UC Berkeley Press Release

Telemedicine eye care benefits state's underserved residents

BERKELEY – Armed with new telemedicine software, optometrists at the University of California, Berkeley, are working with doctors at community clinics throughout California's Central Valley to provide eye exams for thousands of low income diabetic patients.

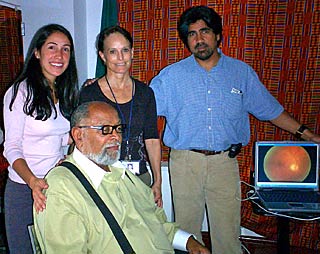

Gathered around a computer image of the Rev. Cecil William's retina are, from left, UC Berkeley optometry student Andrea Buitrago, Williams, Glide Health Services medical director Dianne Budd, and UC Berkeley optometry professor Jorge Cuadros. Williams, leader of Glide Memorial Church, was one of 15 patients Cuadros screened for diabetic retinopathy at Glide Health Services in San Francisco in July. (Alberto Cuadros photo) |

Latinos - who make up 40 percent of the population in the Central Valley - are expected to be the principal beneficiaries of this pilot project. With a rate of diabetes that is nearly three times as high as that of the general population of the United States, this group is at particularly high risk for diabetic retinopathy, a sight-threatening side effect of the disease, said Jorge Cuadros, the project's director.

Since September 2005, when the project was launched, 13 clinics have received retinal cameras and an open-source image management program developed at UC Berkeley's School of Optometry for storing and transmitting patient information and diagnostic images. The equipment allows doctors to take high-resolution photos of patients' retinas and send them electronically to optometrists at UC Berkeley for interpretation and diagnosis.

"We're finding sight-threatening retinopathy in about 10 percent of the patients," said Cuadros, a clinical professor of optometry at the school and the driving force behind the project. "Without this new system, most of these patients would have fallen through the cracks. They would have ended up at an eye care provider's office once they lost vision in an eye, instead of being diagnosed early on, when preventive measures can still help"

Diabetic retinopathy is the main cause of permanent blindness in working-age adults, Cuadros said. Annual eye exams are a crucial component of care for diabetes patients, yet less than half the people who should get exams do, he said. Low income Latinos in the Central Valley are even less likely to obtain the required care. "There are so many barriers," Cuadros said, "like economics, language or no transportation to a specialist's office that may be in another town miles away."

Most low income residents of the Central Valley go to community clinics for their general health care, but few clinics have the equipment or expertise to screen for vision problems. In 2003, Cuadros decided to address this problem as the research arm of his work toward a Ph.D. in medical informatics.

"The idea was to be able to set up a program where sight-threatening retinopathy could be detected in the clinic at the same time that patients were going for their medical visit," he said. "I knew that we had the technology to address this via telemedicine, but the challenge was to do it in a way that was economically sustainable."

At the heart of Cuadros's solution are three components: EyePACS, a license-free, Web-based system he developed over the last five years to send, store and display eye-related patient information, images and diagnostic data; his colleagues at UC Berkeley's School of Optometry, who volunteered to read the retinal images sent to them from the clinics; and new legislation, California Assembly Bill 354, that went into effect July 1. The bill permits Medi-Cal reimbursement for doctors who review dermatology or ophthalmology records that have been sent and stored electronically.

With a $630,000 grant from the California Endowment through the California Telemedicine and eHealth Center and the California Health Care Foundation, Cuadros has equipped the 13 rural clinics in the project with EyePACS and retinal cameras and has provided training in their use to doctors and other clinic staff.

In September 2005, the Golden Valley Health Center, in the city of Merced, was the first clinic to start the project. In June 2006, Family Practice Associates, a clinic in Oroville sponsored by the Oroville Hospital, became the thirteenth. About 40 patients a week are being screened now at all the clinics, but once staff become comfortable with their new equipment and procedures, Cuadros said, he expects that each clinic will screen about 1,000 patients per year.

Until now, optometrists at UC Berkeley have been reading free of charge the detailed retinal images that the clinics are sending to them. But with the enactment of AB 354, the clinics will now be paid by Medi-Cal for enough cases to sustain the programs. Until the bill went into effect, Medi-Cal would reimburse only for dermatology and ophthalmology services rendered via telemedicine when doctors and patients "met" face to face through Web cameras. Now, using Cuadros's EyePAC data storage system, doctors can examine records without the patient being present in real time, and be reimbursed for the service. This system will greatly expand the use of telemedicine in California for vision care, Cuadros said.

From the outset, the project has been paying off. Hundreds of cases of diabetic retinopathy in every stage have been diagnosed, and other health problems have been discovered as well. One example is the case of 40-year-old Michael Cheng Thao, a Merced resident who had been seeing a doctor in town about his headaches. After running various tests, the doctor scheduled an appointment for Thao with a local ophthalmologist for two months later, the first available opening. In the meantime, at his cousin's suggestion, Thao visited Golden Valley Health Center in May for retinal screening. The image was sent to Cuadros in Berkeley, who reviewed it within the hour. When he noticed that both of Thao's optic nerves were swollen, Cuadros immediately called the clinic: The swelling could be a sign of a life-threatening condition. Three days later, Thao underwent surgery for a non-malignant brain tumor.

The retinal cameras are also impacting health care in unexpected ways, Cuadros said. "When clinic doctors look at the blood vessels in the retinal images, they get really excited because they are looking directly at the microvascular system of the human body," he said. "This is something a family practice doctor usually doesn't get to see." If the arteries in the retina are diseased, the rest of the vascular system probably is, too, he added.

The images are making doctors and their patients pay attention. When a 34-year-old woman was shown the lesions in her retinal vessels - the first signs of retinopathy - she finally started taking steps to control her diabetes, including taking the insulin she had earlier resisted, Cuadros said.

The EyePACS system that Cuadros developed is what is known as a "picture archiving and communication system," or PACS. Working with Wyatt Tellis, a staff research scientist in the UC San Francisco Department of Radiology, Cuadros based his system on simple components for transmitting secure information and tailored it for retinal imaging. To spare clinics from paying thousands of dollars in licensing fees, the team built EyePACS on an open-source platform, incorporating various components, such as FreeBSD and PostgreSQL, that UC Berkeley's computer science department had helped to develop over the years.

The server that hosts the EyePACS system is big enough to accommodate all of the 600 or so community clinics in California, Cuadros said.

Cuadros is now working on a variety of projects that are expanding the scope of the telemedicine system. He's creating the software and training program that will allow it to be used to examine glaucoma and other diseases, and he's in the process of developing affordable retinal cameras, hoping to lower their price from $20,000 to $5,000.

He's also establishing mobile screening clinics, taking retinal cameras to community centers and other places where needy patients can be examined on the spot. Last month, he spent an afternoon at Glide Health Services in San Francisco's Tenderloin District and screened 15 diabetes patients there, including Glide Memorial Church's long-time pastor, the Rev. Cecil Williams.

And Cuadros has extended the reach of the project far beyond California's borders. Last year, he partnered with Vision For All, Inc., a non-profit organization that provides eye care to people in need. He traveled with George Bresnick, medical director, and Geri Hendrickson, executive director, to Guanajuato, Mexico, where they worked with Mexican doctors to develop a diabetic retinopathy detection program. They have embarked on an ambitious program to screen every diabetic patient in the region starting in July with the 1,200 patients in the town of San Felipe. Cuadros and Bresnick have already reviewed the first 300 retinal images sent to them by EyePACS from the Mexican health team and will work with the project through its duration.

"So often new technology broadens the gap between rich and poor," Cuadros said. "So it's particularly satisfying in this case to be able to minimize health disparities using technology and at the same time to evolve new ways to deliver health care."