UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

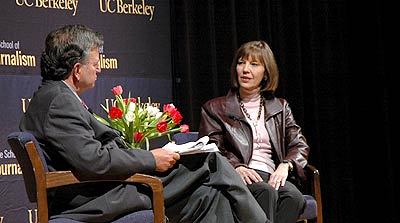

Investigative journalists Lowell Bergman, an adjunct professor in Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism, and Judith Miller, New York Times reporter, discuss the war on confidential sources. (Bonnie Azab Powell photos) |

Controversial reporter Judith Miller plans to defend journalism's role in a democracy - all the way to prison

Webcast: "The

Consequences of Confidential Sources: Jail?" | 1 hour Webcast: "The

Consequences of Confidential Sources: Jail?" | 1 hour |

BERKELEY – "[Journalists] are not perfect. We're not saints," New York Times reporter Judith Miller said acidly to a UC Berkeley audience last night (March 17). "But try running a functioning democracy without a free press."

If the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist seemed defensive, it is because she is under heavy fire on two fronts. In a few weeks, she may go to prison for as long as 18 months for refusing to reveal confidential sources. She has been subpoenaed as part of a federal investigation into the White House leak of CIA operative Valerie Plame's name to columnist Robert Novak.

Meanwhile, ever since the fall of Baghdad in 2003, Miller has faced bitter accusations from both her peers and the public: they charge that in the run-up to the Iraq war, she was tricked by - or worse, colluded with -other confidential sources and the Bush administration into writing articles that strongly indicated Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. No WMDs have been found, and critics have been baying for Miller's blood for the past two years.

Miller's position, as she repeated several times during the Berkeley event and during an interview earlier that day for KQED "Forum," is "You go with what you've got." She was referring both to her WMD sources and the questionable whistle-blowers she is protecting, but it's a statement her critics ought to keep in mind. Miller may be an imperfect martyr for the First Amendment cause, but with 15 other journalists battling a secrecy-loving government over their own confidential sources, you go with what you've got.

Weapons of mass deception

True to the event's billing as "The Consequences of Confidential Sources: Jail?," both Miller and Lowell Bergman, her interviewer from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, preferred to focus on her stand for the First Amendment. Bergman touched on the subject of Miller's prewar reporting with obvious reluctance. He read only two of the stack of questions submitted on cards by the small audience, dismissing them as all being in the same harsh vein about WMDs and [Iraqi exile] Ahmed Chalabi, "our mutual acquaintance." Bergman's own questions for Miller were so gentle that they were more cotton balls than softballs, somewhat surprising given his tough-reporting credentials - he founded the Center for Investigative Journalism, and was a longtime producer for CBS's "60 Minutes," and is best known outside media circles for Al Pacino's heroic portrayal of him in the film "The Insider," about Bergman's investigation into the tobacco industry.

Earlier that day in a joint radio interview with Miller, Bergman had shown where he stood on the issue of her WMD reporting. When "Forum" host Michael Krasny began reading out bare-knuckled e-mails from listeners, Bergman jumped to Miller's defense before she had a chance to speak.

'I could be going to jail for a story I didn't write, for reasons I don't know, for something that may not actually even be a crime.' -Judith Miller |

In May of last year the New York Times published what many considered a belated mea culpa for its Iraq coverage. Although the paper did not name Miller, it included references to several of her stories that relied on Chalabi or other Iraqi exiles and unnamed intelligence sources. (Slate journalist Jack Shafer undertook an excoriating look at Miller's articles in 2003 and has since dogged her in several additional pieces.)

Miller argues that if she was duped by her unnamed sources, so was the Bush administration - and she's not apologizing for believing there were WMDs in Iraq until the president does. "I think I was given information by people who believed the information they were giving the president," she told Bergman. "When the president asked, you know, 'What about this WMD case? Are we sure about this?' [then-CIA director] George Tenet said to him, 'Mr. President, this is a slam dunk.' The people I talked to certainly thought that." Other WMD believers, she said, included the entire U.S. intelligence community as well as French, English, and Israeli agencies. The debate, she claimed, was not over whether Saddam had WMDs, but whether it was worth going to war over them.

Even U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix wrote in his recent book he had believed in the WMDs, she concluded triumphantly. (Speaking in Berkeley this time last year, Blix actually said that while he had thought they might exist, he had never found any evidence to confirm his suspicion and would have preferred to continue looking.)

Ultimately, Miller said, she "wrote the best assessment that I could based on the information that I had." She attempted to tie the controversy over her WMD reporting to her current struggle by saying that she had heard after the fact - after she returned from being embedded with an infantry division in Iraq - that there had been people who had reservations about the WMD intelligence she was receiving.

"I wish they had come forward at the time to express those reservations," she said. "To me, this case that I am now involved in emphasizes the importance of getting as many people as possible to come forward with a dissenting view, or allegations of wrongdoing."

A trip to Kafka's Castle

Even for those who have been following the news, the reason why Miller faces hard time may seem bizarre. The background of the case is complicated, but not any more so than a "Sopranos" episode. (Skip ahead to "Not waiving but drowning" if you're fully caught up on the case.)

In February 2002, the CIA sent retired diplomat Joseph Wilson to Africa to investigate a report of murky origin suggesting Iraq had tried to buy uranium yellowcake (material for a nuclear weapon) from Niger. President Bush included the Niger report in his 2003 State of the Union address as hard evidence seen as justifying a pre-emptive strike against Saddam Hussein. In July 2003, Wilson wrote an opinion piece for the Times, "What I Didn't Find in Africa," saying his conclusions that the report was faked had been ignored, and "some of the intelligence related to Iraq's nuclear program was twisted to exaggerate the Iraqi threat." Just who falsified the Niger documents is not known (or has never been made public).

Several days later, syndicated columnist Robert Novak wrote "Mission to Niger," which named Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, as a Central Intelligence Agency "operative on weapons of mass destruction" and said that "two senior administration officials told me Wilson's wife suggested sending him to Niger to investigate" the report - not Vice President Dick Cheney, as Wilson had written. At the time, nobody paid much attention: Novak seemed to be simply trying to substantiate Bush's claim he had never been told of the doubts about Niger yellowcake. After a slow, three-month fuse lit by bloggers, his July column ignited a firestorm. A 1982 law makes it illegal to disclose the identity of a covert agent. The press - including a New York Times editorial - began demanding an investigation into who in the White House leaked Plame's name to Novak.

Novak wrote an interesting follow-up in October 2003 about the brouhaha, in which he stated, "First, I did not receive a planned leak. Second, the CIA never warned me that the disclosure of Wilson's wife working at the agency would endanger her or anybody else. Third, it was not much of a secret." This last point is key, as the 1982 law has a strict definition of who is considered a covert operative, and Plame's identity was public enough for her name to appear in Wilson's "Who's Who in America" entry, as Novak pointed out.

What does Judith Miller have to do with all this? She'd like to know, too. Unfortunately, eight pages of the briefs filed by the federal prosecutor have been redacted for security reasons. They are entirely blank. While she did make some calls about the leak, she did not file a story on it, and says she does not know who called Novak.

So, if the full U.S. Court of Appeals does not grant her appeal in the next few weeks, "I could be going to jail for a story I didn't write, for reasons I don't know, for something that may not actually even be a crime," she said, attempting laughter. "So it's become kind of Kafkaesque."

Not waiving but drowning

It is not only Kafkaesque, agreed Bergman, but it's chillingly reminiscent of the Nixon Administration's tactics 35 years ago to intimidate and bully journalists into revealing their sources in the Black Panther Party. Miller is not the only target in the Plame investigation: Several other journalists were scooped up in the special prosecutor's dragnet, and availed themselves of a loophole the government offered in the form of a "confidentiality waiver." In their zeal to figure out who leaked to Novak, Bush officials required all White House staff to sign agreements saying that any confidential conversations they had had with a journalist were now public, meaning the reporters could tell the prosecutor about them. Miller and Time magazine reporter Matthew Cooper are the only two who decided that the waiver forms were not voluntarily signed and thus could not void their promise of confidentiality.

"These waivers are really pernicious," said Miller. "They're yet another way in which the government is trying to make sure that the only people we talk to are the authorized spokesmen cleared to speak to journalists. And if that the kind of news that people want, that's what they're going to get."

Bergman posed a question that some in the media (and many bloggers) are asking: are the sources she may go to jail in order to protect actually whistle-blowers? Or is she protecting people who were trying to manipulate the media into a backlash against Joe Wilson?

"We don't know what their motivation was. People leak for all kinds of reasons," replied Miller. You can't afford to pick and choose your battles when you're fighting for a principle, she implied. "You can wait for the 'perfect' whistle-blower case . [or] go with what you've got."

In comparison with reporting from wartime Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Iraq, going to jail doesn't much scare Miller, she said. It's a small price to pay for the latitude enjoyed by the press in the United States. In her opinion, "the real heroes of our profession are the people who risk death to get the news out," in countries where they can be jailed simply for criticizing the government. "I don't want to take [the U.S. freedom of the press] for granted. You have to fight for it, and at certain times you have to be ready to defend it," Miller said.

Bye-bye, Deep Throat

Miller may be the most high-profile reporter facing jail, but she is not alone. Fifteen other journalists around the country are battling expensive, draining lawsuits right now. Five reporters, including one from the Associated Press, are currently in contempt of court for refusing to name their sources in a lawsuit by former nuclear physicist Wen Ho Lee, while TV reporter Jim Taricani is under house arrest because he won't tell who gave him a videotape showing a former Providence, Rhode Island, city hall official taking a bribe from an undercover FBI informant.

A majority of states — Miller says 49, other accounts put the number at 31 - have "shield laws" in place to protect journalists from having to testify about confidential discussions, just as they do for doctors, lawyers, spouses, psychiatrists and social workers. New York, Miller's home state, has such a law, and so does Washington, D.C., where she does her reporting. The federal government does not.

The premise of such laws is that without confidentiality, people would be afraid to reveal to the public through the media abuses committed by lawmakers, the government, and anyone in power. The Watergate case depended on a confidential source, Deep Throat, whose identity has never been revealed. More recently, the Abu Ghraib prison scandal would not have been brought to light without anonymous tips from soldiers and intelligence officers.

In February, a bill that would extend the states' shield laws to the federal government was introduced in Congress. As of mid-March, a dozen House members had signed on to H.R. 581, which would prohibit any federal entities from forcing reporters to disclose a confidential source's identity; a similar measure, S.340, had four cosponsors in the Senate. Although the legislation has supporters on both sides of the political aisle, it will be months before it is debated - too late for Miller.

Nonetheless, she urged audience members to write their representatives and senators in support of the bill. This fight is not about Judy Miller, she said, it's about "shutting down the flow of information. I'm not afraid of going to jail for my beliefs. It's a proud American tradition. I am not a martyr, and I don't want to go to jail, but I will."