UC Berkeley Web Feature

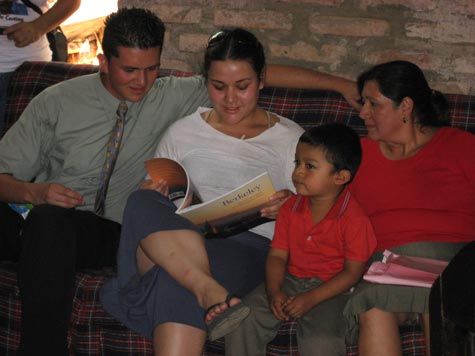

Angela's brother, Henry, her nephew, Hector, and her mother, Blanca, look at a commemorative book about Berkeley. (Eric Stover photo) |

Salvadoran war orphan finds closure through DNA results and family reunion

BERKELEY – Angela Fillingim, one of thousands of children orphaned or adopted during El Salvador's bloody 1980-1992 civil war, shared with reporters on Thursday, Dec. 21, memories and photos of her extraordinary return to her native land. She spoke at a well-attended press conference at UC Berkeley's Human Rights Center, a key collaborator in the DNA Reunification Project, which is helping Salvadoran war orphans track down their biological families.

Angela with her brother and mother. (Liz Barnert photo) |

Fillingim, 21, was adopted as an infant from El Salvador by a Berkeley couple in 1985. She recently received confirmation of her parentage after providing a DNA sample to the database, which was developed by UC Berkeley's Human Rights Center, the California Department of Justice and the Boston-based Physicians for Human Rights.

On Saturday, Dec. 16, at her biological grandparents' modest ranch in Ilobasco, a town in north central El Salvador, she met her biological mother, half-brother, grandparents, uncles and nephews. It had been a year and a half since she began the search.

"I felt a sense of relief. It was a nice moment to be on that ranch and hear all the stories," said Fillingim, a UC Davis sociology student. She said her biological mother, Blanca Rodriguez, cried when she saw the daughter she had given up for adoption because of violence and poverty in El Salvador.

"She asked me to forgive her," Fillingim said. But, instead, Fillingim wanted to thank her. "I've had such a great life," she said. "I thanked her for making the best possible decision she could make . under the circumstances."

Untold numbers of babies and youngsters were snatched by soldiers from their families - in some cases as war trophies - during military sweeps to wipe out leftist guerilla sympathizers during the armed conflict. Some were raised on military bases. Others were placed in orphanages or foster homes. Many of the younger ones were adopted by families in the United States and Europe who were led to believe the children had been orphaned by the war or abandoned by their parents.

Today, "many of those families live in a limbo of hope and despair. They don't know what has happened to these children," said Eric Stover, director of the Human Rights Center, and co-founder of the DNA Reunification Project.

Stover had already worked on the search for Argentina's missing children when he was contacted in 1994 by Father Jon de Cortina, co-founder of Asociación Pro-Búsqueda de Niñas y Niños Desaparecidos (Search for the Missing Children) in El Salvador. At the time, Stover was executive director of Physicians for Human Rights. He brought the missing children project with him when he joined UC Berkeley in 1996.

The response to the project from families in El Salvador has been overwhelming.

"There is no stronger human force on earth than a father or mother looking for their missing child," Stover said at the press conference.

However, he said, there is still much outreach to be done.

"We want to expand on our operation," Stover said. "We now need to go out and find the children who have been adopted."

As of October, Stover said, there were 784 requests from Salvadoran families looking for missing children, 316 resolved cases, 182 reunions or reencuentros facilitated by Pro-Busqueda, and 95 orphans or adoptees still actively looking for their biological families.

Charles Brenner, a forensic mathematician who provided software for the DNA database and worked on the project as a volunteer, said at the press conference that he believes that as many as 10,000 children could have been orphaned by the war, based on adoption visas issued by the U.S. State Department, among other factors.

Brenner talked about the case of a young man in El Salvador who, at age 8, heard from his neighbors that he was adopted. When he confronted his adoptive parents, they avoided the subject. He later contacted Pro-Busqueda, which began a search. The group tracked down his biological family, but the family only reported two missing daughters. Later, the family recalled that there had been a son, but he had been presumed dead because he had been an infant in his mother's arms when she was shot dead. Little did they know that he had been taken by the soldiers and grew up in a Salvadoran military family. His adoptive family, it turned out, was linked to the death of his mother and his separation from his biological family.

Fillingim is among the luckier ones. Her adoptive parents, both social workers in Berkeley, had always supported her efforts to trace her roots. She visited Pro Búsqueda during a summer trip to El Salvador in 2005. Early in 2006, she learned of Blanca Rodriguez through an adoption paper trail. After DNA results confirmed that maternal relationship, Fillingim made arrangements to visit her biological family for the first time, although she had already exchanged e-mails and letters with them.

During her visit to El Salvador, Fillingim said, she learned that her biological mother and father met at a restaurant and dated. At the time, her father was either a civil engineer or a student of civil engineering. After the couple broke up, Blanca Rodriguez learned she was pregnant. She tried to track down the father, but could not find him. She suspected he had left the country. And since then, no contact has been established with him.

"My mother was working in a sweat shop, and she could not afford to raise a child. She didn't have the support of her family as an unwed mother," Fillingim said. "She really felt that (adoption) was the best option, given the circumstances of the political and economic situation."

Today, Fillingim said, her biological mother and half-brother Henry, 17, live in Soyapongo, an area that is ridden with poverty and gang violence. She said her brother was so protective of her during the visit that he followed her around with an umbrella so she would not be burned by the sun. His father was killed in the continuing violence in El Salvador.

She said she has come home with a lot of beautiful memories. Her adoptive father, Jerry Fillingim, said he and his wife, Greta, continue to support their daughter's effort to get to know her biological family.

"Nobody can have too much support and too much love," Jerry Fillingim said.

As for Angela Fillingim, she feels incredible peace.

"A lot of people haven't had this chance to have closure," she said. "It's an amazing feeling."