UC Berkeley Press Release

Eminent cell biologist and avid rock climber Morgan Harris has died at 88

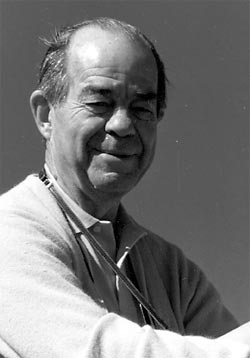

BERKELEY – Eminent biologist and rugged outdoorsman Morgan Harris, professor emeritus of zoology and former chairman of the zoology department at the University of California, Berkeley, died Feb. 14 of pneumonia at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center. Harris, a resident of Kensington, Calif., was 88.

Morgan Harris |

Harris was a noted experimentalist in cell biology and cancer research, though much of his work went against the late 20th century notion that the secret to life lies in our genes. While other researchers were churning out "genes of the month," according to colleague Richard C. Strohman, UC Berkeley professor emeritus of molecular and cell biology, Harris was pursuing experiments that showed that genes were not as important as what controls the genes, what turns them on and off.

"Morgan often said that life is a lot more complicated and complex than simply looking at genes, that you can't reduce life to an analysis of the genes," Strohman said.

"He was a philosopher, a designer of questions, a theorist rather than a bean counter. He was ahead of the game, and I think he knew that."

Today, cell and molecular biology is undergoing a revolution as scientists concentrate more on the regulatory apparatus in the cell. Areas such as proteomics and bioinformatics focus on the complexity of interactions within the cell and among genes, not just the genes themselves.

Much of Harris's work in cell culture explored the influence of the environment on the behavior of cells, and he was one of the first to recognize the phenomenon of epigenetic inheritance of traits, that is, inheritance of traits not encoded as a mutation in the genes. He noted this specifically about the biological mechanisms of drug resistance. His last paper in 1995 reported experiments showing that the history of cells in culture affects their response to drugs.

"Morgan showed that you can produce long-term changes in the behavior of cells not only by causing mutations, which are changes in the sequence of nucleotides in DNA, but by changing molecules that are bound to DNA and which modify genes," said Harry Rubin, professor emeritus of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley. "These changes affect whether or not a gene is active, but they are not genetic, they are epigenetic."

His findings have been verified in many fields of science, including neurobiology, the area of research being pursued by Harris's sons. His elder son, Roger Harris, is a professor of biological structure and teaches neuroanataomy at the University of Washington, while Ronald Harris-Warrick is a professor and chair of the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University.

"Morgan was a man of the highest integrity and soundness of judgment, and always ready to help when asked," Rubin said. "I have the greatest admiration and respect for him."

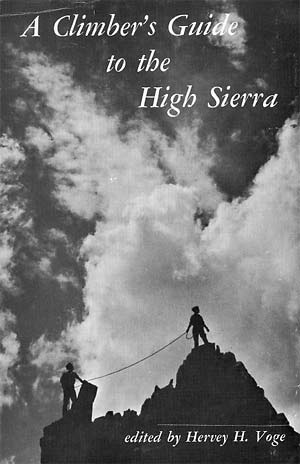

Famed photographer Ansel Adams captured Morgan Harris (on peak) and David Brower climbing in the Minarets. This photo graced the cover of the 1954 edition of A Climber's Guide to the High Sierra. |

Morgan Harris greatly loved the outdoors, and in his early years was a pioneer of roped rock climbing in Yosemite Valley. In 1936, he was part of a team that climbed Royal Arches, employing for the first time the pendulum traverse, that is, the use of a rope to swing from point to point. Often climbing with the late Sierra Club leader David Brower, they made the first ascent of Cathedral Chimney in 1936 and together established 11 routes in Yosemite Valley. In all, Harris achieved 14 first ascents in Yosemite Valley, including the "Rotten Log" route on Royal Arches. He also established the "Shaky Leg Crack" route on the east face of Mt. Whitney, California's highest peak.

He also climbed with nature photographer Ansel Adams, who snapped a picture of Harris and Brower scaling the side of a mountain that later graced the cover of one of the early climbing guides.

In 1981, he was selected to serve on a national committee to prepare a master plan for the future of Yosemite National Park that resulted in many improvements in his beloved valley. Although he eventually gave up rock climbing, he continued to ski, hike and backpack, and became a passionate birdwatcher. He accumulated a world list of almost 2,500 species.

An inveterate traveler, Harris made trips to the wild corners of every continent and spent many happy years of sabbatical leave all over the world.

Harris was born in St. Anthony, Idaho, on May 25, 1916, but grew up in Oakland. During his high school days, he nurtured his love of nature by forming a bird-watching club with his classmates. Members of that group continue to meet annually.

As a teenager, he joined the Sierra Club, where he learned about rock climbing with ropes - a technique mostly used in Europe at the time. He was among the first to try it in California in the 1930s.

Harris received his B.A. and Ph.D. at UC Berkeley. In 1945, he became a professor of zoology on the campus, a position he held until his retirement in 1981, and served as chair of the department from 1957 to 1968. He developed a campus laboratory for tissue culture and was president of the national Tissue Culture Association. His 1964 book, "Cell Culture and Somatic Variation," is an unparalleled classic of the field, Rubin said.

After his retirement, he continued to publish science articles into the late 1990s and to work in his campus laboratory.

"He had a very long and happy relationship with Cal," said Harris-Warrick, his son.

Harris is survived by his wife, Lola, of Kensington, and sons, Roger of Seattle and Ronald of Ithaca, N.Y. His first wife, Marjorie, died in 1985. He is also survived by four grandchildren.

The family requests that, in lieu of flowers, donations be sent to the Golden Gate Chapter of the Audubon Society, 2530 San Pablo Ave., Suite G, Berkeley, CA 94702-2047. A celebration of his life will be announced at a future date.