UC Berkeley Press Release

Researchers find no safe place to sit in California tick-infested forest

BERKELEY – After a long hike through some of California's forests, it may be tempting to rest on a log or lean against a tree. Wrong move, say researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, who found that such activities may increase the risk of acquiring ticks harboring the Lyme disease bacterium.

UC Berkeley researcher Denise Steinlein demonstrates the three actions found to be riskiest for acquiring the western black-legged tick: leaning against a tree, carrying wood and sitting on a log. (Photos by Robert Lane) |

"We sat on logs for only five minutes at a time, and in 30 percent of the cases, it resulted in exposure to ticks," said Robert Lane, professor in the Division of Insect Biology at UC Berkeley's College of Natural Resources and lead investigator of the study. "It didn't matter if we sat on moss or the bare surface; the ticks were all over the log surface. The next riskiest behavior was gathering wood, followed by sitting against trees, which resulted in tick exposure 23 and 17 percent of the time, respectively."

The study, published in the current issue of the Journal of Medical Entomology, is the first quantitative analysis of human behaviors that may increase the risk of tick exposure in California's hardwood forests. The paper has come just weeks before the start of northwestern California's nymphal tick season, which begins in early spring and continues into summer.

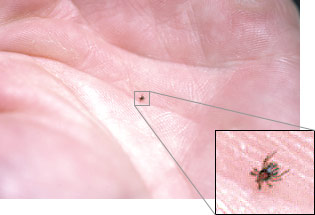

Once on a person, the nymph of the western black-legged tick (shown enlarged in inset) is readily overlooked because of its minute size. Print-quality image available for download |

The western black-legged tick, found primarily in the far western United States as well as in British Columbia, is the primary carrier of the corkscrew-shaped spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium named after its discoverer, Dr. Willy Burgdorfer. B. burgdorferi is responsible for Lyme disease, which can lead to debilitating symptoms in humans. Most human cases of Lyme disease in northwestern California appears to be transmitted by young nymphal ticks, which are notoriously difficult to detect because they are as small as poppy seeds.

Lane and study co-author Denise Steinlein, a UC Berkeley graduate student in insect biology, trekked through a hardwood forest at the UC Hopland Research and Extension Center in southeastern Mendocino County to conduct the field trials. The area, dominated by California black oak, is endemic for Lyme disease.

Jeomhee Mun, a UC Berkeley research specialist in insect biology, is another co-author of the paper.

Lane and Steinlein conducted the experiments on two back-to-back days in three consecutive weeks in 2002 between late May and mid-June. Decked out in white clothing from top to bottom, with pant legs tucked into white socks and seams sealed with duct tape, the researchers set out to learn how people might acquire nymphal ticks.

"If we're going to develop effective strategies and educational programs for the prevention of Lyme disease, it is critical that we understand how people are exposed to the ticks that transmit the bacteria in the first place," said Lane. "We intentionally looked at behaviors that people would typically engage in while spending time in the woods."

The researchers sat on logs, sat against trees, gathered wood, walked through leaves, sat still on leaf litter and sat and stirred up leaf litter for set amounts of time. Lane noted that turkey hunters can easily spend up to an hour or longer sitting with their backs against trees while trying to call in toms during the spring hunting season.

After each activity, in scenes strikingly reminiscent of primate grooming behavior, the researchers meticulously picked off and counted the ticks on their clothing and bodies. They also used an adhesive lint roller to pick up ticks that might otherwise have escaped their attention. All told, they found a total of 86 nymphal ticks on their bodies during the field trials.

"Activities that were riskiest involved considerable contact with wood," said Steinlein. "Of the six behaviors we analyzed, sitting still on leaf litter was the least riskiest behavior, resulting in tick exposure only eight percent of the time."

Why the difference between wood products and leaf litter? The clue may be in an important animal host for the larvae and nymphs of the western black-legged tick.

"The western fence lizard is an important host for the ticks, and the lizards often use logs in sunlit areas as basking sites," said Lane. "Nymphal ticks that are seeking hosts to feed upon may be going to the place where they'll have the greatest chance of finding a lizard. Humans or pets that happen to come along for a picnic lunch or a short rest on a log may be putting themselves in harm's way."

DNA tests revealed that 3 to 4 percent of the ticks the researchers found on their bodies, as well as through drag sampling leaf litter with a white flannel cloth, tested positive for B. burgdorferi and another, less prevalent human disease-causing bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Estimates from prior studies of ticks infected with B. burgdorferi in Mendocino County are higher, ranging from 5 to 10 percent on average, with some spots occasionally yielding rates of 15 percent or higher.

Tick infection rates normally are significantly higher in the northeastern and upper midwestern United States, where most cases of Lyme disease occur. Lane cautioned that the findings in this study are not intended to be applicable to forested areas in other regions of the country.

But for people frequenting areas of California where Lyme disease is endemic, the researchers recommend precautions to prevent tick exposure.

"I would avoid prolonged contact with wood as well as with leaf-litter areas, and I would strongly suggest that people inspect themselves carefully after spending time in tick-infested areas," said Lane. "Moreover, I would advise people to continue checking their skin for two to three days after the potential exposure. Nymphal ticks are so hard to see in the beginning - probably less than one in three people bitten by nymphs ever discovers the tick that bit them. But they become easier to detect once they start swelling up a bit after they've had a blood meal.

"Animal studies suggest that it usually takes longer than one day after the tick becomes attached for the bacteria to be transmitted to the host, so the sooner the tick is found and removed, the better," said Lane.

The National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention helped support this research.