UC Berkeley Web Feature

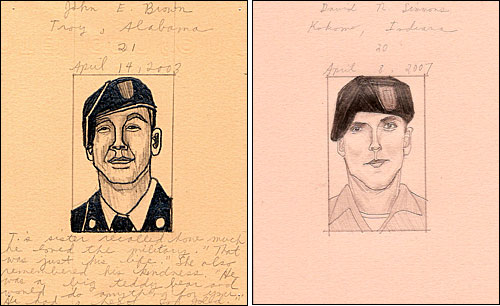

Army Private First Class John E. Brown of Troy, Ala. (left) was killed in Iraq on April 14, 2003, when a grenade exploded inside his Humvee. The writing below his portrait quotes his sister, who remembers John as a "big teddy bear" who "would do anything for you." Private First Class David N. Simmons of Kokomo, Ind. was killed on April 8, 2007 in Baghdad, when his military vehicle was attacked by an improvised bomb and small-arms fire; he had been in Iraq about a week. (Images courtesy of Kent Gallery, NYC) |

A map formed by faces of the fallen

UC

Berkeley artist takes her Iraq War memorial to

Italy's Venice Biennale

BERKELEY – Emily Prince is "probably not the person to ask" about the Venice Biennale. Though it's a leading international showcase for emerging artists — and her inclusion in this year's exhibition is a singular honor — "there are a lot of gaps in my knowledge of that kind of contemporary art," she confesses, and the Biennale is one of those lacunae.

Prince has had other things on her mind this spring. Finishing the semester, for one — she's an Art Practice master's-degree student at UC Berkeley — and drawing portraits (in recent months about 20 per week) for her work-in-progress, "American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan (But Not Including the Wounded, Nor the Iraqis nor the Afghanis)."

Emily Prince (Cathy Cockrell photo) |

The 26-year-old grad student is currently in Venice, installing her memorial work for the Biennale's June 9 opening. It promises to be a challenging task. Since November 2004, Prince has turned out thousands of individual portraits of fallen U.S. troops; for exhibition, each portrait is individually pinned to the gallery wall in a location corresponding to the individual's hometown — forming, in sum, a rough map of the United States.

When creating these portraits in her San Francisco apartment, Prince draws each face in pencil on a wallet-photo-sized piece of paper — these days using the "skinniest, hardest lead I can find" so as to best render the individuality of the person's features. In longhand, she adds biographical details gleaned from an "Honor the Fallen" feature on militarycity.com — typically name, hometown and state, age, date of death, and other information that helps to personalize the portrait, moving it "at least one step away from being a statistic," as she puts it.

When Prince first started the project, she had hundreds of portraits to catch up on. Now, working "almost in real time," she sets aside a day each weekend for rendering portraits of the war's most recent U.S. fatalities. On a separate day, typically, she does detailed planning, using a grid system and a U.S. map (as well as detailed maps of the 50 states) to assign each portrait its location.

The work's resulting shape changes according to the current number of war fatalities and the exhibition space she's assigned. A segment of the project, featuring only the fallen troops from California, was displayed in Los Angeles last fall; the full piece was last shown at a 2005 group exhibition at San Francisco's Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. There the portraits roughly formed the shape of the United States — its precise contours "constantly changing" as additional war deaths were reported and Prince added portraits to the wall.

Prince does not keep a precise count of the number of portraits she's drawn to date; the point of the project, after all, is "not relating to the information as numbers," as she puts it. She does, however, have an "approximate" idea: there will be more than 3,300 at the Venice Biennale's international show.

That exhibition — curated by Robert Storr, dean of the Yale School of Art — is to feature 96 artists, about a fifth of them from the United States. Titled "Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind," its "argument," Storr has said, is that first-rate works combine both concept and beauty.

"American Servicemen and Women…" — though more topical than many of Prince's projects — bears important similarities to the rest of her work: it involves drawing and installation, operates in time, is site-specific, and expresses "a desire to be learning about my environment," as she puts it. So as to help her better understand "the space where I live," much of her art work "ends up being a kind of mapmaking," says Prince.

The UC Berkeley MFA student, a native of the Sierra Nevada foothills, has just completed a set of botanical murals for the Watershed Project, in Richmond, featuring native plants used in habitat-restoration projects (a strong interest for Prince). Following her move to San Francisco last fall from Stanford University, where she double majored in psychology and studio arts, she did a series of drawings cataloguing items in her apartment — from a space heater to kitchen items — "to make a portrait of my home." Her investigations "can be as local as that," she says, or as "global" as a contemplation of the human consequences of war.

Although the Venice Biennale is unknown territory for Prince, she's keenly aware that her memorial installation may engender criticism from the press, the art critics, or the public. With several hundred thousand visitors expected to attend the Biennale over the next seven months, "I fear I'll become the world's village idiot," she says. Will some, for instance, "read" her tribute to America's war dead as one that renders invisible the far heavier Iraqi toll? "I am an American," she reasons. "This is the material I'm allowed to work with."

Eschewing inflated claims about her project, Prince speaks of it as a investigative tool to help her understand and feel more deeply, through its execution, the reality of the "war on terror" in the Middle East. "Hearing the casualties keep climbing made me curious as to who these people were," she's said. "The number was not enough information for me. It was just an abstraction for a situation that deemed elaboration."

To get a better feel for the racial demographics of U.S. fatalities in Iraq, she chose to draw each portrait on one of five different colors of paper — from "honeysuckle" to a medium brown called "bisque" — corresponding to "very basic, general categories of skin tone" of the soldiers. And she deflects the suggestion that she's thinking about the war at every moment of the process. "Spending so much of my time" on the drawings, that would be hard to claim, Prince says. Rather, "it's a visceral experience" through which the human toll of war registers "visually and physically." Sometimes, long after completing a portrait, she'll encounter the person's face again in the news media. When that happens, it can feel hauntingly familiar to Prince — "like somebody I would have seen passing on the street."

"American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan..." was last fully installed at San Francisco's Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in 2005. |