UC Berkeley Press Release

River pioneer and environmentalist Luna Leopold has died at 90

BERKELEY – University of California, Berkeley, hydrologist Luna Bergere Leopold, a giant in the field of river studies who had a profound influence on nationwide efforts to restore and protect rivers and daylight urban creeks, died Thursday, Feb. 23, at the age of 90.

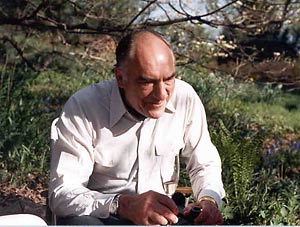

Luna Leopold in his 50s on the bank of the East Fork River near Boulder, Wyoming, attired in his typical Stetson Silverbelly Rancher, Filson cruiser coat and gloves. Leopold and colleague William Emmett conducted bedload research along the river from 1967 through 1980. (Photo circa 1974) |

Leopold, a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of earth and planetary science and of landscape architecture, succumbed to heart and lung failure at his home in Berkeley.

The son of famed environmentalist Aldo Leopold, who often was called the father of wildlife ecology, Leopold was the first to turn a scientific eye on rivers and streams and draw conclusions about their form and evolution. Long before fractals became an everyday word, he realized the similarity between large- and small-scale characteristics of streams.

"He made crucial discoveries about the nature of rivers, especially their remarkable regularity," said William Dietrich, a UC Berkeley colleague of Leopold's and a professor of earth and planetary science. "He showed that this regularity of form applies to all rivers, whether they are in sand boxes or draining entire continents, at scales of a laboratory flume or the Gulf Stream."

Leopold was a "quantifier" who took notes on the natural world and wrote papers on everything from Hawaiian dew to energy expenditures in rivers, and even on the esthetic value of rivers, said Dietrich.

"He was a clear voice and advocate for ethics in science and a defender of the value of esthetics as a reason to protect the natural world, even going so far as to propose a quantification of esthetics," he said.

Leopold developed his expertise during a 22-year career with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), rising eventually to the level of chief hydrologist of the Water Resources Division.

"In effect, Luna turned the hydrologic division of the USGS into a premier research organization, contributing to the prominence the field now has," Dietrich said.

Luna Leopold in the 1980s, celebrating with pipe and champagne. (Photo by Barbara Beck [Nelson] Leopold) |

It was during this time that Leopold was asked to assess plans for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, and after flying the entire length of the proposed route, he reported to his superiors the potential for disaster if they laid pipe on frozen ground and across rivers. His complaints about the inadequacy of planning documents for the pipeline delayed a permit for several years while the pipeline consortium dealt with these issues.

He also was consulted on disputes over Colorado River water allocations and plans for a south Florida jetport.

"In 1969, he practically invented the Environmental Impact Statement through its design and early application to problems such as the proposed Trans-Alaska Pipeline and Everglades Jetport," wrote Thomas Dunne, a colleague of Leopold's who is a professor of environmental science and management and of earth science at UC Santa Barbara. "It can be fairly said that Luna Leopold has changed the way this society approaches environmental problems and conducts environmental science in the service of people and the natural environment."

Leopold launched a second career as a teacher upon arriving at UC Berkeley in 1972, joining his brother, the late A. Starker Leopold, who was a wildlife ecologist and professor of zoology and forestry.

"Put simply, Luna inspired," Dietrich said." His passion about science and his joy about the natural world were felt by students. He strongly believed that simple, systematic observations of natural processes - and the keeping of good field notes - would reveal how nature worked and was a powerful tool in the fight for the environment."

Part of Leopold's educational efforts involved writing lay books that have inspired many, among them "Water: A Primer" (1974) and "A View of the River" (1994), not to mention his seminal book, "Fluvial Processes in Geomorphology" (1964), still a must-read for its eloquence and insight, according to Dietrich.

Leopold was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on Oct. 8, 1915, the son of Estella Bergere, who came from a prominent and colorful New Mexican family, the Lunas, and Aldo Leopold.

According to Leopold's family, "This Santa Fe connection expressed itself throughout his life - in his Spanish guitar music, his interest in the American Southwest, and his love of Navajo silver. From his father, Luna learned the value of observation and careful fieldwork, keeping a journal, good writing, and Dutch oven cooking."

He and his family subsequently moved to Wisconsin, where on weekends he tramped the sandy bottomlands of the Wisconsin River, living a childhood filled with "the kind of freedom (that) would be rare today," he wrote two years ago. He built furniture, fireplaces and cabins. He hunted and fished, made his own tackle and bowstrings, rode horses, composed music for piano and guitar, flew planes, skate-sailed, canoed, skied, painted landscapes, wrote poetry, bound books and acted on stage.

After high school, he entered the University of Wisconsin, graduating in 1936 with a degree in civil engineering. His first job as an engineer with the Soil Conservation Service brought him into contact with problems of water science in the developing field of hydrology. When World War II began, he joined the Army Air Force Corps of Engineers as a cadet, training in physics and meteorology at UCLA, where he obtained a master's degree in 1944. He left the U.S. Army Weather Service in 1946 as a captain.

That experience resulted in a job offer to be chief meteorologist in the Hawaiian Pineapple Institute, where he developed a long-range weather forecasting system for the pineapple and sugar cane plantations in Hawaii. In 1950, he joined the USGS as a hydraulic engineer, and that same year, on a five-month leave from the survey, obtained his Ph.D. in geology from Harvard University.

Early in his more than two decades with the USGS, he discovered, with colleague Tom Maddock, that river width, depth and velocity increase at a similar rate for nearly all rivers as the discharge increases downstream. This discovery has led to more than 50 years of research about the cause of this relationship, and has been essential to theoretical and practical studies of rivers.

While his research focused on rivers in the American West, he traveled widely in Europe, the Middle East, India and Russia, writing about the nature of rivers and streams, the problems of water and sediment supply, flood control, climate change, environmental planning, ecological restoration, scientific ethics, and the broader relationship between people and nature. This research led to quantitative explanations for the natural form of rivers. He published almost 200 scholarly papers and numerous books during a career that spanned 68 years.

He came to UC Berkeley in 1972 and retired in 1986, having served as chair of the geology and geophysics department in his final year. He continued his research and writing, and spent much of the year in Pinedale, Wyo., where he had built a cabin. He taught at the Teton Science School in nearby Jackson.

"His most lasting accomplishment will probably be the huge number of people, both within science and in other intellectual pursuits from government to literature, whom he has motivated to develop and promote environmental science and to absorb it into the 'natural way of doing things' so that it is enduring and committed to human welfare," Dunne wrote of Leopold.

Leopold was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and recipient of the 1991 National Medal of Science. Among his other awards were honorary degrees from six universities and the Penrose Medal of the Geological Society of America, as well as the Warren Prize of the National Academy of Sciences and the Busk Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

In early March, he and M. Gordon Wolman of The Johns Hopkins University received an award, the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Earth and Environmental Science, from the Philadelphia-based Franklin Institute. The posthumous award was "for advancing our understanding of how natural and human activities influence landscapes, especially for the first comprehensive explanation of why rivers have different forms and how floodplains develop. Their contributions form the basis of modern water resource management and environmental assessment."

Leopold was preceded in death by his wife of 30 years, Barbara Beck (Nelson) Leopold, who died in 2004. He is survived by his first wife, Carolyn Leopold Michaels of Rockville, Md., and four children - Bruce Leopold of Baltimore, Md.; Madelyn Leopold of Madison, Wisc.; stepson T. Leverett Nelson of Chicago; and stepdaughter Carolyn T. Nelson of Madison. He also leaves behind three siblings - Nina Leopold Bradley of Baraboo, Wisc.; A. Carl Leopold of Ithaca, N.Y.; and Estella B. Leopold of Seattle, Wash. His brother, A. Starker Leopold, died in 1983.

Memorials may be sent to the Luna B. Leopold Geomorphology Fund, University of Wisconsin Foundation, P.O. Box 8860, Madison, WI 53708-9960, or to the Aldo Leopold Foundation, http://www.aldoleopold.org.

A memorial celebration is being planned at UC Berkeley for late spring. Details will be posted at: http://eps.berkeley.edu/people/lunaleopold/, where copies of many of his papers can also be found.