UC Berkeley Press Release

|

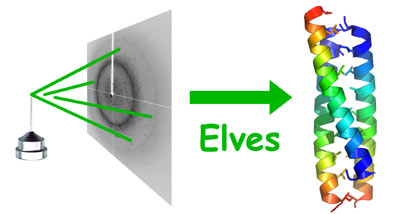

A beam of X-rays coming in from the

left hits a protein crystal and is scattered to produce a pattern of

spots called an X-ray diffraction image. In a mere 19 minutes, Elves

can convert

that image into a 3-D picture of the protein. (Credit:

James Holton/LBNL) |

Elves make protein crystallography easier

BERKELEY – Scientists are finding a computer program called Elves to be a nearly magical solution to the tedious and time-consuming task of determining the 3-D shape of proteins - a major focus of cutting-edge proteomics today - from X-ray diffraction data.

According to Elves developer James Holton, who recently received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, researchers can unleash Elves on a set of X-ray diffraction data and go on to other things - or take a nap - while the computer does the hard work and spits out a protein structure. "This is the first time anyone has reported a computer generating a protein structure by itself," he said.

"By automating X-ray crystallography, Elves dramatically speeds the process and reduces errors," added Thomas Alber, professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley. "In a recent record case, James used it to solve a new structure in 19 minutes, which is fast compared to a typical time of days to weeks."

Holton and Alber present details of Elves in a paper to be published this week in the Online Early Edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Alber is a member of the California Institute for Quantitative Biomedical Research (QB3), a cooperative effort among UC Berkeley, UC San Francisco and UC Santa Cruz to leverage strengths in the physical and biological sciences and engineering to improve human health and the environment.

Structural information about proteins is critical to understanding how proteins work, and, for drug developers, how to design drugs. Facilities like the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) make it easy and quick to obtain X-ray diffraction pictures of protein crystals.

But converting hundreds of X-ray diffraction images - each a 37 megapixel digital photo consisting of a pattern of bright spots - into a three-dimensional layout of a protein requires tweaking and twiddling programs with names like SOLVE, RESOLVE, ARP and CCP4.

"We tend to spend a lot of time running and optimizing the programs that analyze diffraction data," said Holton, who now operates an X-ray beamline devoted to protein crystallography at the Advanced Light Source (ALS). "So, I just wrote a program that does what the program manuals tell you to do to get the best solution. The surprising thing was, that works."

As a result, Elves decreases the time and training needed for researchers to interpret X-ray crystallographic data and increases the efficiency of beamlines like those at the ALS.

Holton, who copyrighted Elves through UC Berkeley, has already distributed some 100 copies of the software, and two companies licensed the software to analyze X-ray diffraction data. Now that the details are published, he plans to distribute Elves free to university and non-profit scientists.

"We love it," said Heike Krupka, a scientist working for Berkeley-based Plexxikon, a partner in the beamline that Holton operates at ALS. Plexxikon scientists use the beamline to determine how well the hundreds of drug candidates they synthesize fit into the active sites of target proteins. High throughput is needed to keep up with the pace of drug synthesis and to rapidly make improved drugs.

"Holton has made this beamline facility a 'bleeding edge' platform for X-ray technology, including Elves," Alber said.

Proteins are a main focus of research today as scientists try to make sense of the genome data now flowing out of sequencing labs around the world. Having a gene sequence, however, is far from understanding its function - for that, scientists need to know how the protein produced by the gene folds up into a compact ball, and how that ball's surface interacts with the outside world.

Drug developers, too, need 3-D structural information, not only to understand their targets but to determine how well candidate drugs interact with the targets.

For these reasons, X-ray facilities have sprung up around the country dedicated to crystallographic studies of proteins. The ALS - a particle accelerator called a synchrotron because it produces X-ray synchrotron radiation - upgraded in 2001 to become a cutting-edge source of high-energy or "hard" X-rays ideal for protein crystallography. At present, the ALS has six hard X-ray beamlines dedicated to X-ray crystallography, with two more in the works.

UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco together operate one beamline, managed by Holton, that in two years of operation has determined some 200 protein structures, 17 of which have been published. All told, only 30,000 protein structures are known out of the billions of proteins found in living organisms.

X-ray diffraction is a time-honored technique for determining the regular arrangement of atoms in a crystal. If a protein can be condensed into a solid crystal, high-energy X-rays will glance off the atoms and produce a distinctive pattern of reflections, like light shining through a faceted diamond. This pattern of bright spots is captured on film or CCD camera, so that scientists can calculate backward to reconstruct the crystal structure and thus the arrangement of atoms in the protein.

Elves is comprised of programs such as Wedger, Scaler, Phaser and Refmacer that automatically index the spots, locate heavy atoms in the protein, determine phase information through multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion, build a model, and just process the data or refine the model. No human intervention is needed as Elves tries different parameters.

"Computers are faster today and people are automating many steps in the process of analyzing X-ray diffraction data, and Elves combines all these techniques together," Holton said. "Making the crystal is 90 percent of the effort, but once you have that and you get the X-ray diffraction data, you're 19 minutes away from solving it, whereas a couple years ago it took about a year."

At the ALS, about one hour is required to collect X-ray diffraction data for a single crystal.

Elves is based on a new kind of computer interface called the conversational user interface (CUI), invented by Holton. The interface interprets English-language commands, thus allowing the user to type in simple sentences such as, "Elves, I want you to process the data in my folder." It does this by using a search engine to search free-format text input by the user and associate numbers with program variables. The program restates what it will do, setting up a conversation with the user about the process.

Unlike a standard interface, all variables that are not declared by the user are derived by the program from current information about the project. It's extremely versatile because it's not a black box, Holton said. At any stage, the user can manually direct the underlying calculation and hand the results back to the automation system for the subsequent steps. Alternatively, if the user says so, Elves can operate in total automation mode, using the derived program parameters without asking for user verification.

"The method is very cool," Alber said. "When James started the project, I didn't think it was possible. It's an amazing achievement. Elves' flexibility suggests that the CUI approach can be used to automate many other complex computerized processes."

Elves is so reliable that Holton is taking a second look at X-ray diffraction data that other scientists have given up working on. He hopes to find out what characterizes the nine out of 10 data sets that fail to produce good structural data.

"I'm going through about six terabytes of data to look for patterns," Holton said. "I think that the basic problem is the crystal. If I can find a way to reliably establish when the crystal isn't good enough, researchers can focus on making a better crystal rather than beat their heads against hopeless data."

The work was supported by a University of California Campus-Laboratory Collaboration Grant and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The ALS beamline is supported by the National Science Foundation, the University of California and Henry Wheeler.