UC Berkeley Web Feature

Ehren Tool as a U.S. Marine recruit in 1989, a Desert Storm M.P. in 1991, and a Berkeley graduate student in art practice in 2004. |

From jarhead to bowl maker: Grad student Ehren Tool's art of war

Flash

slide show: View a selection of Tool's work Flash

slide show: View a selection of Tool's work |

BERKELEY – "Anyone who begins a life in the arts doesn't do it for the notion of money," says Michelle Lopez, UC Berkeley sculpture professor, when asked about her student Ehren Tool's future prospects. "They do it because they don't have a choice: they have something they need to say. Ehren is one of those people."

Tool, a Gulf War veteran, does indeed have something to say: Although the U.S. may wage its wars far away, each one of its citizens is still complicit in their horrors.

Now a UC Berkeley graduate student in art practice, Tool is a former U.S. Marine who served in Desert Shield and Desert Storm in 1991. He wears his gold Marine Corps pin on a desert camouflage apron, and his hair as short as in his jarhead days. At 6' 2" and 320 pounds, he looks like a saner version of the Vincent D'Onofrio character from "Full Metal Jacket" — like someone you would not want to mess with.

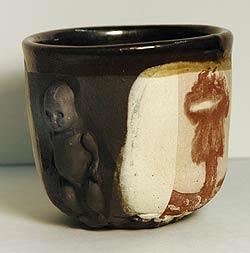

Which would be too bad, because then you'd miss out on getting one of the cups he makes. They are clay, usually dull black with a shinier black glaze, and decorated with press molds of military medals, bombs, or babies, their bottom edges scalloped into sandbags. Tool has given away more than 4,000 of them since he graduated from the University of Southern California in 2000. Homeless people have Tool's cups, as do workers at Café Strada, where he likes to mainline espresso. He mails them, free of charge, to Marines related to people he meets. More than 800 of his cups went home with people from the Burning Man festival in 2003.

One of two cups Tool gave to the writer at the beginning of this interview. (BAP photo) |

As with Tool's other work, his purpose is to make people think about war. More than a decade has passed since he served in Desert Storm — as a lance corporal with the Military Police Company Headquarters Battalion First Marine Division, in the sand near the Kuwaiti oil fires - yet he can think of nothing else.

Tool struggles to explain how his work is not antiwar — he sees that term as disrespecting the troops, his brothers — but about raising general awareness of war. "It's this freaky thing. To me, it's like there's a siren going off in the background all the time," he says. "There are so many veterans and refugees who've seen war firsthand, but then they don't talk about it when they get back to the States. So what regular people know about war tends to come from toys and pornography and video games. I give away the cups because, it's like, 'Drink out of the cup with skulls on it. Drink out of the cup with bombs on it.' We don't have money for schools, we don't have money to make the corrections system a corrections system instead of a penal system, for any of that. But we do have money for million-dollar Tomahawk missiles and $13,000 cluster bombs. And every single one of us is part of that system whether we act like we know it or not."

Third-generation soldier

W.A. Ehren Tool was born in Charleston, South Carolina, but grew up in Los Angeles. His father served in the U.S. Army and fought in Vietnam, while his maternal grandfather, a Marine, was in World War II. Despite his military lineage, Tool was planning to be a policeman when he graduated from high school, seeing that as a natural segue from volunteer work he'd done with homeless youth shelters. "But you had to be 21 to be a cop, so when a Marine Corps recruiter called me senior year of high school, I went into the Marines instead," he explains.

It was 1989, the year the Berlin Wall came down. Tool thought it was the dawn of a new era: "I totally bought it. I thought we had won the Cold War, and America was going to stop having all these shady relations with [messed]-up countries." (Tool cusses casually and often, like a soldier; his quotations have been sanitized.)

In August 1990, months after Tool enlisted, Saddam Hussein and more than a million Iraqi soldiers invaded Kuwait. Tool was one of the 500,000 troops that the United States sent in 1991 to force him back.

"When the first bombs started dropping on their side and not ours, a cheer went up. We were so anxious and stressed out, that when the war finally kicked off we sort of relaxed," Tool recalls. "But then a little bit later, you start thinking, 'OK, so we're just hitting military targets and all,' but then it's like - 'Ooh. I'm a military target. And someone would be sad if I died.' There comes a point when you have to think about the other side."

While Tool saw a lot of action in Kuwait, he was lucky enough to be able to avoid seeing much horror up close. His father wrote him letters in which he talked about his service in Vietnam for the first time. "He said if you can avoid looking at it, avoid looking at it. Because once you do, it's there in your head forever," Tool says. "So at some point there were these guys in trenches who had been blown apart, and everybody wanted to go look. And I was like, 'OK, I'll just hang out right here and watch your [stuff] for you. Go right ahead.' Everybody thought I was a sissy. But at least I don't have that memory, of the smell or whatever."

After his seven months in the Gulf were over, Tool applied for and was accepted for a special assignment as a U.S. Embassy Guard in Paris and Rome - "real hardship posts," he laughs. He explains he was choosing to defend the diplomatic side of U.S. foreign policy, rather than the military aspect. When he got out of the Corps in 1994, he enrolled at Pasadena City College on the G.I. Bill intending to become an emergency medical technician. Then he snapped his ankle, and the drawing and painting classes he was taking started looking more attractive. "The plan after the Marine Corps was to find something I like to do," Tool shrugs. "The theory was, because I like to do it, I'll do it well. Because I do it well, someone will pay me." He chuckles. "That 'pay me' thing has been tricky."

That could be because Tool is loathe to charge money for his art work. He says he can't put a price on things that to him, symbolize the preciousness - and expendability - of soldiers' lives. He had a show in Los Angeles in 2001 that happened to open the month after the September 11 attacks, when suddenly his work about the 1991 Gulf War seemed fresh and relevant. "I sold one of the seven things I had for sale, but I gave away 750 cups total for that show," he admits. At the opening, someone knocked over the object that had sold and the gallery had to give the buyer her money back.

"My business strategy may be a little off," says Tool, before resorting to his favorite all-purpose word. "Whatever."

'Bombs away! Recommended for ages 10 and up'

Although he has made more of them than anything else, Tool's work should not be judged solely by those rough mugs. He also makes more polished, beautiful bowls guarded by toylike soldiers; trophies with figures missing arms and/or legs; Tarot card parodies with illustrations scanned from Marine Corps manuals; massive installations, such as "Cluster Bombs on the Black Rock Desert" for Burning Man and this year's "393"; and conceptual pieces such as the "Letter" project. (View a slide show of these and other pieces.)

'Once a person has witnessed a war, they are forever changed.' -Ehren Tool |

With "Cluster Bombs," he (and Burning Man helpers) scattered 808 ceramic cups on a 200-by-1,600-meter area replicating the area covered by an F-16's typical payload of four cluster bombs. Each CBU-87 bomb disperse 202 bomblets, effective against armored vehicles and troops, which Tool invoked using cups placed roughly 20 meters apart on the desert floor, so far it was hard to see from one to the next. To get a sense of scale, the U.S. Air Force dropped 10,035 of the CBU-87s during Desert Storm.

And now, to Tool's amazement, the CBU-87 is also a toy, available for purchase over the Internet. The miniature CBU-87 does not explode, but to Tool it is every bit as dangerous. "It's surreal," he says, staring at the package. "See the Operation Enduring Freedom sticker? 'Bombs away! Recommended for ages 10 and up.' I probably don't need to buy it to remember it, but if I don't own it, I'll think I made it up in a couple of years."

For his piece "393," which commemorates the number of U.S. combat deaths the first year of the Iraq war, Tool made and decorated 393 ceramic cups by hand. "Each of the 393 U.S. dead were raised by someone. Someone whipped their ass and made sure they got to school," he explains. "Then they went to Iraq and were killed." After firing and glazing the cups, Tool shot each of them with a pellet gun and videotaped it shattering. Each set of fragments was displayed on an individual base in front of a screen playing the 50-minute video of their destruction. The work has been shown at UC Berkeley's Worth Ryder Gallery and at California State University, Long Beach.

Why did he shoot the cups? "Each of the 393 cups could have remained unbroken for thousands of years," he explains. "Each of the 393 dead could have gone on to affect changes that could have changed the world." He adds that if a similar video were made, with five seconds honoring each Vietnamese killed in what that country calls "the American War," it would take more than three months to watch.

For the "Letter" project, which he began in 1999, Tool has mailed letters and cups to more than 50 government officials and prominent private citizens around the world. For his shows, he'll display a letter or two, a photograph of the cup he sent, and the response (if any). In January 2001, before the Iraq war began, he wrote to each member of the United Nations Security Council plus the Iraqi ambassador to the U.N. He introduced himself as a former Marine and a vet, and wrote, "I would like you each to have a cup I made, and to thank you for your efforts to avoid another war in Iraq. I am not very optimistic that your efforts will avoid a war but I wanted to thank you for trying."

He concluded the letter with, "Once a person has witnessed a war, they are forever changed."

China refused his package, but the representatives from Chile, the United States, and the United Kingdom replied. The U.K. ambassador to the United Nations, Sir Jeremy Greenstock, wrote that Tool's cup would stay on his desk, and the Secretary of the Navy said that he would display the bowl in a prominent place next to his sign-in sheet at the Pentagon. This means a lot to Tool. "When I was in the Marines, you had to go through the chain of command to talk to people," he says. "Now I'm a civilian, so I can write to the president, to the secretary of defense if I want. They don't have to respond, but I can tell them how I feel."

"Tick-tock, tick-tock"

Tool will be graduating in May with his Master of Fine Arts. He isn't sure how he'll support his family - he and his wife just had their first child, a son, in October - since he finds the idea of profiting from his kind of work repugnant. He would like to teach ceramics, but doesn't have high hopes for getting such a position, given how poorly the Introduction to Visual Thinking class he's teaching this semester has gone. Ten out of the 26 students registered for the class dropped it in the first few weeks, he chuckles ruefully. That could have something to do with his existential drill-sergeant style. He says he told them, the only thing he'd guarantee is that at the end of each class, "You will be three hours closer to the moment you will die. It's like, tick-tock, tick-tock, [expletive]…If you come in here and you don't max out your time, I will punish you."

While Tool acknowledges that at some point, he will have to find a new artistic obsession - that "eventually people will ask me why the hell I'm doing this when I will have been out of the Marines for 20 years" - he doesn't see that day coming anytime soon. The Iraq war is simply a continuation of the Gulf War, he says, pointing out that the United States has been bombing the country continuously (in the no-fly zone) since 1991, and there will be more wars that could be avoided.

Cup by cup, letter by letter, Tool is trying to do his part to stop the carnage. He is not optimistic. Asked about a print of Picasso's "Guernica" (1937), the most famous antiwar artistic statement in history, hanging high on the wall of his studio, he says he put it there "to keep [stuff] in perspective. That's before Auschwitz, before Nagasaki, Guadalcanal and all these other horrible things. So if Picasso couldn't stop war with that brilliant piece of work, I don't have a chance."

A small sample of Tool's work will be on view through November 18 at the ASUC Art Studio Gallery, on the lower level of the MLK, Jr. Student Union (enter off of Lower Sproul Plaza). There will be a closing reception held at the gallery on Nov. 18 from 5-7 p.m, at which Tool will give away 100 cups.