UC Berkeley Press Release

|

UC

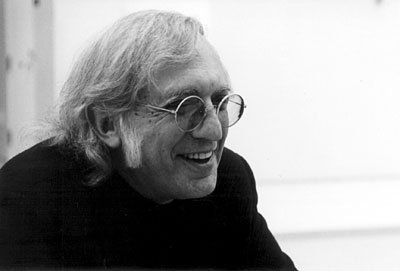

Berkeley history professor Lawrence Levine. (Bruce

Jackson photo) |

Lawrence Levine, esteemed history scholar, dies at age 73

BERKELEY – Lawrence W. Levine, a highly influential history professor for more than three decades at the University of California, Berkeley, died on Monday (Oct. 23) of cancer at his home in Berkeley. He was 73.

Through his writings and teaching, colleagues said, Levine helped transform cultural history in the United States into a vibrant and accessible field of study. A champion of multiculturalism, Levine won a MacArthur "genius" fellowship in 1983 for his intellectual curiosity and scholarship.

In "Black Culture and Black Consciousness" (1977), Levine's best known work, he made use of the oral expressive tradition of African Americans to examine how they perceived themselves, their position in American society, and their relations with whites.

According to UC Berkeley history professors Leon Litwack and Waldo Martin, the book was a pathbreaking study of folk thought and culture that exerted an extraordinary influence on several generations of scholars - not only historians, but anthropologists, folklorists, musicologists, sociologists, and students of American and African American culture.

Historian Shane White, a professor in Australia at the University of Sydney, where Levine once taught as a visiting professor, added that Levine was "one of the best historians writing in the second half of the 20th century. His pioneering explorations of the American past made possible the current explosion in the popularity of cultural history."

Levine's 1988 book "Highbrow/Lowbrow" and the 1993 book "The Unpredictable Past" demonstrated not only the varieties of historical consciousness and documentation, but the interplay of American thought and behavior in folk and popular culture. And "The Opening of the American Mind," a 1996 book, was a spirited defense of multiculturalism and a powerful critique of conservative critics of modern American culture.

In a 1996 interview with The New York Times, Levine said that in "The Opening of the American Mind," he tried to show "that the genius of America has been its ability to renew its essential spirit by admitting a constant infusion of different people who demand that the ideals and principles embodied in the Constitution be put into practice. The result has been to open America to great diversity..."

UC Berkeley's Martin said Levine "was a great historian who revolutionized American cultural history. He also was a great friend."

Said Lily Wong Fillmore, a professor emerita in UC Berkeley's Graduate School of Education, "He educated all of us about American cultural history, and he taught me the meaning of the expression 'mensch' - he was truly a person of integrity, good humor and honor."

Fillmore and Levine were on a committee in the 1980s that developed a campus requirement that all new undergraduates take a class on America's complex racial and ethnic past and present.

Levine was born on Feb. 27, 1933, and raised in New York City He received his bachelor's degree in 1955 in history from the City University of New York and his master's and doctorate degrees in history from Columbia University in 1957 and 1962, respectively.

He told The New York Times that before going on to graduate school, his history teachings had been limited. He said he knew "very little about the majority of the people in the world. We studied Northern and Western Europe. Nothing in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Even Canada was a great blank. My own father was an immigrant from Lithuania, and my grandparents were from Odessa, but we talked only about Northern and Western Europe. There's something wrong with that."

Levine joined the UC Berkeley faculty in 1962, retiring in 1994 as the Margaret Byrne Professor of History. Also in 1994, he was appointed professor of history and cultural studies at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va.

While on the UC Berkeley faculty in the 1960s, Levine immersed himself in the political life of the campus, participating in sit-in demonstrations by the Congress of Racial Equality, one of the nation's oldest civil rights groups, to force stores to hire black people. He also joined other historians who marched in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

During the Free Speech upheaval at UC Berkeley, he came to the defense of students protesting a ban on political activity on campus, activity in support of the civil rights movement.

In the late 1980s, Levine was a member of the campus Academic Senate's Special Committee on Education and Ethnicity, which developed UC Berkeley's American Cultures Breadth Requirement, first launched in 1991.

The innovative move, which made national headlines, resulted from complaints at the time by students who felt their history wasn't being taught on a campus that was rapidly changing in its ethnic and racial composition. The curricular change became a successful part of the UC Berkeley experience and attracted the attention of educators elsewhere.

Fillmore, who also is UC Berkeley's Jerome A. Hutto Professor of Education emerita, said Levine's contribution to the committee was "crucial: He was a moderating force, reminding the committee about the necessity to be inclusive and interdisciplinary, if the proposal had any chance of winning the support of the Senate faculty. The committee had faculty and student members, and Larry Levine made sure that students' voices were heard and included in the design of the proposal."

Litwack, a close friend of Levine's, said "few individuals I have known in this profession or out of it have been as important to me: as committed, as insightful, as creative, as imaginative, as challenging, as intellectually engaged, as stimulating, as provocative, as tough-minded, as open to new ideas and experiences. He will always be with me in my work and thoughts."

During his 32 years on the faculty, Levine received many honors. Following the MacArthur award, he was elected in 1985 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. And in 1994, he was named a Guggenheim Fellow.

From 1992-93, he served as president of the Organization of American Historians, and he received the 2005 American Historian Association's Award for Scholarly Distinction.

Levine is survived by his wife, Cornelia; stepson, Alexander Pimentel of Richmond; sons, Joshua and Isaac of Berkeley; sister, Linda Brown of New York City; and three grandchildren, Stephanie and Benjamin Pimentel, and Jonah Levine.

In lieu of flowers, the family asks that contributions be made to the American Cancer Society. A memorial service is pending.