UC Berkeley Press Release

|

George Smoot enjoys the accolades at an LBNL news conference Tuesday honoring his selection as winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in physics. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

UC Berkeley, LBNL cosmologist George F. Smoot awarded 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics

BERKELEY – Cosmologist George F. Smoot, who led a team that obtained the first images of the infant universe — findings that confirmed the predictions of the Big Bang theory — won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics today (Tuesday, Oct. 3).

|

• Photos and George Smoot's lecture at December, 2006 Nobel festivities in Sweden |

Smoot, a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and an astrophysicist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), shares the prize with John C. Mather of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. This is UC Berkeley's 20th Nobel Prize since Ernest O. Lawrence won in 1939, and its eighth physics Nobel.

Smoot, a resident of Berkeley, said the early morning call today from Sweden announcing the prize caught him off guard — the Nobel Committee for Physics had obtained his unlisted cell phone number by waking his neighbor.

"There were no rumors," said Smoot, 61. Though he got two calls from Sweden congratulating him on winning, he said, "I wasn't absolutely sure until I ran to my computer and pulled up the Nobel Web page. Then I believed it."

UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Birgeneau hailed Smoot's achievement, saying, "There are few more exciting moments than this in the life of a university — I know the entire campus community is enormously proud of George's achievement and joins me in sending him hearty congratulations."

Joining in the congratulations was fellow Nobelist Charles Townes. "It's very well justified," said Townes, a professor in the graduate school who won the physics prize in 1964. "He's discovered much about the origins of the universe, and what can be more important than that?"

'Human beings have had the audacity to conceive a theory of creation and now, we are able to test that theory.' -George F. Smoot |

In 1989, Smoot and Mather, who earned his Ph.D. in physics from UC Berkeley in 1974, together led the building and launch of NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite to look for telltale signs of the primordial explosion. According to theory, the Big Bang fireball 13.7 billion years ago filled the universe with heat that has since cooled to a mere 2.7 degrees above absolute zero.

They announced in 1992 the discovery of residual heat from the explosion, as well as minute variations in temperature across the sky that indicated the beginnings of structure in the early universe that evolved into galaxies and clusters of galaxies.

"Those measurements really confirmed our picture of the Big Bang," Smoot said. "By studying the fluctuations in the microwave background, we found a tool that allowed us to explore the early universe, to see how it evolved and what it's made of."

During the last 34 years, Smoot, who has been a UC Berkeley physics professor since 1994 and an astrophysicist at LBNL since 1974, has led a succession of projects that have helped change the nature of the quest to understand the origin and evolution of the universe.

"Although cosmology has been around since the time of the ancients, historically it has been dominated by theory and speculation," Smoot said. "Very recently, the era of speculation has given way to a time of science. The advance of knowledge and of scientific ingenuity means that at long last, we can actually test our theories."

In 1974, Smoot submitted a satellite proposal to NASA to search for, measure and map tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. Fifteen years later, working with COBE project director John Mather, the COBE satellite was launched, joining a competitive quest that at that stage involved many scientific teams.

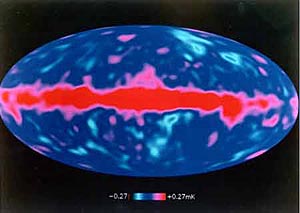

This map of the ancient sky shows the minute variations in temperature and density discovered by the team led by astrophysicist George Smoot. Over billions of years, gravity magnified these small differences into the clusters of galaxies we observe today. (COBE Project) |

In April 1992, Smoot's team - his group involved more than 40 people, and the COBE satellite project an estimated 1,000 individuals - announced it had found what had evaded scientists for decades: colossal hot and cold regions of differing densities in the infant universe.

In announcing the discovery that same year at an American Physical Society meeting in Washington, D.C., Smoot said that these regions, 14-billion-year-old fossil relics from the primeval explosion, grew into the galaxies and superclusters of galaxies evident today.

Smoot said the COBE maps depicted the universe as it looked when it was about one-ten-thousandth of its current age, or about 300,000 years after its birth.

These COBE results have been confirmed by subsequent balloon experiments, including the UC Berkeley-led Millimeter Anisotropy eXperiment IMaging Array (MAXIMA) experiment and its southern complement, Balloon Observations Of Millimetric Extragalactic Radiation and Geophysics (BOOMERANG), and more recently by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). Smoot, who collaborated on those experiments, is now involved with the European Space Agency's Planck satellite, scheduled to launch in 2008.

The COBE team that Smoot headed involved participants from UC Berkeley, LBNL, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, UCLA, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Princeton University. In addition to Smoot, team members at LBNL included astrophysicist Giovanni De Amici, data analyst Jon Aymon, and UC Berkeley graduate students Charley Lineweaver and Luis Tenorio.

After meeting the press indoors at LBNL, Smoot undergoes another round of photos and questions on a walkway overlooking campus and the bay. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

Smoot was born in Yukon, Fla. His father was a hydrologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, his mother was a science teacher and school principal. Smoot received his Ph.D. in physics from MIT in 1970 and decided to enter the field of cosmology, believing it was a frontier of fundamental science that was ripe for exploration.

At the time, said Smoot, cosmology was a "fringe field. Back then, you could get all of us in the field into a single room. I remember the teasing from my particle physics colleagues that real physics is done at accelerators. Today, opinions have changed. We have begun to explore the early universe, the original accelerator. The fields of particle physics and cosmology have been joined."

UC Berkeley has had a long history of Nobel winners in physics and chemistry, though the campus's most recent Nobels - in 1994, 2000 and 2001 - have been in economics.