UC Berkeley Press Release

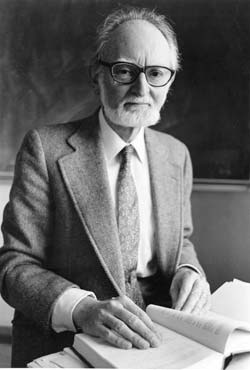

Owen Chamberlain, Physics Nobelist, UC Berkeley professor, LBNL researcher and co-discoverer of the anti-proton, has died at 85

|

Chamberlain died quietly in bed from complications of Parkinson's disease, which had plagued him for many years.

He and fellow UC Berkeley physicist Emilio Segrè, both researchers at the former Radiation Laboratory that is now Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1959 for their discovery of the antiproton, the antimatter equivalent and negatively-charged mirror image of the proton.

"The discovery opened up a whole new field of physics and expanded our understanding of particle physics," said Chamberlain's colleague and former student Herbert Steiner, a professor of physics at UC Berkeley.

"Owen Chamberlain was an example of Berkeley's best – a brilliant researcher with a piercing intellect and a gifted and caring teacher," said UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau. "He's the last of the Nobel generation at Cal that emerged from the Manhattan Project and, with E. O. Lawrence's cyclotron, changed the face of physics."

Chamberlain was a student of Segrè's in the 1940s at UC Berkeley, and after obtaining his Ph.D. under Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago, returned to UC Berkeley as an instructor in the physics department and a researcher in Segrè's group at the Radiation Laboratory. They, together with Clyde Wiegand and Tom Ypsilantis, initially undertook a series of proton-proton scattering experiments. Upon the completion of the Bevatron, then the world’s highest energy particle accelerator, they mounted an experiment that resulted in the first observation of antiprotons in 1955.

Though Carl Anderson of Caltech had discovered in 1932 the first antimatter particle, the positron or antielectron, many prominent physicists doubted the existence of a mirror-image proton. Antimatter is characterized by its explosive annihilation when encountering normal matter, which makes antiprotons an elusive target.

The discovery indicated that all particles have twins of opposite polarity, and many antiparticles have been discovered since then. It remains a mystery, however, why the universe is made mostly of matter with little observable antimatter.

According to Steiner, after receiving the Nobel Prize Chamberlain steered his research program in a completely new direction

|

"He pioneered the use of polarized targets in high energy scattering experiments, which have helped us to understand the forces acting between particles and allowed us to test the symmetry principles underlying the physics," he said. Symmetry principles state, for example, that some interactions look the same when reflected in a mirror or run backwards in time."

One of Chamberlain's gifts was teaching, which he did best one-on-one and with an informality that included his insistence that students call him "Owen." His unique explanations for physical phenomena came to be called "Chamberlainisms" among the students.

At a celebration ten years ago in honor of Chamberlain's 75th birthday, Steiner said that Chamberlain had “developed an uncanny ability to put this basic knowledge together in his own unique way to address whatever question or problem may have been posed. While most of us would sit around pondering and chewing on our hamburger, Owen would make some seemingly irrelevant comments, which upon closer scrutiny were the answer. I suspect Owen must often have wondered what was wrong with the rest of us when we didn’t immediately come up with his obvious solution by ourselves.”

Steiner noted that Chamberlain's office was so filled with stacks of papers "almost to the ceiling" that he could barely squeeze into his chair and had no room for students. As a result, the department mounted a blackboard, henceforth known as "Owen's Blackboard," in the third-floor hallway outside his office so he could interact with his students.

"His office seemed cluttered and disorderly, but if he needed to find something, he knew exactly where it was," Steiner said.

Chamberlain also was "a humanist and social activist," Steiner said, participating in Free Speech Movement demonstrations in the 1960s and speaking out on race relations, the Vietnam War and many liberal causes. In the 1950s and 1960s, he was active in attempts to influence the U.S. administration to achieve a nuclear test ban treaty. And when UC President Clark Kerr was fired by the Board of Regents in 1967 for not coming down hard on protesting students, Chamberlain wrote an impassioned letter to the Regents warning of the dangers of such action. He also was a director for four years of the Ploughshare Fund, a public foundation devoted to nuclear peace.

At UC Berkeley, he was a founding member of the Special Opportunities Scholarship program (SOS) to encourage the enrollment of more minority students on campus.

Although he retired in 1989, Chamberlain continued to attend weekly departmental colloquia, including one just last week, Steiner said.

Chamberlain, a San Francisco native, was born July 10, 1920, the son of W. Edward Chamberlain, a prominent radiologist, and Genevieve Lucinda Owen. He attended public schools in Philadelphia after his family's move there in 1930 and subsequently attended Dartmouth College, from which he graduated in 1941. He then enrolled at UC Berkeley, where he soon joined the Manhattan Project at UC Berkeley and then at Los Alamos. He was present at the first atomic bomb test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945, losing a $5 bet that it would not explode.

In 1946, he joined Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago, where he conducted research on slow-neutron diffraction in liquids while working toward his Ph.D. in physics, which he obtained in 1948 from the University of Chicago.

Returning in 1948 to UC Berkeley, Chamberlain began as a physics instructor, then became an assistant professor in 1950 and a full professor of physics in 1958. His proton- and neutron-scattering experiments were conducted with the 184-inch cyclotron at the Radiation Laboratory on the hill above the campus, while his and Segrè's experiments with the antiproton were conducted with the UC Berkeley Bevatron, at the time the largest "atom smasher" in the world. Using it, Chamberlain achieved the first triple-scattering experiment with polarized protons.

He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a member of the American Physical Society and a former Guggenheim Fellow. Upon his retirement from UC Berkeley, he received the campus's highest honor, the Berkeley Citation.

Chamberlain is survived by his wife, Senta Pugh-Chamberlain (née Gaiser) of Berkeley, and four children by his first wife, Beatrice Babette Copper, who died in 1988 – daughters Karen Chamberlain of Tampa, Fla.; Lynne Guenther of Ithaca, N.Y.; and Pia Chamberlain of San Jose, Calif.; and son Darol of Ithaca, N.Y. He also is survived by step-daughters Mary Pugh of Toronto, Canada, and Anne Pugh of Oakland, Calif., plus step-son David Arathorn of Bozeman, Mont., through Chamberlain's second wife, June Steingart Greenfield, who died in 1991.

Funeral and memorial arrangements are pending.