UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

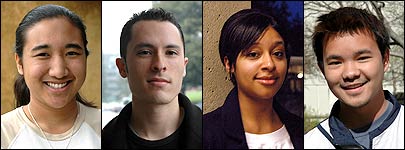

Multiracial Berkeley students Ai-Ling Malone, Josh Fisher, Amina Sutherland- Stölting, and Rey Doctora. (Bonnie Powell photos) |

Mixed emotions: The multiracial student experience at UC Berkeley

BERKELEY – "What are you?"

That's the question Robert Allen, adjunct professor of African American Studies and Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley, writes on the chalkboard when students first file in for his "People of Mixed Racial Descent" class. It's also the question that complete strangers have asked Ai-Ling Malone, a third-year business administration and economics major, all her life; Ai-Ling, whose mom is Chinese and whose dad is African-American, says it has never bothered her. Josh Fisher (Chinese and white), an environmental sciences Ph.D. student, almost never hears it. Third-year industrial engineering major Rey Andrew Perocho Doctora (Filipino and Chinese/Japanese) mostly hears it only from Asian people: "I have Chinese eyes but my skin is dark, so they find it hard to figure me out."

| Mix it up Did this article strike a chord with you? We invite Berkeley students, faculty, staff, and alumni to share their points of view on this topic with the campus community. We are publishing the most thoughtful e-mailed responses on a Point of View: Mixed Forum page. Please limit your response to no more than 200 words. You must include your full name, year and major (or title and department); for verification purposes, you must send from a Berkeley e-mail account. Submissions may be edited for length and clarity. Write to bpowell@berkeley.edu. |

According to Allen, the problem with the question is that "They're asking not who, but what are you, like you're some kind of bizarre creature. It is really an insulting question because it denies your humanity." Even the more tactful variations - "What's your background?" or "Where are you from?" - are quite familiar to multiracial people, he says, and can be just as irritating. However it's framed, the point of the query is the same: The questioner is trying to fit the person into one of four or five mental boxes for race, but something seems off. And while the motivation may differ — some people are genuinely interested, while others just want a shortcut for their racial stereotypes and cultural biases — the multiracial person still ends up being made to feel different, over and over again.

At UC Berkeley, an eye-opening 22.9 percent of all respondents identified themselves as "multi-racial or multi-ethnic" on the 2004 UC Undergraduate Experience Survey. Across the UC system, the average was 25.8 percent. Thanks to the growing numbers of mixed young people, a journey that often begins in college as a personal quest for identity is starting to gather force as a political movement.

'Most of the students who were coming to our [Hapa] meetings are white and Asian, and their experience is very different from mine. But even if there's diversity within the community, there are things we can all relate to.' -Ai-Ling Malone, third-year business administration and economics major |

'You don't count'

Ai-Ling's middle name is Jamila. Her two sisters also have Chinese first names and African-American middle names; for her three brothers, the pattern is reversed. Her parents were similarly committed to making sure the six Malones got equal exposure to both sides of their culture. They went to Chinese school on Friday nights followed by Chinese dance lessons, while their father gave them books on slavery and African-American history to read and "told us all about Rosa Parks and Malcolm X - many times," Ai-Ling says. They visited Taiwan and celebrated Chinese New Year; meanwhile, when Ai-Ling's father learned that their adopted hometown of Davis, California, did not have a Martin Luther King, Jr. celebration, he started one.

Given her father's community involvement - he founded the Multicultural Christian Church of Davis and campaigned with Reverend Jesse Jackson against Proposition 209 - it's not surprising that Ai-Ling and her siblings gravitated to leadership roles in their high school's Black Student Union. "We picked that identity," says Ai-Ling, but it also sounds as if it picked them. In high school, "Asians were more rejecting - they would say, 'You don't count,' as if I wasn't Asian enough."

It wasn't always smooth sailing among black high school students, either. While Ai-Ling felt accepted by her classmates, she remembers going to a Black Student Union conference at a different school and being in an elevator with several other attendees. One of them looked her up and down and said, "What are you doing here?" Although her friends jumped in to set the girl straight, Ai-Ling was stung.

She and her siblings have encountered racism from both sides. "There's a certain stereotype about what it means to be black, which can be negative," she says. A white high-school guidance counselor asked - looking at Ai-Ling's sister and not her transcript - whether she wanted to go to college, and suggested that if so, she take a remedial math class. Her sister had already taken and excelled at calculus. But sometimes it's black people who enforce society's stereotype. "If you're taking AP [college-level] classes or doing well in school, it's like you're not really black. Or you better talk and act a certain way," she says. "My dad was always like, 'No way, do not fall into that trap.'"

Finding Hapa-ness

These days, Ai-Ling is much more confident about who she is. "Growing up in a monoracially dominated society, it was sometimes difficult to assert a biracial identity as I have now," she writes in an e-mail. "Having two backgrounds does not exclude me from being either. I am proud of my dual heritage."

Berkeley freshmen combinations

*International students are not included |

This year the Berkeley Hapa students decided to broaden the group's mission, formally welcoming mixed students from any ethnic group, not just those who are part Asian. The club is now called the Multi-racial, Multi-ethnic, and Multi-cultural Student Union - "Mixed," for short. "Most of the students who were coming to our meetings are white and Asian, and their experience is very different from mine," says Ai-Ling, who is trying to recruit more non-Hapa students into Mixed. "But even if there's diversity within the community, there are things we can all relate to."

This semester, she is co-teaching a UC Berkeley DeCal course called Ethnic Studies 198: Multiracial Issues. About half the 20 people taking her class are multiracial, with the remainder in interracial relationships; Allen's 150- to 250-person class tends to be similarly divided. Both are discussion-based and look at historical constructions of race; Ai-Ling's also addresses biological and mental health issues, interracial dating and marriage, and the role of multiracial celebrities.

'Loving' boom

The multiracial movement is a young one in both senses of the word. The 2000 U.S. Census was the first to allow respondents to choose more than one box to describe their race. More than 6.8 million people, or 2.4 percent of the population, did so - and 42 percent of them were under 18. Several caveats apply here: respondents were asked to choose from White, Black, American Indian, Pacific Islander, Asian, and Other, with a secondary question asking if they were Hispanic in origin, so many "full" Latinos may have counted themselves as mixed race. Also, the real number of young multiracial people is probably even higher, as research shows that many interracial couples do not report their children as multiracial. Those who are part white account for nearly three-quarters of the Census's mixed-race respondents; double minorities like Ai-Ling are the smallest group of mixtures. (See the breakdown of mixtures in the United States and California.)

'In America, your life chances are still determined by race. In the end, you become a member of a race because of your heritage, not your appearance.' -Robert Allen, UC Berkeley adjunct professor

of African American Studies and Ethnic Studies (Ruth

Morgan photo) |

Much of the academic research on the mixed-race community began at Berkeley. The "People of Mixed Racial Descent" class was the first of its kind in the nation. It was started in 1980 by Terry Wilson, a Berkeley professor of Native American Studies and the son of a Potawatomi Indian father and a white mother. Several of the course's early teachers, like Ph.D. student Cynthia Nakashima, have gone on to write landmark texts about the multiracial experience.

The class is even more heavily subscribed now. "For many of the students it's the first chance they've had to talk about their experience in a supportive environment," says Allen. When he teaches the class - alternating with African-American Studies chair Stephen Small - he emphasizes the artificiality of the idea of race, reminding students that it has no scientific basis. In 1998 the Anthropological Association of America actually released a formal statement to that effect: "Evidence from the analysis of genetics (e.g., DNA) indicates that most physical variation, about 94 percent, lies within so-called racial groups. This means that there is greater variation within 'racial' groups than between them."

'I always felt white, because I looked more white than Asian.…It always amazes me when someone asks if I'm part Asian, because I just don't see it.' -Josh Fisher, environmental sciences '01 and current Ph.D. student |

"Mystery meat"

Josh Fisher, who went to a diverse high school in Los Angeles with a large Persian population, says he was "the only white guy on my high school basketball team," then laughs. "Did you hear what I just said? Well, the black guys always called me 'white boy.'" Josh's parents divorced when he was in elementary school, but his Chinese mother raised him according to his white father's Jewish faith, complete with Hebrew school and a bar mitzvah.

Josh and his best friend since pre-school, who is also half Chinese and half white, attended several meetings of Berkeley's Hapa Issues Forum as undergraduates, but they went for the social rather than the educational activities. "You're not going to find too many issues with me," Josh says. "I always felt white, because I looked more white than Asian. I've heard Persian and Latino; most people think I'm Italian. It always amazes me when someone asks if I'm part Asian, because I just don't see it." The only conflict Josh admits to feeling about his two sides is when he has to decide whether to eat the "mystery meat" in Chinese restaurant dumplings in case it's pork, forbidden by Judaism.

'People have mostly accepted me for who I am. Since I have three different bloodlines, I feel like I can jump around with lots of different groups.' -Rey Andrew Perocho Doctora, third-year

IEOR major |

Rey Doctora, whose Filipina mother and Chinese/Japanese dad both grew up in the Philippines, has also never felt marginalized for being mixed. He attended Long Beach Polytechnic in Southern California, which was mostly Asian and white.

"I didn't fit in with any one group there, I sort of blended with all of them," he says. Here at Berkeley's College of Engineering, "people have mostly accepted me for who I am. Since I have three different bloodlines, I feel like I can jump around with lots of different groups. But maybe I look for people who don't stereotype other people."

"Over it"

Amina Sutherland-Stölting has yet to find a group in which she feels fully comfortable, but she has come to accept always feeling like an outsider. "At one point in my life, being multiracial was all-consuming," she says. "Now I'm sort of over it." And yet, she agreed to be interviewed because her older sister told her that "I needed to stand up for the community, even if there isn't really one, just to lay some building blocks for the future."

Amina's Dutch mother met her black Costa Rican father at a wedding. The couple lived in Holland, where Amina's sister was born, before moving to Los Angeles. Both her parents were extremely aware of exposing her to both sides of her heritage, taking the family for summer trips back to Holland and living for a year in Costa Rica when Amina was 11. "I loved it there. It was the first time I'd lived anywhere that I looked like the people," she recalls.

'I grew up completely differently than some of the black people I have met here. I had ballet lessons and went horseback riding and spent summers in Holland. Does that mean I can't be black?' -Amina Sutherland-Stölting, fourth-year

integrative biology major |

It wasn't all smooth sailing. Amina remembers the first time she realized other people were making those exceptions for her. She and a black classmate went to volleyball camp at a mostly white private school. Weeks later, the teacher was talking to the class about their racial experiences, and the other girl confessed she had hated that volleyball camp, that she felt like they didn't want her there, that they were all racists. Amina, who was sitting behind her, jumped in: "Wait, I didn't feel that at all." The girl's response floored her. She said to Amina, "You don't count - you're not black!"

"Everyone in the class laughed," recalls Amina, angrily wiping away tears at the still-painful memory. "It was the first time it had ever dawned on me that black people didn't consider me black, like I didn't belong with them. All along I had thought they thought, "Well she's mixed, but she's black.' I was really, really upset."

She had hoped to find more of a community at Berkeley, but says that the original Hapa Issues Forum mission hadn't seemed to include her, and that the "People of Mixed Racial Descent" class, which she took last year as a junior, was a disappointment. Instead of the common experience she was hoping for, the class felt divided between those who were half white and other mixes. "They were like, 'Well, you obviously can't pass, but I've never been discriminated against.' I don't know what I was looking for - maybe the rainbow coalition? - but I didn't find it in that class."

Shortly after the class ended, Amina penned a powerful column for the Daily Cal about her feelings of isolation. "Blasted expectations!" she wrote. "I still like to believe people with mixed-race backgrounds share something in common..So as the class sputtered to an end, so does this column-nothing is cleared up." Her words touched a nerve in readers. "I got 25 or so e-mails - from freshmen, from faculty, from people in their 70s," she says, still amazed. "Mixed people were coming out of the woodwork to say thank you, because someone finally put it out there."

Amina still considers herself black, but with reservations. "I feel like the history of African-Americans in this country is not my history. That's not to say there weren't slaves in Costa Rica, just that Black History Month is not really about me," she says. "I grew up completely differently than some of the black people I have met here. I had ballet lessons and went horseback riding and spent summers in Holland. Does that mean I can't be black? I don't know. I haven't figured that out yet."

Black like me

Who decides what it means to be "black" for people like Ai-Ling and Amina? Apparently everyone has an opinion. And most tellingly, Amina says it would never occur to her to identify herself as white, nor would her sister, who is much lighter-skinned. According to Allen, the shameful history of slavery in this country, with its legacy of laws like the "one-drop" rule, continues to foil any attempts to imagine a truly color-blind society.

"Although I think we're moving away from that strict two-category system, white or non-white, we still privilege white skin," he says. "If you go to a high-rise office building and start at the bottom, where the mail room and the custodial services are, that's where you'll find most of the darker-skinned people, getting whiter as you reach the executive offices."

The growing numbers of mixed-race people - and the prominence of multiracial celebrities like Halle Berry, Tiger Woods, and Keanu Reeves - may foil attempts to categorize and thus stereotype individuals based on race, but the old racial boxes are more likely to be replaced by a "pigmentocracy," such as a sociologists have identified in Brazil, Allen says. There, "lighter-skinned people start out with more preference, but it's fluid: your money, status, and culture can overcome the color of your skin."

Until the multiracial movement matures and finds its common voice, mixed students like Amina, Josh, Rey, and Ai-Ling will continue to befriend other mixed people, struggling to define themselves in a society fixated on skin-based labels. "We float under the radar most of the time, but I think we are looking to group ourselves," says Amina, whose best friend at Berkeley is Persian and white. "It's like if you're both mixed, you can be more relaxed, less likely to judge each other."

And some day, she hopes, the rest of the world will be more interested in knowing the answer to the question "Who are you?" than "What are you?"

More resources — on campus and off

- "The struggle for Berkeley's 'soul as an institution'": The Berkeleyan reports on the March 3, 2005, campus diversity forum in which Chancellor Birgeneau acknowledged the centrality of diversity and inclusion to the campus's mission and Boalt Hall Dean Edley laid out a plan for research into diversity-related issues

- "Giving her best — and then some": Profile of new African American Student Development coordinator Nzingha Dugas

- UC Berkeley Undergraduate Education's Multicultural Student Development Unit

- The MAVIN Foundation, an organization founded by multiracial young people to advocate for mixed-race people and families.

- Generation MIX National Awareness Tour: Five multiracial young people are traveling to college campuses across the U.S. in an RV to jumpstart a dialogue

- MixedmediaWatch.com: An online journal that scrutinizes media treatment of multiracial individuals.