UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

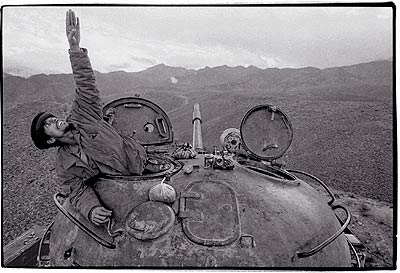

Photo by James Nachtwey. An exhibit of photos that the award-winning Nachtwey shot in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars will open March 18 at North Gate Hall as part of the conference. |

Reporters, commentators visit Berkeley to conduct in-depth postmortem of Iraq war coverage

BERKELEY – The U.S. invasion of Iraq was without a doubt the most widely and closely reported war in military history. At the start of the war last March, as many as 775 reporters and photographers were traveling as "embedded journalists" with U.S. forces, with hundreds more taking their chances outside the Humvees. The availability of cheap, portable technology such as digital video cameras and teleconferencing equipment made coverage of this war ever more immediate and intimate, giving the impression that events were being recorded in real time exactly as they happened.

But how did living and eating under fire with U.S. troops influence reporters? Did journalists ask enough hard questions about the existence of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in Iraq? And most importantly, were their stories accurate? These questions and others are the central topics of UC Berkeley's conference "The Media At War: The U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Iraq," which begins tomorrow (March 16) and runs through Thursday.

A large cast of prominent journalists will participate in the conference, which is sponsored by the Graduate School of Journalism, the Human Rights Center, the Office of the Chancellor, and several other media and philanthropic groups. With a few exceptions, the panels are free and open to the public; see the conference website for a full schedule.

"We thought it was really important to conduct a postmortem on how the media did," says Orville Schell, Dean of the Journalism School. In magazine publishing, a "postmortem" refers to an in-house review of the design, content, and timeliness of a finished issue; the "Media At War" conference will tackle coverage of the Iraq war in a more probing manner, evaluating not only the quality of reporting but also the effects of intangible pressures such as patriotism.

Schell and Eric Stover, a war-crimes investigator and director of the Human Rights Center, began planning the conference last year. "Both of us have some collective experience covering wars - I started in the Indochina war - and we know something of the fever that comes over people as a country prepares for war or is at war. That climate creates a very different field of gravity in which journalists must operate," Schell explains.

Stover was in northern Iraq last March as one of only two human-rights investigators present in the country when the U.S. invaded (see "Lifting the Fog of War: Human Rights Center Director Eric Stover reports on chaos and lawlessness in Iraq," NewsCenter, April 29). He recently returned from another trip to the country, where he was looking for mass graves and assessing the status of documentary evidence to be used in subsequent war-crimes trials. The Human Rights Center is cosponsoring the Media At War conference because human-rights reporting is very similar to journalism, he says, in that it is about "getting the facts right - who, what, when, where, and why - although you're assembling these facts primarily as an advocate for the victims and their families."

Taking part in the ambitious conference are representatives from all the major U.S. print, radio, and TV outlets, among them the New York Times, L.A. Times, National Public Radio, CNN, CBS, and ABC, along with their counterparts in European and Middle Eastern media. Although organizers Stover and Schell repeatedly invited conservative outlets such as Fox News to participate, all declined to send any representatives.

In addition to the journalists, a wide range of non-media commentators - diplomats such as former U.S. ambassador Joe Wilson, former United Nations weapons inspector Hans Blix, U.S. military spokespersons, human rights investigators, and academics from the fields of psychiatry and public health - will lend their expertise to the postmortem.

The panel topics are arranged around issues that Stover and Schell saw arise for the first time in the Iraq war. The first issue is embedded reporting. Journalists traveling cheek-by-jowl with troops is not a new phenomenon, according to Stover - the practice dates back to ancient wars and was also present in World War II - but never before have reporters taken part in the assault on a major city like Baghdad from inside military vehicles. In addition to ethical questions such as journalists' pointing out targets they see to military personnel, conference participants will discuss the psychological pressures of embeddedness and where patriotism ends - or should end - and the independence of the press begins.

"Embedded reporting is a good idea, but it shouldn't be the only food item on the menu," says Schell. "Getting coverage only from embedded reporters is like looking only into a microscope. What we need is something of the broader picture, and the chance to know other aspects of the whole enterprise." Schell will chair a panel discussion, which will include representatives from ABC Nightline and CBS's 60 Minutes, that will look at how well the broadcast news industry has performed in giving the world that broader picture. He has been openly critical of what he sees as the "one-dimensionality" of most broadcast news coverage.

The Iraq war marks the first time that U.S. journalists have had to cover their country as an occupying power since the adoption of the Geneva Conventions of 1949. In Vietnam, U.S. troops fought alongside South Vietnamese forces, while in Bosnia there was a U.N. presence, so the United States wasn't technically an occupying power under the Geneva Convention. "When your country is the occupying power, there are different questions that arise regarding covering the war and the government," argues Stover. One of the conference's panels will examine whether U.S. reporters have been sufficiently skeptical and critical, taking up the question "Is the U.S. Media Serving the American Public?"

The conference will not be confined to a U.S.-centric focus. Two sessions will present the pressures bearing down on reporters from the BBC, La Republica, Le Monde, Al Jazeera, Al Ahram Weekly, and others, and the radically different perspectives they brought to covering the war and the threat posed by Saddam Hussein's alleged weapons of mass destruction.

One of the mostly hotly anticipated segments of the conference begins at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 17, when CNN reporter Christiane Amanpour interviews Hans Blix about his hunt for those WMDs and whether his team of U.N. inspectors was pressured to inflate their reports.

"We are now beginning to understand that the weapons inspectors did a pretty good job of establishing the fact that there were probably no WMDs in Iraq. But at the time, they received nothing but utter and total contempt for their work," says Schell. "It seems that much of the best intelligence came from Blix's team in the last month before the war, while the U.S. military relied far too heavily on deluded and removed exiles as sources. I'd like to see a postmortem about the efficacy of multilateral inspectors in this situation."

The conference's final panel discussion will ask the essential question of whether the media "got it right" in its coverage of the war: did it do a fair and accurate job of presenting the factors that led up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the events that occurred during it.

"We felt that we must make time to gather everyone together to talk not only about how we handled this, but how we will handle the ongoing occupation and future trials of Saddam and his henchmen," Stover explains. "We're concerned about how much the press knows about international humanitarian law and how these courts operate. And there will be numerous human-rights issues that will emerge, such as the rights of women in Iraq and the treatment of people who are detained by the Iraqis under the new regime. The one thing we know is that there's a long row to hoe toward recovering security and stability. The press needs to be vigilant and not abandon coverage once sovereignty is returned to the Iraqis."