UC Berkeley Press Release

Researchers create first nanofluidic transistor, the basis of future chemical processors

BERKELEY – University of California, Berkeley, researchers have invented a variation on the standard electronic transistor, creating the first "nanofluidic" transistor that allows them to control the movement of ions through sub-microscopic, water-filled channels.

The researchers - a chemist and a mechanical engineer - predict that, just as the electronic transistor became the main component of microprocessors and integrated circuits, so will nanofluidic transistors anchor molecular processors, allowing microscopic chemical plants on a chip that operate without moving parts. No valves to get stuck, no pumps to blow, no mixers to get clogged.

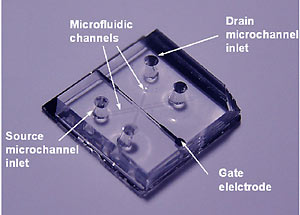

A nanofluidic transistor, too small to see with the naked eye, could allow the creation of microscopic chemical plants that operate without moving parts. As seen in the diagram below, the flow of ions through the liquid inside the nanotube (blue) is shut off by a voltage at the gate (yellow). (Images courtesy Majumdar & Yang labs)  |

"A transistor is like a valve, but you use electricity to open or close it," explained Arun Majumdar, professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley. "Here, we use a voltage to open or close an ion channel. Now that we've shown you can make this building block, we can hook it up to an electronic chip to control the fluidics."

One application Majumdar and colleague Peidong Yang, UC Berkeley professor of chemistry, are exploring is cancer diagnosis. A nanoscale chemical analysis chip could, theoretically, take the contents of as few as 10 cancer cells and pull out protein markers that can tip doctors to the best means of attacking the cancer.

"This is an ideal way to open up cells and identify the proteins or enzymes inside," he said. "An enzyme profile would tell doctors a lot about the kind of cancer, especially in its early stages when there are only a few cells around."

Yang, who built a variation of the transistor using nanotubes, is equally intrigued by the computational possibilities of the device.

"It may sound a little bit far fetched, but we're thinking about whether we can do the same thing with nanofluidic transistors as we can currently with MOSFETs," he said, referring to the Metal-Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect Transistors used in most of today's microprocessor chips. "Using molecules to process information gives you a fundamentally different information processing device."

Majumdar, Yang and colleagues Rohit Karnik, a mechanical engineering graduate student; Rong Fan, a chemistry graduate student; and mechanical engineering students Min Yue and Deyu Li reported their success - the product of three years of effort - in the May issue of the journal Nanoletters. Yang and Majumdar are also faculty scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

One big advantage of nanofluidic transistors, Majumdar said, is that they could be made using the same manufacturing technology that today produces integrated circuits. Nanofluidic channels could be integrated with electronics on a single silicon chip, with the electronics controlling the operation of the nanofluidics. The only microscale parts of the device are the microchannels for injecting liquid.

Majumdar and Yang's team constructed a 35-nanometer-high channel between two silicon dioxide plates, then filled the channel with water and potassium chloride salt. They showed that by applying a voltage across the channel by means of electrodes attached to the plates, they could shut off the flow of potassium ions through the water. This is analogous to the control of electron flow through a transistor by means of a gate voltage.

Such ion manipulations are not possible through microscopic channels because ions in the liquid quickly move to the plates and cancel out the voltage, basically shielding the interior of the liquid from the electric field. Channels less than 100 nanometers across, however, are so small that this shielding doesn't occur, so ions in the bulk liquid can be pushed or pulled by electric voltages.

If the ions are proteins, they can be shuttled through channels lined with fluorescent antibodies for detecting or sensing. If the ions are pieces of DNA, they can be sorted and sequenced. In fact, the authors say, any highly sensitive biomolecular sensing down to the level of a single molecule could be performed with nanofluidic transistors. They demonstrated that labeled, charged DNA fragments could be manipulated in their transistor.

Yang, who is adept at making nanoscale lasers, tubes, wires and other devices, created a version of the transistor using nanotubes with internal diameters of 20 nanometers, proving that the same sort of molecular processing can be done with these innovative structures. While Majumdar foresees putting electronic and nanofluidic transistors on the same chip to provide computer control of chemical processing, Yang foresees the computing and chemical processing being done by the same nanofluidic channels.

"With nanotubes, you have access to much smaller dimensions compared to conventional nanofabrication, but in terms of integration, it's more difficult," Yang said. "For the future, both processes are fundamentally interesting, and eventually devices will combine both."

Majumdar and Yang acknowledge that a lot more work needs to be done, including understanding the surface effects inside nanochannels. In addition, the voltage required to shut off ion flow is now 75 volts, far too high for any of today's integrated circuits. But their team has a few other papers waiting to appear in Nanoletters and in the Physical Review Letters that push the technology farther than this initial paper. They hope to beat the time lag between invention of the transistor in 1947 and creation of the first integrated circuit in 1960.

"We want to be the first to build integrated circuits with just three transistors able to do sorting and eluting, just as a two- or three-bit processor can do multiplexing and addressing," Majumdar said.

The work was supported by the National Cancer Institute's Innovative Molecular Analysis Technologies program and by the Department of Energy. Current work is being funded by the National Science Foundation.