UC Berkeley Press Release

Leonard Nathan, distinguished poet, dies at 82

BERKELEY – Leonard E. Nathan, a professor emeritus of rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley, and a prolific American poet, critic and master of the short lyric, died peacefully on June 3. He was 82.

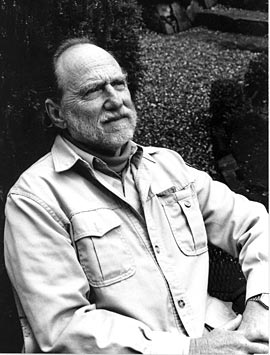

Leonard Nathan (Courtesy Andrew Nathan) |

The author of 17 volumes of poetry, Nathan was a fixture for 50 years in literary circles both on and off the UC Berkeley campus. Ted Kooser, a recent U.S. poet laureate and an English professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, counted Nathan among his mentors, particularly for his "economy of words."

"He was among the finest poets of his generation and will be missed by all of us who practice the art," said Kooser, who struck up a correspondence with Nathan in the 1970s after complimenting Nathan on a poem he had seen in a magazine.

Friends and colleagues said Nathan never won the full national recognition he was due, though that never dampened his exuberance for life and artistic expression.

"I regard him as one of the most under-recognized and undervalued poets of our time. I'm just sorry he died before his quality as a poet was fully recognized," said Thomas Sloane, a fellow professor emeritus of rhetoric at UC Berkeley and a longtime friend.

Nathan's first book of poems, "Western Reaches" (Talisman Press, 1958), brims with images of the California landscape. After a year in India, he published a book about his experiences there titled, "The Likeness: Poems out of India" (Thorpe Springs Press, 1975). That same year, Princeton University Press published Nathan's "Returning Your Call," which was nominated for a National Book Award.

His prose included "Diary of a Left-Handed Bird Watcher" (Graywolf Press, 1996) and "The Poet's Work, an Introduction to Czeslaw Milosz" (Harvard University Press, 1991). He also collaborated on a number of translations, most notably with Milosz on the poems of Anna Swir and Alexander Wat.

As chair of UC Berkeley's then-Department of Speech from 1968 to 1972, Nathan shepherded the department's transformation to Department of Rhetoric. He took very seriously his responsibility as one of the department's founding fathers, colleagues said.

"He was concerned about the welfare of the department," said Michael Mascuch, present chair of the Department of Rhetoric, which he joined just before Nathan retired. "He sought out new colleagues in the department, and was concerned to have them know the special nature of the department. He was looking after a legacy."

That academic legacy, according to Mascuch, is the rhetoric department's enduring "emphasis on the voice ... the way the spoken word resonates in writing, and how we need an ear for that voice. That is something (Nathan) always emphasized in pedagogy."

Nathan was born in El Monte, Los Angeles County, in 1924. His father, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, owned a printing press. Nathan graduated from El Monte Union High School in 1943, and joined the Army's combat engineers in Europe.

After completing his military service, he moved in with an aunt in Los Angeles and attended UCLA on the GI Bill. While taking the bus to college, he met George Hochfield, a fellow World War II veteran and UCLA student, and they became inseparable friends. Both of them transferred to UC Berkeley in 1947.

In Berkeley, the two buddies became roommates and moved into an apartment above a bicycle shop and gallery on College Avenue near Claremont Avenue. Nathan's good humor was contagious, Hochfield said.

"He was a general merrymaker and entertainer. He did card tricks. He told jokes. He flirted outrageously," Hochfield said. "But there was always one thread that ran through his life, and that was poetry. It's literally impossible to separate his life from his poetry. He was totally devoted to it."

Together, Nathan and Hochfield created a journal they called The Formalist, the title representing their objection to "the abandonment of traditional forms by modern poets," according to Hochfield. Nathan's father, Jack, printed the magazine. They sold a few copies on campus before the venture fizzled out.

It was at the friends' College Avenue apartment that Nathan met his wife, Carol, who was a neighbor. They married in 1949 and had one son, Andrew, and two daughters, Julia and Miriam. The family later moved to Kensington.

Andrew Nathan said his father was playful to the end: "He never lost his sense of humor," he said. "I could always get a laugh out of him even as he struggled to do the things we all take for granted. We would discuss odd words such as rutabagas and he would crack up. He always loved to play with language and that was with him to the end."

At UC Berkeley, Nathan earned a bachelor's degree in English in 1950, a master's degree in English in 1952 and a Ph.D. in 1961. He was then hired as a lecturer in UC Berkeley's Department of Speech, and was promoted to associate professor in 1965 and to professor in 1968.

Among other honors, he received the National Institute of Arts and Letters prize for poetry, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Phelan Award for Narrative Poetry, and three silver medals from the Commonwealth Club of California, including one for "The Potato Eaters" (Orchises Press, 1999).

His poems were also published in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, New England Review and The Georgia Review, among other publications. This is how he described his goals as a poet in a vita filed with the Department of Rhetoric:

"Over the years and without self-consciously trying, I have moved closer and closer to the human voice in my verse," he wrote. "But I have also tried to keep a quality - for lack of a better word I call it eloquence - that makes it more than conversation. My hope is to be clear, true and good listening."

Nathan retired from UC Berkeley in 1991. Before his death, he was working with Hochfield on a translation of the poetry of the late Italian poet Umberto Saba. Yale University Press is expected to publish the book some time next year, Hochfield said.

"I would give him a literal translation, and he would work over it, change the order of words, and before long, it was becoming a poem - not any longer the stiff awkward thing that I had given him," said Hochfield, who by then had retired from his post as English professor at State University of New York at Buffalo and moved back to Berkeley.

During this collaboration, Hochfield and Nathan would meet each Friday at The Musical Offering café in Berkeley for lunch, where they would share a tuna fish sandwich and a dessert.

"I will miss those lunches," Hochfield said.

Nathan is survived by his wife of 58 years, Carol Nathan of San Rafael; son, Andrew Nathan of San Anselmo; daughters, Julia Nathan of Harlingen, Texas, and Miriam Mason of Vancouver, Wash.; brother, Marvin Nathan of Berkeley; and four grandchildren.

Plans for a gathering this month to celebrate Nathan's life are pending. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made to the Alzheimer's Association of Northern California and Northern Nevada. For more information on how to donate, visit: http://www.alznorcal.org/.