UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

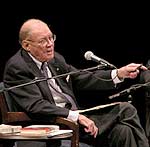

(l-r) Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara parries questions from journalism professor Mark Danner and filmmaker Errol Morris. (BAP photos) |

Robert McNamara, Errol Morris return to Berkeley to share lessons learned from "Fog of War"

BERKELEY – Near the end of "Fog of War," Errol Morris's documentary about Robert McNamara's examination of his role in the wars of the 20th century, McNamara shares his philosophy for dealing with the press. "Don't answer the question they asked," the former Secretary of Defense (1960-1968) advises with a smile. "Answer the question you wish they'd asked."

McNamara relied heavily on that strategy during a February 4 forum at UC Berkeley devoted to "The Fog of War." The question posed in various ways by Mark Danner, the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism professor who moderated the discussion with Morris and McNamara, was whether the lessons McNamara has drawn from the Vietnam War should be applied to the United States' current war in Iraq. In hundreds of prior interviews, McNamara has steadfastly refused to do so, claiming this would pose a risk to American soldiers in the field. (There is, however, an exception to that refusal, which we'll get to later.)

One of the most admired and later, the most vilified, leaders of his generation, McNamara has spent the last 20 years and three memoirs trying to navigate his personal "fog of war," the complex miasma of national decisions that resulted in the deaths of more than a million civilians in Japan and 58,000 U.S. servicemen and women (plus untold numbers of civilians) in Vietnam. In contrast to today's exhibitionist climate, where Presidential candidates, celebrities, and ordinary people seek absolution on talk shows, McNamara has never publicly apologized for either Japan or Vietnam. "At first I thought McNamara's failure to apologize was a weakness of the book [1995's "In Retrospect," which inspired "Fog of War"]; now I think that it is one of his strengths," writes Morris in his director's statement. "It is much more difficult to analyze the causes of error than apologize for it."

McNamara's perspective on his past is hard-won. And although he nimbly deflected Danner's attempts to elicit his comments on the present, it was clear that he wanted the packed Zellerbach Hall audience to learn from his mistakes — not from him. At 87, he simply belongs to a generation that equated patriotism with unquestioning loyalty to one's President and government: an idea that for younger generations has been tarnished by the Vietnam War, Watergate, the Iran-Contra affair, Monicagate, and other scandals.

Wisps of fog

Presented by the Goldman Forum on Press & Foreign Affairs and the Journalism School, the evening began with 40 minutes' worth of clips from Morris's film, currently in the running for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. The excerpts were shown in a sequence different from the movie's and failed to convey the complexity of "Fog of War," which intersperses Morris's interviews with McNamara and historical footage, stills, and recently unearthed taped conversations between McNamara and Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. The film covers McNamara's early life, touching on the four years he spent at UC Berkeley studying economics during the Great Depression, his and his wife's bout with polio, and his considerable achievements as a Harvard professor, one of the Ford Motors' Whiz Kids, and then the company's first president from outside the Ford family.

But the bulk of "Fog of War" is devoted to the parts McNamara played in the 1945 firebombing of Japan during World War II, when he was a Statistical Control Officer and a captain in the U.S. Air Force; as Kennedy's Secretary of Defense during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis; and the escalation of the Vietnam War from 1963 to 1968, when he either resigned or was fired - he maintains he doesn't know exactly which - from Johnson's Cabinet.

Errol Morris dropped out of UC Berkeley's doctorate program in philosophy to move to Wisconsin and study grave-robber-turned-murderer Ed Gein. Morris's first film was 1978's "Gates of Heaven," about a pet cemetery in Napa. |

The subtitle of "The Fog of War" is "Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert McNamara," and the film is punctuated with short statements that Morris drew from his interviews with McNamara. For example, "Rule No. 1: Empathize with your enemy," refers to McNamara's belief that Kennedy averted nuclear war by understanding what kind of a deal would allow Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev to save face, while No. 7, "Belief and seeing are both often wrong," is illustrated by a North Vietnamese attack on a U.S. warship that never actually happened - but the military so believed in it that it led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, in which Congress gave Johnson full power to wage war on Vietnam.

History is written by the winners

Another, "Proportionality should be a guideline in war," which was among the segments shown on Wednesday night, refers to McNamara's role, with General Curtis LeMay, in the 1945 firebombings of 67 Japanese cities - before the bombs were ever dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. McNamara wrote the report on the inefficiency of conventional bombing campaigns that may have inspired LeMay to take his B-29 bombers down to under 5,000 feet and rain fire on cities built of wood, killing nearly 1 million Japanese. In the film, McNamara says, "In a single night we burned to death 100,000 civilians - men, women, and children — in Tokyo. I was part of a mechanism that in a sense recommended it." He goes on to recount how LeMay admitted, "'If we lost the war, we'd all be prosecuted as war criminals.' He - and I - were behaving as war criminals . What makes it immoral if you lose but not if you win?"

Such hard questions and observations - about the importance of empathizing with the enemy, about governments seeing what they want to believe, the ethical justification for "preventive" war - fairly beg to be applied to current events, or so suggested the forum's participants. UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert M. Berdahl, in his introduction of the event, quoted Morris as saying "I don't think that Iraq is exactly like Vietnam; I don't think history exactly repeats itself. But I do think many of the mistakes we made in Vietnam are all too relevant to the mistakes we are making today." Journalism School Dean Orville Schell agreed: "I think what makes everybody so interested in the subject of Errol Morris's truly great film is the resonance that it has with the war that we are currently in now."

Morris is happy to acknowledge the echoes, but McNamara will not give them voice.

The question that McNamara wanted to answer - and returned to over and over - was not what he could do to shed insight on the U.S. war with Iraq, but what the audience and Americans citizens could do for their country's future. "We human beings killed 160 million other human beings in the 20th century," he fairly shouted, jabbing his finger at Danner as aggressively as he does at the camera in the film. "Is that what we want in this century? I don't think so!"

Preventive war - an oxymoron

Morris, who left most of the talking to McNamara and Danner, echoed that sentiment. Referring to McNamara's earliest memory - as a two-year-old watching San Francisco celebrate Armistice Day and the end of "the war to end all wars" - Morris said, "Ironic, yes, because the end of WW I ushered in a century of the worst carnage in human history . I am constantly reminded that war doesn't end war. I think there are several examples of this in the past," he added dryly. "The 'preventive war' itself is an oxymoron, and we're starting out the 21st century much as we did the century before. This to me does not augur well."

McNamara cut him off, addressing the audience fervently: "But, but, don't give up! I mean it! Don't give up! You individuals can do something about it!" He enumerated the ways: by pushing for the U.S. to develop a judicial system that governs the behavior of war (an easy way: participate in the rest of the world's International Criminal Tribunal system), by forcing Congress to debate publicly the nation's nuclear policy ("you'd be shocked if you knew what it was," he warned), and by raising not only the country's standard of living through national health care and better education, but the state of California's.

The author of a book on Haiti's war and a staff writer for The New Yorker, Danner has reported recently from Iraq and has sharpened his talons in two public debates about the war with writer Christopher Hitchens. To McNamara, he compared the Johnson administration's secretive behavior during Vietnam - about the scale, length, and cost of the war - with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld's and the Bush administration's approach to the war with Iraq. Faced with this historical duplicate of duplicity, Danner pressed McNamara to answer his question, not the one that McNamara kept answering.

"What I'm pushing you on," said Danner, "is not simply 'We can do better, we have to work for a better world.'" If McNamara has devoted the last 20 years of his life to "the notion that things can change, that lessons can be learned," he asked, what happens when we appear to have "a world where lessons haven't been learned, where in fact we seem to be in precisely the same world all over again?"

'You've got to be very careful. You have a responsibility to the people whose lives are at risk. And that's true today in Iraq, and it was true in Vietnam.' -Robert McNamara |

"Most Cabinet officers, from the past until today, believe they're there to represent the interests of the department - Agriculture represents farmers, Defense represents the military. Not at all!" McNamara answered (sort of). "Each of those secretaries represents the president! The president was elected, he had a platform." Although he would not criticize the Bush administration directly, he took a veiled swipe at Secretary of State Colin Powell for Powell's recent admission that he might have felt differently about the war in Iraq had he known no weapons of mass destruction would be found. "I don't believe any secretary should continue beyond the point where he feels he's being effective in pursuing both the president's programs and [if they are] different from what he believes, is being effective in helping the president change his program to what he believes is right," McNamara said.

McNamara's tenure at Defense ended shortly after he hand-delivered a memo to Johnson outlining his serious doubts about the continued escalation of the Vietnam War. Asked why he refused to share those doubts with the American public, even after leaving the government, for the war's remaining duration, McNamara was unapologetic. "You have to ask yourself, if you have tens of thousands of American lives at risk, whether it's in Iraq or Vietnam, if a senior official of the government says the government's policies are wrong, are you endangering those individuals?" he emphasized. "And the answer is bound to be, Yes! You've got to be very careful. You have a responsibility to the people whose lives are at risk. And that's true today in Iraq, and it was true in Vietnam."

The Globe comes knocking

Danner said that up until that day, he had "grudgingly accepted" McNamara's refusal to weigh in on Iraq, even after beseeching calls from scores of reporters. Then he pounced, brandishing a printout of a January 24, 2004, interview with McNamara by the Toronto Globe and Mail in which McNamara directly criticized the Bush administration. "If 171 [journalists] asked you, clearly one asked you in a way that brought forth a bounty of opinion," Danner scolded, reading quotations from McNamara such as "We're misusing our influence . It's just wrong what we're doing. It's morally wrong, it's politically wrong, it's economically wrong" and "There have been times in the last year when I was just utterly disgusted by our position, the United States' position vis-à-vis the other nations of the world."

After Danner finished reading, Morris turned to McNamara and said quietly, "I applaud you for saying those things."

McNamara, who perhaps has never used Google, sputtered that he didn't think that anyone would actually see the Canadian newspaper article, but he acknowledged that all of its quotations were accurate. While urging the audience to engage in public debate about the war with Iraq, he once again refused to lead it.

Robert McNamara's 11 lessons from Vietnam –Globe and Mail, Jan. 24, 2004 |

McNamara seemed almost persuaded. After a few boasts about the book's popularity on the best-seller lists and in history classes, he said, "I'm not suggesting you buy it - but the lessons are in there . I put them forward not because of Vietnam, I put them forward because of the future." Almost, that is. "Now what you want me to do is apply them to Bush. I'm not going to do it! You apply them to Bush!" he admonished.

There was time for only one written question from the audience: whether the events of September 11 had, as the Bush administration said, "changed everything." McNamara disagreed, arguing that 9/11 simply further highlighted the importance of empathizing with the enemy. "If you don't have any other weapon you're going to use terrorism," he argued. "9/11 should have taught us to be more sensitive to Muslim and Israel-Palestine problems."

Danner used the audience question as his springboard for a final tilt at McNamara, but the former Secretary of Defense had packed up his notes and books even before Danner finished talking.

"As I told you, I am not going to comment on President Bush," McNamara said, patting his briefcase. "I refer you again to the 11 principles. You apply them! .You don't need me to point out the target. You're smart enough!"

More information

• "A

Life in Public Service: Conversation with Robert McNamara," UC Berkeley

Institute of International Studies' Conversations With History series, April

1996

• "Oldest

Living Whiz Kid Tells All," New York Times, January 25, 2004

• Errol

Morris's website