UC Berkeley Press Release

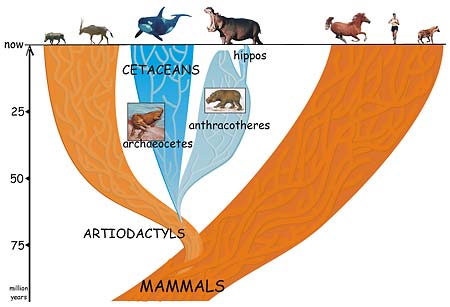

The family tree of modern whales and their first cousin, the hippopotamus, showing how the now-extinct anthracotheres are the link between their distant ancestors. (Credit: Jean-Renaud Boisserie/UC Berkeley) |

UC Berkeley, French scientists find missing link between the whale and its closest relative, the hippo

BERKELEY – A group of four-footed mammals that flourished worldwide for 40 million years and then died out in the ice ages is the missing link between the whale and its not-so-obvious nearest relative, the hippopotamus.

The conclusion by University of California, Berkeley, post-doctoral fellow Jean-Renaud Boisserie and his French colleagues finally puts to rest the long-standing notion that the hippo is actually related to the pig or to its close relative, the South American peccary. In doing so, the finding reconciles the fossil record with the 20-year-old claim that molecular evidence points to the whale as the closest relative of the hippo.

"The problem with hippos is, if you look at the general shape of the animal it could be related to horses, as the ancient Greeks thought, or pigs, as modern scientists thought, while molecular phylogeny shows a close relationship with whales," said Boisserie. "But cetaceans – whales, porpoises and dolphins – don't look anything like hippos. There is a 40-million-year gap between fossils of early cetaceans and early hippos."

In a paper appearing this week in the Online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Boisserie and colleagues Michel Brunet and Fabrice Lihoreau fill in this gap by proposing that whales and hippos had a common water-loving ancestor 50 to 60 million years ago that evolved and split into two groups: the early cetaceans, which eventually spurned land altogether and became totally aquatic; and a large and diverse group of four-legged beasts called anthracotheres. The pig-like anthracotheres, which blossomed over a 40-million-year period into at least 37 distinct genera on all continents except Oceania and South America, died out less than 2 and a half million years ago, leaving only one descendent: the hippopotamus.

Skulls of a 9 million-year-old anthracothere, Merycopotamus medioximus, from Pakistan's Siwalik Hills (above) and a contemporaneous fossil hippopotamus (Hexaprotodon sivalensis) from the same area exhibit many similarities, including the eye socket, which protrudes above the skull to let the animals see above water while most of their head is submerged. (Anthracothere skull courtesy of Harvard University & Geological Survey of Pakistan; hippo skull from the Natural History Museum, London) |

This proposal places whales squarely within the large group of cloven-hoofed mammals (even-toed ungulates) known collectively as the Artiodactyla – the group that includes cows, pigs, sheep, antelopes, camels, giraffes and most of the large land animals. Rather than separating whales from the rest of the mammals, the new study supports a 1997 proposal to place the legless whales and dolphins together with the cloven-hoofed mammals in a group named Cetartiodactyla.

"Our study shows that these groups are not as unrelated as thought by morphologists," Boisserie said, referring to scientists who classify organisms based on their physical characteristics or morphology. "Cetaceans are artiodactyls, but very derived artiodactyls."

The origin of hippos has been debated vociferously for nearly 200 years, ever since the animals were rediscovered by pioneering French paleontologist Georges Cuvier and others. Their conclusion that hippos are closely related to pigs and peccaries was based primarily on their interpretation of the ridges on the molars of these species, Boisserie said.

"In this particular case, you can't really rely on the dentition, however," Boisserie said. "Teeth are the best preserved and most numerous fossils, and analysis of teeth is very important in paleontology, but they are subject to lots of environmental processes and can quickly adapt to the outside world. So, most characteristics are not dependable indications of relationships between major groups of mammals. Teeth are not as reliable as people thought."

As scientists found more fossils of early hippos and anthracotheres, a competing hypothesis roiled the waters: that hippos are descendents of the anthracotheres.

All this was thrown into disarray in 1985 when UC Berkeley's Vincent Sarich, a pioneer of the field of molecular evolution and now a professor emeritus of anthropology, analyzed blood proteins and saw a close relationship between hippos and whales. A subsequent analysis of mitochondrial, nuclear and ribosomal DNA only solidified this relationship.

Though most biologists now agree that whales and hippos are first cousins, they continue to clash over how whales and hippos are related, and where they belong within the even-toed ungulates, the artiodactyls. A major roadblock to linking whales with hippos was the lack of any fossils that appeared intermediate between the two. In fact, it was a bit embarrassing for paleontologists because the claimed link between the two would mean that one of the major radiations of mammals – the one that led to cetaceans, which represent the most successful re-adaptation to life in water – had an origin deeply nested within the artiodactyls, and that morphologists had failed to recognize it.

This new analysis finally brings the fossil evidence into accord with the molecular data, showing that whales and hippos indeed are one another's closest relatives.

"This work provides another important step for the reconciliation between molecular- and morphology-based phylogenies, and indicates new tracks for research on emergence of cetaceans," Boisserie said.

Boisserie became a hippo specialist while digging with Brunet for early human ancestors in the African republic of Chad. Most hominid fossils earlier than about 2 million years ago are found in association with hippo fossils, implying that they lived in the same biotopes and that hippos later became a source of food for our distant ancestors. Hippos first developed in Africa 16 million years ago and exploded in number around 8 million years ago, Boisserie said.

Now a post-doctoral fellow in the Human Evolution Research Center run by integrative biology professor Tim White at UC Berkeley, Boisserie decided to attempt a resolution of the conflict between the molecular data and the fossil record. New whale fossils discovered in Pakistan in 2001, some of which have limb characteristics similar to artiodactyls, drew a more certain link between whales and artiodactyls. Boisserie and his colleagues conducted a phylogenetic analysis of new and previous hippo, whale and anthracothere fossils and were able to argue persuasively that anthracotheres are the missing link between hippos and cetaceans.

While the common ancestor of cetaceans and anthracotheres probably wasn't fully aquatic, it likely lived around water, he said. And while many anthracotheres appear to have been adapted to life in water, all of the youngest fossils of anthracotheres, hippos and cetaceans are aquatic or semi-aquatic.

"Our study is the most complete to date, including lots of different taxa and a lot of new characteristics," Boisserie said. "Our results are very robust and a good alternative to our findings is still to be formulated."

Brunet is associated with the Laboratoire de Géobiologie, Biochronologie et Paléontologie Humaine at the Université de Poitiers and with the Collège de France in Paris. Lihoreau is a post-doctoral fellow in the Département de Paléontologie of the Université de N'Djaména in Chad.

The work was supported in part by the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Tchadienne, which is co-directed by Brunet and Patrick Vignaud of the Université de Poitiers, and in part by funds to Boisserie from the Fondation Fyssen, the French Ministère des Affaires Etrangères and the National Science Foundation's Revealing Hominid Origins Initiative, which is co-directed by Tim White and Clark Howell of UC Berkeley.