UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

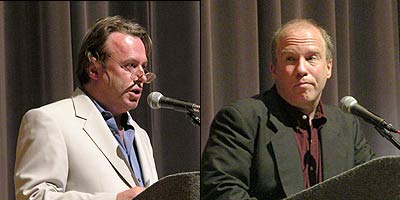

Christopher Hitchens (left) and Mark Danner (BAP photo) |

Has Bush made us safer? Journalists debate U.S. security in the aftermath of the Iraq war

Webcast: Watch

the Hitchens-Danner debate | 1:44 hour Webcast: Watch

the Hitchens-Danner debate | 1:44 hour |

BERKELEY – The question of whether President George W. Bush has made Americans safer hinges on whether the United States was justified in going to war with Saddam Hussein in the first place. That was one of the few points on which two respected journalists, Christopher Hitchens and Mark Danner, agreed in a heated debate Tuesday night.

According to Hitchens, "neutralism and nonintervention were never options available to us" when it came to war with Iraq. Nor does the violence continuing in the war's aftermath negate the importance of disarming Saddam Hussein.

Danner argued that the Bush administration launched the war with Iraq under false and misleading pretenses, and that the ongoing conflict is becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: "It was a war against terror? Now we have a situation on the ground where there are more jihadists coming over what are now essentially open borders into Iraq. Were we worried that Iraqis would be killing Americans? Well, they are doing so. Were we worried about more suicide bombings? We see it on our television screens every day."

Hitchens and Danner squared off November 5 at UC Berkeley's Wheeler Hall for the second of two intellectual jousts sponsored by the Goldman Forum on the Press & Foreign Affairs and UC Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism. The first debate, which took place January 29, essentially posed the "before" question - "Will invading Iraq make America a safer or a more dangerous place?" - while for the second, the two men were asked to consider the result of the invasion. Hitchens is a contributing editor for Vanity Fair, a former Koret Foundation Teaching Fellow at the Journalism School, and the author most recently of "A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq." A pugnacious writer unafraid to take on public figures such as Henry Kissinger or even icons such as Mother Teresa, Hitchens declared early in 2002 that he supported "regime change" in Iraq. Mark Danner, a UC Berkeley journalism professor and a staff writer for the New Yorker, has covered the costs and consequences of wars in South America, Haiti, and the Balkans in books such as "The Massacre at El Mozote." Back in January, he advocated a pragmatic path of waiting for inspections to run their course and waiting for the United Nations to reach a consensus on how to deal with Saddam Hussein.

Neither man had changed their mind much since the earlier debate. As the event moderator Orville Schell, Dean of the Journalism School, put it in his introduction, the country has found itself in a war that is more difficult than was anticipated, and Americans continue to be "polarized around what we've done and what we might have done."

For Hitchens, the path remains clear. In his opening statement, he reread a passage from "A World Transformed," by George Herbert Walker Bush and General Brent Scowcroft, that Schell had also previously cited: "Going in and occupying Iraq, thus unilaterally exceeding the United Nations' mandate, would have destroyed the precedent of international response to aggression that we hoped to establish. Had we gone the invasion route, the United States could conceivably still be an occupying power in a bitterly hostile land," Bush, Sr. and Scowcroft wrote in a passage that to many seems eerily prescient. But to Hitchens, it represents the fallacy of conventional wisdom: that the anti-Saddam war, or the "regime change" campaign, was "elective and voluntary rather than . something inescapable, ineluctable."

Hitchens argued that war was justified on humanitarian grounds, to remove a "psychopathic sadistic megalomaniacal dictator" who was terrorizing his people and posed an immediate threat to U.S. national security. "There is much to celebrate in the new Iraq," he said, listing several benefits he sees from the success of the first objective including restoration of the ecology of Iraq's southern marshes, a flowering of the Iraqi news media, the freedom to follow the majority Shiite religion, emancipation of the schools and universities, and consolidation of Kurdish autonomy. In support of the idea of Iraq posing an immediate threat, Hitchens pointed to the fact the Saddam Hussein's speeches were becoming "ever more demented and extreme and ever more Islamist in tone," that the European idea that Saddam was contained was belied by Saddam's ability to withstand sanctions and defy U.N. inspectors.

Pointing to the report on weapons of mass destruction being conducted by David Kay, the former U.N. Special Commission chief nuclear weapons inspector now heading the Iraq Survey Group for the U.S., Hitchens cited "compelling evidence of a complex concealment program, of the designing of missiles well beyond the permitted legal range, of the intimidation of scientists and witnesses, and of the incubation of deadly biological toxins" as evidence that the threat was real, and that disarming Iraq had indeed left the United States - and the world - safer.

Danner, who returned recently from a three-week trip to Iraq, disagreed unequivocally. "The president responded to the attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. by attacking Afghanistan and leaving it as insecure as he found it," he began. Meanwhile in Iraq, the incidence of attacks on U.S. soldiers rose from an average of 15 per day when he first arrived in Baghdad to 35 by the end of his trip, he said.

But the real reason that Bush has made Americans less safe, he argued, was that by falsifying or exaggerating the level of threat posed by Saddam Hussein as the main justification for going to war, the administration has essentially destroyed the credibility of one of its own strongest weapons: military intelligence. "We know much of the intelligence was - how shall we put it - crooked, exaggerated, manipulated," said Danner. "We've heard it from leaks in the administration, from within the CIA, and we've seen it with our own eyes. Donald Rumsfeld said, 'We know where these weapons are.' Condoleeza Rice said, 'This threat may become a mushroom cloud.' All of these things were false."

Danner also took issue with Hitchens's somewhat contradictory representation of Saddam's power, in which one scenario was that the dictator was getting ready to pass his oppressive torch to his two sons. The other scenario, suggested by Hitchens, argued that the Iraqi regime was weakening and was about to implode, which would have drawn in Iraq's neighbors Turkey and Iran and resulted in a situation where the U.S. also would have been forced to intervene. "I'll leave it to you to decide whether these two arguments cited in quick succession makes sense next to one another," Danner said. "Seems to me he was either getting stronger or he was getting weaker."

For his allotted five-minute rebuttal, Hitchens immediately jumped on Danner's mention of Afghanistan. "Afghanistan is less safe now than it was when the Taliban was in power and Al Qaeda was in the hinterland?" he asked scornfully, before declaring that the opposite was true, now that women were able to begin going to school and the U.S. was building safe highways from Kandahar onward.

He also pointed to the recent success of nuclear inspection teams in Iran as evidence that the war with Iraq has had positive repercussions for world security. "Does anybody believe that the mullahs' regime [in Iran] would have agreed to searches and inspections of their covert nuclear program . if the main rival of Iran had not been itself disarmed and a certain pedagogic example has been afforded them?" he threw out. The Iranians now know that if they bluff, as Saddam did, there will be serious consequences, Hitchens said.

Hitchens then excoriated Americans and by implication, the Wheeler Hall audience, for daring to view the debate's subject "from the slightly fatuous viewpoint" of a regard for one's own safety. "Yes, you are safer for the disarmament of Iraq," he said, lip curling in trademark Hitchens sneer. "Yes, you are safer, for the coming disarmament of Iran. Yes you are safer for the physical destruction of the Taliban-Bin Laden regime in Kabul. And yes you have President Bush to thank for it, and not President Clinton, and not [CIA head] George Tenet, and not the FBI. All of them allowed these developments to occur and left us defenseless in our hometowns under open skies."

Danner, a less impassioned speaker but at least on this occasion, a slightly more coherent one, continued to hammer away undaunted at what he deemed the pivotal point. "This argument is only partly to do with national security," he repeated. "It's more about national integrity . Are we citizens, or are we dupes?" - referring again to the shifting and misleading rationales given for going to war in Iraq. He pointed to Bush's recent statement that there was no evidence that Saddam was behind the September 11 attacks: it's "fascinating that he felt himself obliged to say this, because of course the administration over the course of months and months has engaged in a very clever statements, dancing around the issue . to persuade the vast majority of Americans that in fact these two threats were the same thing."

He then suggested that Hitchens agreed with the majority of Americans who continue to believe that Saddam Hussein was connected to the 9/11 attacks. Hitchens shot back that if he had believed that, he would have come out and said so, "and I still had a minute left, so I would," he joked.

Again Hitchens appealed directly to the consciences of the audience, exhorting people not to think they can watch the unfolding events in Iraq as detached observers. "There's a tendency in this discussion, one that I very much reprobate . as if to say, 'I wonder how it's going to work out. I wonder if Bush is going to win . Who is daring to look at this as if they were spectators? Who is watching this as a newsreel?" Instead, Americans should be doing more to help the people in Iraq and Kurdistan, Hitchens commanded, by volunteering for or donating to international relief efforts and nongovernmental organizations that would help Iraqi women recover and defend their new liberty, exhume mass graves, help ameliorate the damage done to the vast stretches of wetlands that Saddam Hussein first drained, then burned in an "ecological disaster that was visible from the space shuttle."

Halliburton personnel have finally contained those fires. Hitchens said any suggestion that they had done so for corporate profits was repugnant. "What must not be heard in this debate is any flippancy of that kind, any paranoid conspiracy theory garbage, or any view that we have any right to regard this struggle as if it were a matter of indifference to us, or that we are able to entertain bets on the outcome."

Danner's answer to this heated assertion was to state that now that the United States was in Iraq, there is no going back. He fully agreed with Hitchens that removing the troops was not an option and would not be for many years. Where they differed was on the importance - or not - of examining the actions and information that led to the troops being there in the first place.

"The question is whether an embrace of idealism [such as on Hitchens's part] frees us from having to look at the consequences of our actions," Danner said. "The steps between fighting a war for democracy and actually installing a democracy were not thought through. The choice is not between democracy or fascism, it's between stability and chaos."

That chaos, he argued, will not be contained in Iraq in the foreseeable future. While it rages, it has left the United States in the form of its soldiers as well as its citizens much more vulnerable to the very terrorist threats that the war was ostensibly supposed to quell, said Danner.

A question-and-answer session followed. Full recordings of this and the January debate are available for viewing at the UC Berkeley Webcast website.