UC Berkeley Press Release

Geochemist Harold Helgeson has died at 75

BERKELEY – Harold C. Helgeson, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, whose models of geochemical processes deep underground today guide companies exploring for ore, minerals and oil, died on May 28 after a brief battle with lung cancer.

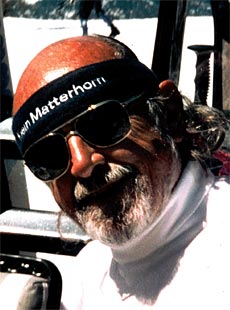

Harold Helgeson (Joachim Hampel/UC Berkeley photo, 1989) |

A resident of San Francisco, Helgeson died at Alta Bates Medical Center in Berkeley at the age of 75.

Helgeson is widely regarded as the founder and preeminent practitioner of theoretical geochemistry. A thorough researcher, demanding teacher and avid sailor, he transitioned from a field geologist prospecting for minerals and gems in Africa to a theoretician modeling the geochemical processes in rocks that create metallic ore deposits and oil.

"These models apply to any underground situation involving water moving through aquifers, like the migration of groundwater, pollutant migration, and at higher temperatures and pressures the reactions of volcanic and metamorphic waters deep in the earth," said Dimitri A. Sverjensky, a professor of geochemistry at The Johns Hopkins University who was a post-doctoral fellow under Helgeson in the 1980s. "He dealt with the origins of all hydrothermal processes, that is, hot water and metallic ore deposits of scarce elements like gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper and molybdenum. He invented the theory to describe the chemistry of water-rock interactions that everybody now uses."

According to William McKenzie, a retired consulting geochemist and Helgeson's long-time friend and collaborator, Helgeson's data and theoretical models are used by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory scientists to predict the transport of radionuclides under Nevada's Yucca Mountain, the proposed repository of the nation's radioactive waste.

Known for his detailed - and long - theoretical papers, this past year Helgeson completed a 300-page paper summarizing 17 years of research that turns the reigning theory of how oil is generated underground on its head. According to Sverjensky, Helgeson and his coauthors argue that the oil extracted today from wells is just the first pressing of more extensive deposits deeper underground. This theory predicts large, untapped oil reserves in the Earth, which may be difficult to extract.

"It is a revolutionary idea about the origin of petroleum, very extensively documented with incredibly detailed calculations backing it up, so, right or wrong, it will stand as a phenomenal effort," Sverjensky said.

Coauthored by McKenzie; Denis L. Norton, formerly of the University of Arizona; Laurent Richard of the University of Nancy, France; and UC Berkeley geologist Alexandra M. Schmitt; the paper is to be printed in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta later this year.

According to Sverjensky, Helgeson was larger than life. He traveled and lectured extensively, his lectures known for their complex diagrams, clarity and the sheer force of their delivery. He enjoyed socializing and discussing science into the early morning hours, Sverjensky said, adding, "Few hosts could keep up with his schedule, but they never forgot the experience."

"He'd take people sailing on his boat in the bay and be gone for two days," McKenzie said. "When he returned, they'd all be wiped out, but Helgeson would show up in his class and teach his lecture."

Helgeson enjoying one of his favorite sports, skiing. (France Damon Helgeson, 1994) |

"He was the quintessential bon vivant who loved to ski and sail, listen to Jimmy Buffett and cheer the Giants from his season seats. He loved to spend many, many hours in lively scientific or social discourse at long, long lunches," said his wife, France Damon Helgeson. "'The purpose of life,' he would always say, 'was to have lunch!'"

"The mark he has left on geochemistry is profound, ranging from significant theoretical advances, to his many excellent students, to the oft-told Helgeson stories," wrote Susan L. Brantley, president of the Geochemical Society.

Helgeson was born on Nov. 13, 1931, in Minneapolis, Minn., and grew up in St. Paul. After completing his B.S. in geology at Michigan State University in 1953, he worked for a year as an exploration geologist for Technical Mine Consultants in Canada, prospecting for uranium, then served for two years in the Korean War as a photo-radar intelligence officer in the U.S. Air Force and was based in Wiesbaden, Germany.

After his military service, he spent four years as a mining and exploration geologist for Anglo-American Corp. in South Africa, first in diamond exploration for the De Beers company's subsidiary in what is now Namibia, and then as an underground mining geologist at the President Steyn Gold Mine in Welkom, and the Nkana Copper Mine in Kitwe, Zambia. According to Sverjensky, it was while very deep underground in one of these mines that Helgeson suddenly realized he might find a different career appealing.

He returned to the United States in 1959 and entered Harvard University as a graduate student, studying under Robert M. Garrels, a pioneer in low-temperature geochemistry who became a close friend. Helgeson received his Ph.D. in 1962, and his thesis, published as a book in 1964, laid out the foundations of the field of theoretical high-temperature geochemistry.

After a stint as a research chemist for Shell Development Co. in Houston, Texas, where he investigated geothermal fields, Helgeson in 1965 joined Garrels at Northwestern University, where he began his academic career as an assistant professor. Over the next five years, he, Garrels and Fred T. Mackenzie published a series of definitive papers on the theory of water-rock interactions at low and high temperatures and pressures, and Helgeson published a paper providing the first internally consistent thermodynamic data needed to apply that theory.

One of Helgeson's great achievements, McKenzie said, was conceiving and then constructing a predictive model of water-rock interactions over the huge range of temperatures and pressures inside the earth.

"He realized that he didn't have enough data for all the minerals and aqueous species, and that it would take a thousand chemists a thousand years, at least, to do all the experiments to measure those properties," he said. "So what he did was calculate them."

By doing this, he demonstrated the value of theoretical calculations that could be used as tools, along with the more traditional field and laboratory investigations, to gain insight into geochemical processes.

Helgeson joined the UC Berkeley faculty in 1970, expanding his work into a comprehensive, predictive approach for inorganic and organic species and biomolecules that was scrupulously documented in papers between 1974 and 2007. In recent years, he became interested in the interaction of life with physical processes underground, helping to create the emerging field of biogeochemistry, and applying his knowledge of theoretical chemistry to biological problems, including protein folding, metabolic activity in hydrothermal systems, and the origin of life.

"Although many found these papers intimidating, those who made the effort to read them found them to be models of clarity and scholarship," Sverjensky said. "Helgeson always maintained that he was writing for posterity."

He pioneered the application of computers to the modeling of geochemical processes using the results of his calculations. The computer codes produced in his theoretical geochemistry laboratory, known as "Prediction Central," are now used by geoscientists and engineers around the world.

"Working with Helgeson on a daily basis, one marveled at the tenacity of his efforts to reconcile experimental and observational data with theory, and found one's own assumptions constantly challenged by his pervasive drive to see beyond how nature appears to be organized to a deeper, sometimes counterintuitive, fundamental meaning," said Everett L. Shock, professor of geochemistry at Arizona State University and a former student of Helgeson's.

Helgeson served as a director of the Geochemical Society from 1973 to 1976. He received the Goldschmidt Medal from the Geochemical Society in 1998 and the Urey Medal from the European Association of Geochemistry in 2004.

Helgeson is survived by his wife, France Damon Helgeson of Santa Cruz, Calif., and three children: Christopher Helgeson of Mountain View, Calif.; Kimberly Helgeson of Hollywood, Calif.; and Broghan Helgeson of Santa Cruz, a student at Tufts University.

A departmental and family memorial is planned for the fall.