patterns within that species have changed.

"But we think we're looking at change within a species, not necessarily a speciation event."

"This study shows that, while we can draw a firm boundary around a species we see today in the landscape, we can't draw a firm boundary around species through time - the definition gets fuzzy,"

Barnosky added. "In our study, we see species change at the population level, but not change from one species into another."

In light of the slow pace of speciation and today's rapid climate change, these findings hold a sobering lesson, Barnosky said.

"It's likely that speciation takes place over a longer time interval than extinction," Barnosky said. "So, climate changes like the global warming we are seeing today are probably happening too fast to cause anything but extinction."

The major climate shift that propelled the emerging vole population into the dominant spot 800,000 years ago was the sudden switch from a 41,000-year glacial cycle to a 100,000-year glacial cycle. This shift, caused presumably by interactions among the long-period precessions of Earth's orbital and spin axes and cyclic changes in the shape of Earth's orbit, initiated an abnormally hot and dry period evident in the cave sediments.

Barnosky has been excavating and analyzing fossils from Porcupine Cave in Colorado since 1985, when he was at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. Originally discovered in Park County in the 1860s by miners excavating a promising vein of silver, the cave had been known since then primarily to cavers and entered only through the miner's adit. That was until oil geologist Don Rasmussen and his son Larry stumbled in in 1981 and noticed the rich bone deposits in the cave.

Since then, the cave's history has been reconstructed from the sediments and the bones, which are in collections at the Carnegie Museum, the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, UC Berkeley's Museum of Paleontology and the University of Kansas Natural History Museum. The cave, located at 9,500 feet, evidently was open intermittently over a 400,000-year period starting slightly less than a million years ago, in the middle Pleistocene, an era known for its ice ages. During this period, wood rats, colloquially known as pack rats, scavenged nearby owl pellets and scat from coyotes and other mammalian carnivores to decorate their elaborate nests.

Estimates are that the small bones and teeth from the pellets and scat are a good representation of the small animal populations from about a 10-mile radius around the cave. Excavations have revealed the bones of at least 127 separate species, including birds, reptiles and 73 distinct mammals.

One of the cave's most abundant mammals was the sagebrush vole, a 3- to 4-inch rodent, excluding tail, that lived on seeds and plant material and served as a major food source for raptors and small carnivores. Because the voles were so prevalent and well represented throughout the cave sediments, especially at a site called the "pit," Barnosky and Bell hit upon them as a perfect animal to follow through time for a glimpse of evolution at work. The 400,000-year period was particularly interesting because it spanned two transitions between a glacial period, characterized by a cool, wet climate, and a drier interglacial period. The first transition was toward the end of the time characterized by 41,000-year glacial cycles, while the second was early in the series of 100,000-year cycles that persist today.

"There is a lot of controversy about how new species form," Barnosky said. "How long does it take? Is speciation something that happens when one population is isolated from other populations? Do you need a big selection event, such as climate change?

"We can address these questions because we have a really good fossil sample that lets us detail species through time and compare them with modern species."

While other scientists have studied late Pleistocene mammals, they've most commonly gone back only about 11,000 years to the beginning of the so-called Holocene, a period in which it is hard to distinguish the effects of climate change from the effects of humans, who were then roaming North America. Also, such studies sample only a small part of the typical 1.5-million-year life span of a mammalian species.

The new study from the middle Pleistocene looks for the first time at climatic effects on small mammals in the absence of humans and over a million-year time span.

Since teeth were most abundant and are often diagnostic of vole species, Barnosky and Bell extracted teeth from 10 recognizable layers of cave sediment, comparing fossils of 154 first lower molars and 57 third upper molars with 363 specimens taken from modern vole populations. The combined study of fossil collections with the modern material housed in UC Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, where Barnosky is a member of the research faculty, allowed a detailed understanding of how the populations vary through both time and space.

The chewing surface of the first lower molars is divided into various triangular extensions off the main tooth ridge, and distant ancestors of this vole had teeth with three of these triangles. The million-year-old voles from the cave came from populations with four triangles, five triangles, and an intermediate blend, probably indicating interbreeding between the two other types. Because fossils of the sagebrush vole are not found before the species appears full blown in Porcupine Cave, Barnosky thinks that the sagebrush vole had only recently evolved.

Later sediment layers showed varying proportions of four-and five-triangle teeth, with the balance tipping toward five triangles only after the major climate event 800,00 years ago. This is seen in the cave's uppermost sediments, including the top 600,000-year-old layer, in which six-triangle molars appear for the first time.

The more triangles, the greater the enameled cutting edge, which presumably would be an advantage during more arid conditions, Barnosky said. With more dust in the air and an increase in plants adapted for arid conditions, which contain more hard silica, it makes sense that evolution would select for voles with teeth that had more cutting surface that would not wear out as quickly.

Barnosky and Bell compared these older teeth with more recent vole teeth found in sediments from Snake Creek Burial Cave in Nevada, which has been dated at between 9,500 and 15,000 years ago. In this cave, both four- and five-triangle teeth were represented among the fossils, though five triangles predominated.

Today, no living sagebrush voles have teeth with four triangles. They have teeth with five, six and sometimes seven triangles, showing continued evolution toward more cutting surface. Since different species of voles differ in the number of molar triangles by about two or three, the sagebrush vole today is probably the same species as that of 800,000 years ago, though it clearly is evolving into a species more adapted to hot and dry conditions, Barnosky said.

"The pattern of increasing number of triangles is repeating itself across geographic space," Bell said. "We see it in Porcupine Cave, we see it in Cathedral Cave in Nevada, we see it in the Kennewick road cut locality in Washington. Across geographic space and at different times, we see the same trend in increasing complexity in Lemmiscus populations."

Barnosky has edited a book, to be published next year by the University of California Press, about what Porcupine Cave tells us about biodiversity and climate change.

The work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation.

The paper is available online at http://www.catchword.com/rsl/09628452/previews/contp1-1.htm