UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

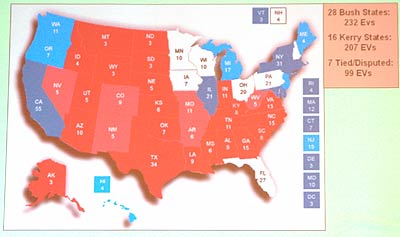

RED SEA: Pollster Mervin Field's slide showing the Electoral College breakdown as of Nov. 1: Field believes Bush has 232 solid electoral votes; Kerry, 207; and 99 are up for grabs. |

At Berkeley, pollsters' election-eve handicapping puts Bush and Kerry in dead heat

Election Day information • Forgot where your polling place is? Smartvoter.org can tell you. • Confused about all the California propositions on today's ballot? Berkeley's IGS has a guide that will help |

BERKELEY – Despite the ocean of polling data available for political junkies everywhere, the presidential contest between President George W. Bush and Senator John F. Kerry is still too close to call with any scientific certainty - even for the pollsters. That was the message delivered in two rapid-fire election-eve presentations by polling and election experts held at UC Berkeley's Institute of Governmental Studies library.

"A presidential election is not one national election, but 51 separate elections," veteran pollster Mervin Field reminded the small audience of mostly Berkeley faculty and graduate students. Field is the founder of Field Research Corp., a nationally recognized expert on political polling, and longtime head of its Field Poll. "Relying on national polls can sometimes create a misleading picture of how the race is going."

Field has been surveying voters for decades, even before he created the California Poll in 1947 (later renamed the Field Poll). (BAP photos) |

Not only is each state's race crucial in determining the electoral vote totals, but surveys by different polling groups cannot be easily compared and contrasted, he said. They are conducted with different questions, worded in different ways, and use varying methods to determine who gets counted as a likely voter. Also, surveys are adjusted in unique ways for demographics, party turnout, and other variables.

With that broad caveat, Field proceeded to show averages of up-to-the-minute national polls that had Bush hovering at 48% to Kerry's 47%. "I've been looking at distributions all my life, but with this, my mind is just floating," Field said. "I have never seen anything like it."

Another speaker, J. Merrill Shanks, a political science professor at UC Berkeley and the co-director of the Public Agendas and Citizen Engagement Survey, said that while PACES methodology was not good for "horse-race type analysis," his data indicated that Bush was inching ahead in non-battleground states and Kerry leading slightly in the swing states. Kerry was also doing significantly better among people who didn't vote in 2000, "which includes a lot of younger people," added Shanks.

The PACES poll was begun in 2001 to track how voters' opinions on the issues correlate with their voting records in an ongoing, in-depth way. The PACES team polls a small sample of adult U.S. voters (100 to 400) continuously, every working day, and will also conduct a follow-up survey after the election. Respondents are asked to indicate their opinions on more than 30 topics, including the Iraq war, civil liberties, abortion, the environment, homosexuality, health care, race, and free trade; whether they identify themselves as Republican, Democrat, or independent; and how they intend to vote.

PACES data can help explain why there have been such wild swings — of several percentage points from week to week and even day to day - in the polls, offered Shanks. "A lot of people see the two candidates as more or less equal in merit, just a shade different," he explained. "And whatever you might think, they are not complete fools. They represent combinations of interests on issues that rise and fall in response to news." (Read about which issues are important to 15 Berkeley students in this Point of View feature.)

For that reason, Field argued, polls should continue to play a useful role even though the public may be sick of them. "Even if Bush doesn't read newspapers, like he says, he should still see how America is thinking," Field said, apologizing if this sounded overly critical of one candidate in particular. "Bush campaigned in 2000 as a uniter, not a divider, but no one in their right mind could see this incredible division in the country and not think something was wrong."

Henry Brady (rear) is the director of Berkeley's Survey Research Center and a national expert on voting machines; J. Merrill Shanks is the co-creator of the Public Agendas and Citizen Engagement Survey. |

Returning to the horse race at hand, Field carefully enumerated all the variables that made it impossible to place any sure bets. Not only is Ralph Nader a factor who could siphon votes from Kerry, as he did from Al Gore in the 2000 election, but the Libertarian Party candidate, Mark Badnarik, is on the ballot in 49 states, Fields reminded the audience, and could very well draw votes from Bush. The race was so close in the swing states - his analysis showed Bush trailing with just 0.4 percent in Ohio and 0.2 percent in Wisconsin, for example - that even such marginal third-party candidates could have a decisive impact.

More frighteningly for fatigued voters who just want this election over, Field said, there was a not-as-farfetched-as-you-hope possibility of a tie. A couple of Ohio State University professors had run computer simulations and come up with 33 possible combinations (out of more than 100,000) that could result in a 269-269 Electoral College tie. "The furor surrounding the 2000 Florida recount would be child's play in comparison," sighed Field, explaining the complicated method by which the (new) House of Representatives would then pick the president and the Senate would choose the vice president. (One bizarre permutation of this possibility has Kerry's running mate John Edwards ending up as both vice president and president … don't ask.)

In response to a question from the audience, Field resurrected election-eve poll data from the 2000 presidential contest that showed Bush several points ahead of Al Gore, who went on to win the popular vote by a 0.5 percent margin of a half-million votes, but lost the contest in the Electoral College. He reminded the group that since that time, there has been a reapportionment of Electoral College votes to bring the states in line with population data from the 2000 U.S. Census. Seven electoral votes have been taken from states that voted for Gore and given to those that voted for Bush.

Near the end, as audience member after audience member probed for something, anything, that would give them a definitive answer on who might be inaugurated in January, the host of the event, UC Berkeley political science and public policy professor Henry Brady, broke down and shared his guess for the election's outcome.

The director of Berkeley's Survey Research Center and the California Census Research Data Center, Brady predicted that - based on the inaccuracy of the 2000 election-eve polls, the general over-sampling of Republicans in most polls, the probability that many likely voters have been ignored, that turnout and new mobilization seems to be running in the Democrats' favor - "Kerry will win the popular vote by a 1.5 point margin and the Electoral College by 30 votes. But I wouldn't put money on it."

No one, it seems, feels sure enough to bet.

Join Berkeley's Institute of Governmental Studies faculty and students as they watch and analyze election returns on the big-screen TV in the IGS library at 109 Moses Hall, starting at 4 p.m. Tuesday, November 2.