UC Berkeley Web Feature

|

Forum participants from right to left: Steven Chu, George Smoot, Charles Townes, Daniel McFadden, Yuan T. Lee, Donald Glaser, and Chancellor Robert Birgeneau. (Peg Skorpinski photos) |

"There is no time": Six Nobel Laureates say averting world's climate crisis requires immediate energy research, conservation, and regulation

BERKELEY – Last week, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock two minutes forward, to five minutes to midnight. Created in 1947 by former Manhattan Project scientists, the clock is a simple metaphor for how close humanity is to self-annihilation. The latest adjustment was made in response to the global failure to address nuclear weapons and — for the first time — a non-nuclear-related issue: the climate crisis.

Both climate change and nuclear power, in its more benign form as an energy source, were touched on repeatedly during the sold-out "Energy Self-Sufficiency in the 21st Century" colloquium featuring six of the seven Nobel Laureates currently on UC Berkeley's faculty. The forum's participants agreed that inaction will indeed result in apocalypse — but also that humanity's prospects are far from hopeless, if we act now.

Cleaning up our energy act

| About Discover Cal This series seeks to bring the intellectual richness of UC Berkeley to Cal alumni and parents. Schedule of lectures |

Chancellor Robert J. Birgeneau introduced the Jan. 20 forum, which kicked off the Northern California portion of the UC Berkeley's Discover Cal series. All over campus, researchers are intently focused on energy topics, Birgeneau said. Berkeley has joined with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in a bid to win a $500 million grant from the British Petroleum Energy Biosciences Institute for long-term research into the production of alternative fuels.

Steven Chu, winner of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics, began by saying he wanted to insert the word "clean" into the program's title, to make it "Clean Energy Self-Sufficiency in the 21st Century" — referring to forms of energy that are carbon-neutral, not contributing to greenhouse gases.

'What does this really mean? The water storage in California is at risk in the least alarmist model, and one that I personally think is way over-optimistic. This is going to happen all over the world. In the most alarmist model, we're going to have a serious drinking water problem; forget agriculture.' -Steven

Chu |

Self-sufficiency could be achieved simply by "taking coal and liquefying it, but that would be an unmitigated environmental disaster," said Chu, the director of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where he is overseeing groundbreaking research into alternate energy technologies.

"The reason I have become so passionate about the energy problem is the Earth is warming up," he continued. "That's not a matter of debate; it's a matter of measurement."

After taking the audience on a breakneck summary of both the planet's and California's predicament — the risk to the state's water supply posed by global warming — Chu paused, then switched from doomsday scenarios to optimism. "The good news is we can do something about this," he said.

Berkeley Labs' Helios Project and other initiatives are already hard at work on converting solar energy into carbon-neutral forms of transportation fuels. Researchers are exploring how to improve the conversion of plant material into liquid fuels and into the development of a new generation of solar and photovoltaic cells that can more efficiently generate and store electricity.

Chu showed a dramatic slide, of a map of the United States with a tiny square covering a portion of Nevada. With a small amount of desert and photovoltaic cells that were at least 15% efficient — that could convert at least that much of the sun's energy shining down on them into electricity — we could power the entire United States, he said.

The United States already generates some of its own transportation fuel from plant matter in the form of ethanol from fermented corn. However, corn is what is known as an "input-intensive" crop, requiring so much chemical fertilizer and herbicides, plus energy to turn it into fuel, that critics question whether growing it for fuel is actually a net energy loss. Five to ten years from now, Chu promised, researchers will have developed a new set of plants that will make biomass much more economically friendly than current crops. And by studying the lowly microbes living in termites' guts, which are able to convert cellulose into energy on a microscopic level, researchers will be able to convert biomass to fuel much more easily and efficiently.

But for these goals to become reality, Berkeley Labs needs funding, Chu said, concluding his talk with a plea for donations for Helios while the center awaits major grants.

"We want to get started today," he explained. "There is no time."

Self-sufficiency begins at home

The five speakers who followed Chu all agreed that time was of the essence as global temperatures rise, and that a vitally important first step is for all Americans, not just Californians, to embrace energy conservation immediately.

Among all the world's nations, Americans are the biggest energy hogs and the biggest polluters in terms of carbon dioxide emissions, pointed out Charles Townes, winner of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics. "Some of this is because of our great wealth — we just don't care that we use a lot of energy. But a lot of it is because we're not paying attention, and we should," he said. Even a simple choice like the color or roof paint can have far-reaching implications for energy usage, Townes demonstrated. (In contrast to his fellow Nobelists, the nonagenarian Townes illustrated his lecture not with PowerPoint slides, but with old-fashioned overhead transparencies.)

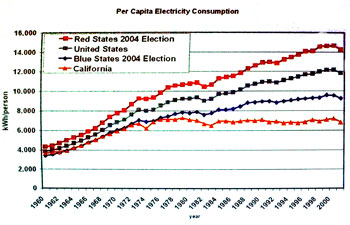

California, as Townes and others mentioned proudly, is way ahead of most U.S. states when it comes to energy conservation, thanks in no small part to the decades-long research and lobbying efforts of Art Rosenfeld, a professor of physics at UC Berkeley and Berkeley Labs. By serving on the state's energy commission and advising its governors, including Davis and Schwarzenegger, Rosenfeld has helped ensure that improved efficiency standards for appliances and buildings were integrated into California's codes.

A chart showing California's conservation efforts — in an interesting context — that speaker Daniel McFadden borrowed from Berkeley physics professor Art Rosenfeld. |

"More than any other person, Art Rosenfeld has showed us as a practical matter how we can approach energy self-sufficiency," said Daniel McFadden, winner of the 2000 Economics Prize. At the panel's invitation, Rosenfeld stood up and was applauded by the 900-member audience. (Read more about Rosenfeld's work in the current issue of California magazine.)

Ultimately, the "best answer is to just say no to energy," according to McFadden. Conservation is "the ultimate green renewable energy source. Each BTU freed up through reduction and consumption displaces a BTU of imported fossil fuel and also the capital cost of processing and transporting it."

That's why gains in efficiency have roughly offset gains in income; that is, U.S. energy use per dollar of GDP has actually decreased. Startlingly, improved refrigerator standards alone save more energy every year than is generated by all of the conventional hydropower and renewable energies like wind and solar. And there are other areas crying out for similar improvements, such as fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks, said McFadden, which are set at the national level.

McFadden proposed some concrete economic changes that he thinks would make the U.S. energy self-sufficient by the year 2050:

- A substantial carbon tax that would reduce demand, encourage voluntary conservation, and make fossil fuel prices reflect their true geopolitical and environmental costs,

- Revenue from the carbon tax could finance conservation and renewable energy technologies

- Tradeable CO2 emission licenses to promote the best use of fossil fuels

- Tradeable energy vouchers

Donald Glaser, winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physics, seconded the importance of government regulation. "The free market is a wonderful mechanism, but it often doesn't work," he said. Consumers are often reluctant to pay more up front — say, for an energy-efficient new refrigerator — in exchange for future savings, unless forced to.

More about the participating Nobel Laureates Steven Chu, director of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1997 for developing methods of using laser light to supercool gases and keep the chilled atoms afloat and captured in different kinds of "atom traps." His work allows individual atoms to be studied with great accuracy and their inner structure determined. Professor of the Graduate School Donald Glaser won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1960 for his invention of the bubble chamber, which allowed scientists to track the movement of atomic particles and marked an important step in the exploration of the structure of matter. Professor in the Graduate School Yuan T. Lee took the laser research of his Berkeley colleague Charles Townes (below) steps further, winning the 1986 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work. Lee’s designs and experiments with molecular beam devices sent streams of intensely packed molecules into each other at supersonic speeds. The resulting knowledge has contributed to today’s powerful lasers. Daniel McFadden, the Cox Professor of Economics, won the Prize in Economic Sciences in 2000 for his econometric methods for studying behavioral patterns in individual decision-making. A deep interest in social welfare drives McFadden's research. Applications of his tools include predicting BART’s initial ridership and measuring the economic damage to individuals from an oil spill. Astrophysicist George Smoot won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2006. Smoot headed a team that was able to image the infant universe, revealing its newborn form and the patterns that have shaped the universe ever since. Historically, cosmology had been essentially a theoretical field; Smoot devised ways to conduct experiments that produced data and information about the early universe. Charles Townes, UC Berkeley professor in the Graduate School, won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1964. He began his research into the properties of light after designing radar systems during World War II. His idea for amplifying light into an intense beam led to the development of the laser, a tool that has revolutionized industry, medicine, communications and astronomy. |

We may live in a democracy, but sometimes "governmental regulation is the only way to do some things that we jointly think are important," he urged.

The lowest-hanging fruit on the conservation tree is vehicular fuel efficiency, Glaser argued, but Congress has refused to pluck it. The same has held for subsidies on oil, until very recently. "Yesterday, for the first time, the Democratic Congress reduced the level of subsidies for oil, which will make oil more expensive and give alternative fuels a fighting chance," he said, to cheers.

Rethinking nuclear power

One alternative fuel that George Smoot, winner of last year's Nobel Prize in Physics, would like to see have a fighting chance is already in use, but languishing under a decaying cloud of controversy: nuclear power.

In order to be taken seriously on the subject of nuclear power, he said he would first give a "walk-the-walk talk" about conservation to establish his "bona fides." Smoot, who has been logging his own energy usage for close to 40 years, presented a detailed account of his conservation efforts small and large, from weather stripping windows and changing to compact fluorescent light bulbs (which alone dropped his usage by a third) to installing passive solar heating via a solarium. When he does drive, which is not often, he drives a 1986 Toyota Camry with about 100,000 miles on it. And as if averaging 5,000 miles per year weren’t impressive enough, Smoot felt compelled to add that "I only put about half of them on" – the perpetrator was an ex-girlfriend who commuted to the Peninsula.

Having established that he was not a profligate energy addict looking for a quick and dangerous fix, Smoot turned to the topic of nuclear power. He was on the nuclear reactor safety committee in the '70s, he said, following the national energy crisis of 1973. Shortly after his committee determined that reactors were safe came the Three-Mile Island incident — which killed no one but scared America to pieces — and the Chernobyl meltdown in the Soviet Union, which was vastly more deadly and sealed the deal as far as public perception: No new nuclear reactors for the United States.

'In a sense, what we need to reestablish is the harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, a relationship that became disjointed after the onset of the industrial revolution and when human society became increasingly dependent to the point of addiction to energy from fossil fuels.' -Yuan T.

Lee |

And yet, Smoot pointed out, there are 103 nuclear plants in the United States generating 20% of the nation's total electricity, and more importantly, more than 70% of it is emission-free power. Like it or not for those in the audience — Berkeley is famous for being a "nuclear-free zone" — Smoot argued, "Nuclear energy is one of the ways that we're going to maintain a high standard of living in this country."

That is, if we make nuclear power a national priority as France has. The vast bulk of our existing reactors were built and staffed in the '70s, and as those plants age and their employees approach retirement age, there is no new technology or trained personnel ready to replace them.

Smoot concluded his presentation with suggestions for getting new nuclear power plants online. The first step would be to address public acceptance concerns, followed by developing programs for nuclear engineers and supporting research into improved nuclear technologies. Nuclear "parks" should be set up in remote areas for security. His most controversial suggestion is for the federal government to license only four or five companies to build and operate nuclear power plants — not the 70 or so independent utilities who currently do so — which would vastly improve safety and accountability.

Later in the forum, when the Nobel Laureates had the chance to discuss each others' views, Glaser pointed out that no one had addressed the real problem of nuclear power: storing radioactive waste from reactors.

Jumping in, Chu answered that technologies were in the pipeline that would shorten the radioactive lifetime of that waste from a couple hundred thousand years to a more manageable few centuries, as well as reduce the amount of waste by a factor of 10 to 30. That these technologies are not yet commercially viable is indeed a major roadblock to ramping up nuclear power: "If we continue as we are now, we will have filled up Yucca Mountain [the contested U.S. storage facility for nuclear waste] by 2012," said Chu. "Except we won't have opened Yucca Mountain by 2012."

It takes a global village

While his colleagues debated individual technologies that might lead to energy self-sufficiency for the United States, Yuan T. Lee, winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, delivered a rousing call to action on a global level.

Speaking softly and urgently, using no slides or transparencies, Lee described how fast the earth has devolved in the last few centuries from an unlimited trove of resources to one rapidly approaching an inability to support the entire human population or to digest its waste production. For the first time in history, humanity has been confronted with truly global problems to solve, and it is up to the United States to lead the charge.

Why America? Because this nation is far and away the biggest energy user and polluter, said Lee. And since history has shown that the so-called "developing" countries tend to follow in the footsteps technologically of the "developed" countries, the United States must lead by example: it must create and adopt renewable and clean energy sources as soon as possible, Lee urged, so that they will be available to meet the exploding energy needs of China, India, and South American countries.

If not, the consequences will be dire. "We cannot go on as we have been. Things have to change, and we are the ones who must make it happen," he said. "Not 'we' as in the people up here speaking to you today, but 'we' as in everyone in this room, and everyone walking around outside, and everyone who thinks tomorrow should be a little bit better than today. We have to face the problems from energy use and its impact on our environment."

The clock is ticking.

More resources:

- A complete webcast of the forum is available

- Chancellor Birgeneau announced that the Nobel Laureates will answer all questions that were submitted to the audience; the answers will be published at a later date on the Discover Cal website.

- Explore Berkeley's numerous research and policy initiatives through the campus Energy website