UC Berkeley Press Release

|

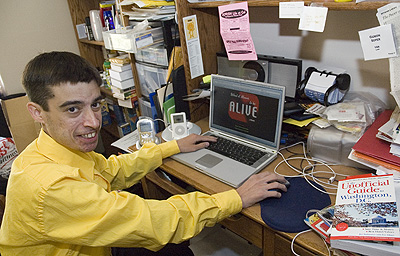

Gideon

Sofer in his room at International

House, showing off one of the two websites he

has built to publicize his Inflammatory

Bowel Disease Stamp Campaign. (Photos by Bonnie Powell / UC Berkeley) |

Student to make stamp pitch to US postmaster

| Sofer on NPR |

BERKELEY – Gideon Sofer didn't ask for a trip to Disneyland or a shopping spree when he made New Jersey's Make-a-Wish Foundation list of terminally ill recipients in 2002. Instead, he wished for a meeting with the U.S. postmaster general.

His goal was a postage stamp to highlight Inflammatory Bowel Disease, which includes Crohn's disease, a chronic intestinal disorder that has landed him in the hospital for months at a time since the age of 12, and led to the removal of nearly half his gut. To date, there is no known cause or cure for the disease.

Tomorrow (Thursday, May 25), the 21-year-old avid stamp collector, who just finished his first semester at the University of California, Berkeley, will get his wish. He is scheduled to meet with U.S. Postmaster General John Potter at 11 a.m. (EDT) in Washington, D.C.

'This disease isn't a sexy subject, but it's got to be talked about. It's time for the suffering to end.' -Gideon

Sofer |

Sofer, who was drawn to UC Berkeley because of its strong disability rights movement, acknowledges that a digestive tract disease doesn't exactly make for ideal dinner table conversation or evoke pretty visuals for a stamp. But that shouldn't stop it from receiving serious consideration, he said.

The U.S. Postal Service has issued stamps to raise awareness or money for breast cancer, AIDS, prostate cancer, organ and tissue donation, diabetes and sickle cell anemia. So why not Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)?

"This disease isn't a sexy subject, but it's got to be talked about," Sofer said. "It's time for the suffering to end."

The opportunity first presented itself to Sofer when he was a New Jersey high school sophomore whose body was wasting away from the disease. When the Make-a-Wish Foundation contacted him, he said he'd call back when he wasn't feeling so lousy.

In the meantime, he thought about asking for a meeting with rock legend Bruce Springsteen or with actor Michael J. Fox, who has battled Parkinson's disease. But he needed something that would make a bigger impact on the lives of IBD sufferers like himself.

Two years later, he figured it out. He wished to see IBD join the pantheon of medical frontier postage stamps, and to do that, he needed the approval of the U.S. postmaster general. Thus, preparations for a meeting began.

Of course, he realizes that meeting the postmaster general doesn't guarantee a stamp. Of tens of thousands of proposals made each year to the U.S. Postal Service's Citizens' Stamp Advisory Committee — which counts former UC Berkeley Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman among its members — only about 20 are accepted. The stamp advisory committee reviews ideas for new stamps proposed by members of the public and then recommends subjects and designs to the postmaster general.

Still, Sofer has garnered plenty of support for his campaign, including the backing of his New Jersey congressman, U.S. Rep. Frank Pallone Jr., who recently introduced a resolution urging a commemorative IBD postage stamp. And through Sofer's IBDCURE Foundation, he's collected 5,000 signatures in an online petition to the Citizens' Stamp Advisory Committee in support of the stamp.

"Gideon refuses to be defeated by his Crohn's disease," said Heyman, a law professor at UC Berkeley's School of Law (Boalt Hall). "Rather, he is successfully informing the world of its nature in a persistent, sophisticated and successful way."

There are regular commemorative postage stamps, which raise awareness of an issue, and semipostal stamps, whose sales generate funds for research or charity. Naturally, Sofer would prefer a semipostal IBD stamp, but would be happy with either.

Not to be confused with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Inflammatory Bowel Disease — which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis — is said to affect 1 million Americans, including 100,000 children and teenagers whose growth it can stunt. It is classified as an autoimmune disorder, although not enough research has been done to confirm this.

It typically begins with inflammation in the intestine, rectum or stomach. Common symptoms are diarrhea, abdominal cramping, rectal bleeding and weight loss. It is uncertain what triggers the inflammation. Theories range from viruses or bacteria inflaming the digestive tract to a person's immune system being unable to recognize certain proteins, and fighting off what it deems as abnormal proteins.

Ever sickly as a child, Sofer was diagnosed with Crohn's disease when he was 12 years old. He has spent much of his life in hospitals and became known around school as a "children's hospital frequent flyer." At first, physicians had no clue what was wrong with him, but his mother kept pushing for help, insisting he was seriously ill.

As it turned out, she was right.

In 2003, he was accepted to UC Berkeley, but had to delay enrolling because the disease got so bad during his senior year at Highland Park High School in New Jersey that he was once again admitted to the hospital. To get the care he needed, he was transferred to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

The inflammation had caused parts of his intestinal walls to narrow, blocking the flow of nutrients and digestive fluids and causing infection. That required surgery to remove 40 percent of his intestine. At one point, he was down to 75 pounds.

"Three days after graduation, I landed in the hospital for six months," Sofer said. "I felt like a 90-year-old man instead of a 19-year-old, it was so physically debilitating. I spent two years recovering and getting my life back ... Spiritually, I was a wreck." He said it hurt just to drink a glass of water.

But he never gave up his plan to get to Cal, and was given a special dispensation to postpone enrollment.

"He called me every couple of weeks or months from the hospital, and talked to me about his strategies to get here," said Ileana Dorn, a supervisor in the UC Berkeley Office of Undergraduate Admissions who was assigned to Sofer's case. "We don't usually postpone admission for that long, but his was such a compelling situation that I really went to bat for him."

Indeed, everything is finally falling into place for Sofer, who has clearly been through hell.

Sofer lives at International House on campus and studies public health and public policy. He has resumed jogging, is off the steroidal medication he once took, and is on a strict high-protein diet that excludes wheat, gluten and dairy products, which can trigger inflammation.

He still gets visits from a nurse, has his blood tested regularly, and self-administers IV infusions of fluid so he doesn't get dehydrated.

"I have so much of my life back," said Sofer, who is thrilled to be living in Berkeley, which he calls "the health food capital of the world," and hopes to take a class with UC Berkeley food and nutrition journalist Michael Pollan.

Indeed, at this point, nothing would make him happier than to see a stamp highlighting the disease that paralyzed him at a time when he should have been playing sports and dating. But it is also a disease that has made him wise beyond his years, giving him rare insight into what it means to be alive.

"If I were not to live much longer, I would be at peace with myself, knowing I had done everything in my power to conquer this disease," he said.