UC Berkeley Press Release

|

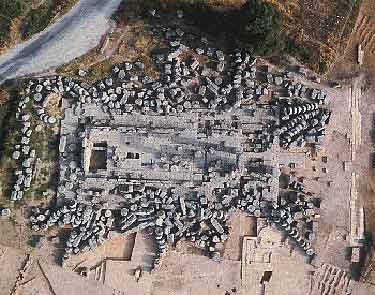

Aerial view of the Temple of Zeus in Ancient Nemea, built in 330 B.C. The column drums, averaging 2.5 tons each, can be seen scattered around the temple. UC Berkeley researchers are leading the effort to reconstruct the temple's columns. Photo courtesy of Nemea Excavations Archive, UC Berkeley |

UC Berkeley researchers lead reconstruction of Temple of Zeus in tribute to New Nemean Games

Slide

show : This year's running of the New Nemean

Games Slide

show : This year's running of the New Nemean

Games |

BERKELEY – As more than 700

runners from around the world competed in Greece last weekend

on a clay track steeped in antiquity, the Temple of Zeus stood

watch from the same place it did when athletes raced at the stadium

2,300 years ago.

Located some 400 meters from the track, the temple played a key

role in the ancient Panhellenic Games — which gave rise

to today’s Olympic Games — as the place where athletes

honored their supreme Greek god with religious rites before competition.

"The games were not just an athletic event, they were a religious festival," said Stephen Miller, professor of classics at the University of California, Berkeley. "In some sense, the athlete was dedicating himself to Zeus during the games." But unlike the temple of old, surrounded by 32 limestone columns, the temple today features just three columns that never fell down.

The Temple of Zeus, built in 330 B.C., is the site where athletes once worshipped in Ancient Nemea. The temple was originally surrounded by 32 columns, but only three survived over the millennia. UC Berkeley researchers led the reconstruction of two columns, shown here in the foreground, so that five columns now stand. This photo was taken in 2002. (Photo courtesy of Nemea Excavations Archive, UC Berkeley) |

In 2002, with the permission of the Greek government, two more columns were re-erected. Nicos Makris, a UC Berkeley professor of structural engineering, joined the project that year to begin research on the reconstruction of four additional columns.

"We hope to save more columns, but it is slow, painstaking work," said Makris, who will succeed Miller in directing the temple reconstruction after Miller retires in December. "It’s also expensive. It costs a quarter-million dollars to reconstruct one column together with its corresponding base, and we are mostly relying on the support of private donations to do this."

The temple project is part of a larger, ongoing effort that Miller began more than 30 years ago in Ancient Nemea, a tiny Greek town where he has unearthed the athletic stadium, entrance tunnel, track, bathhouse, and what is likely the world’s oldest athletic locker room.

Ancient Nemea, one of four sites of the original Panhellenic Games, is 80 miles from Athens, where the 2004 Summer Olympic Games will begin on Aug. 13.

Miller helped establish the New Nemean Games, held at the track every four years on the same cycle as the Olympic Games. The Nemean Games were first held in 1996 to revive the ancient footraces. The third such event was held Saturday, with the modern-day competitors running barefoot and dressed in tunics.

Miller said his work in Ancient Nemea wouldn’t be complete without the temple, which has not only provided links to the site’s sacred and cultural origins, but also valuable insights into innovative engineering techniques of the time.

Reconstructing it is not "an act of necessity, nor is its reconstruction forced upon us today," said Miller. "The ancient Greeks and we share a fundamental creativity that marks the human spirit at its best; we share an impulse toward a higher civilization that leaves a record of human accomplishment, and that serves as a beacon to future generations."

The 9,240-square-foot temple was built in 330 B.C. It had been assumed that earthquakes — the region is plagued with as many fault lines and temblors as California — were to blame for the fallen columns surrounding the temple.

But further investigation revealed that a basilica south of the temple had been constructed largely of material taken from the Temple of Zeus. Around 435 A.D., early Christians under the reign of Theodosios II had almost certainly demolished the 42-foot columns surrounding the temple to gain access to the interior square blocks and other material, according to Makris and Miller.

Unlike the monolithic columns of earlier Greek temples, the columns of the Temple of Zeus were each made up of 13 separate stones, called drums. The multi-drum column was typical of the Greek classical-style architecture of that era.

Each drum measured an average of 1.5 meters in diameter and 1 meter in height. Their large weight — each drum averaged 2.5 tons — probably saved them from being looted, the researchers said, as did the huge cylinders’ awkward shape, which was not conducive to building walls.

Because the interior of the temple had been robbed of so much building material, fully reconstructing the monument may not be possible. But the effort to re-erect the exterior columns continues. The first steps were taken in the early 1980s with Frederick Cooper, professor of architecture at the University of Minnesota, leading a team that catalogued 1,100 stone blocks scattered on the ground around the temple.

Once the researchers had the blueprint of where each drum should go, they set about the task of actually fitting them together. But replicating the precision of the ancient Greeks would prove to be an arduous and daunting task.

"Ancient Greek architects are known for being obsessed with perfectly fitting stones, positioning pieces together to within 1/32 of an inch," said Makris.

Miller noted that the switch to a multi-drum column design had long been considered a cost-saving measure, with the rationale that working with many smaller blocks was cheaper than dealing with a massive, single stone.

But the researchers found the preparation of two joint contact surfaces to be very time-consuming and expensive. Makris tested the stability of different column designs at his UC Berkeley lab and found a more compelling reason for the switch to the multi-drum design: seismic safety.

"The use of interlocking stones dissipates a lot of energy," said Makris. "A single stone or stones connected with mortar or cement would be rigid and less able to effectively absorb the energy induced by earthquakes."

A further linguistic clue supports the seismic stability theory:

The word the ancient Greeks used for the column drum, spondylos,

also means vertebra. The temple columns were abiding by the same

shock-absorbing principles as the human spinal column.

Indeed, the three temple columns that had not been torn down by

human hands have withstood numerous earthquakes over the past

23 centuries, including a massive 7.3 quake in 1861.

The mastery of fitting stones together leads to questions about the types of tools ancient Greek builders had, about what techniques they used to treat metals, and how they were able to achieve accuracy down to a fraction of a millimeter, said Makris.

He also added that the original craftsmen were working with limestone, a more fragile stone than marble, but locally abundant. "Building something good with poorer material is actually more challenging than building with the superior stone," he noted. "It has enormous merit that these people were able to build such a huge monument with less noble material."

With two columns reconstructed to join the three existing ones, work is now underway to reconstruct four more columns to fill out the northeast corner of the temple.

Miller says they are using as much of the original stone as possible for reconstruction, but where the original material is badly eroded, new stone must be used.

Why go to so much effort to reconstruct the temple columns?

The researchers point out that re-erecting the columns may save them from further decay. The exposed surfaces of the large, fallen drums have suffered badly from the effects of sun, moisture and weeds. In contrast, the three columns that had remained intact have weathered the years comparatively well.

"Reconstructing the columns are the best way of preserving the ancient material," said Makris.

Additional information: