UC Berkeley Press Release

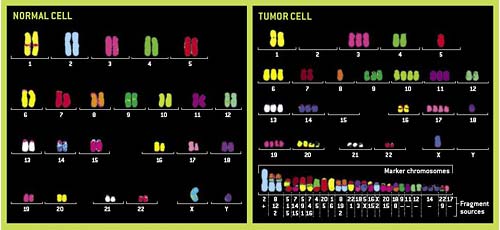

The chromosomal fingerprint, or karyotype, of a normal human cell (left), includes 46 paired chromosomes. The distinctive karyotype of an aneuploid breast cancer cell, however, (right) includes duplicates of entire chromosomes, missing chromosomes, and chromosome stubs. The chromosome pattern also includes marker chromosomes seen in all the cancer's cells, indicating changes that originated in the cell that gave rise to the cancer. Numbers under each marker chromosome indicate the chromosome from which the fragment came; while plus and minus signs identify those that are larger or smaller than usual. (Peter Duesberg/UC Berkeley) |

Drug resistance argues against mutation theory of cancer

BERKELEY – Thirty-six years into the war on cancer, scientists have not only failed to come up with a cure, but most of the newer drugs suffer from the same problems as those available in the pre-war days: serious toxicity, limited effectiveness and eventual resistance.

This is no surprise to University of California, Berkeley, genetics researcher Peter Duesberg, professor of molecular and cell biology. According to his novel yet controversial "chromosomal" theory of cancer, which is receiving increased attention among cancer researchers, each cancer is unique, and there is no magic bullet.

"The mutation theory of cancer says that a limited number of genes causes cancer, so cancers should all be more or less the same," Duesberg said. The chromosomal theory, which he laid out in an article in the May 2007 issue of Scientific American, implies instead that, "even if cancers are from the same tissue, and are generated with the same carcinogen, they are never the same. There is always a cytogenetic and a biochemical individuality in every cancer."

The most that can be expected from a drug, he said, is that it is less toxic to normal cells than cancer cells, and that as a result a cancer detected early can be knocked back by chemotherapy. His chromosomal theory offers hope of early detection, however, since it ascribes cancer to chromosomal disruption, called aneuploidy, that can be seen easily through a microscope.

"By screening for aneuploidy, you could detect the cancer early and also see what possible drugs to use and whether drugs would even help," Duesberg noted. "Then, you wouldn't have to give a cocktail of drugs that includes all the best poisons, but you could leave out those you could tell wouldn't work. If you could cut chemotherapy drug toxicity in half or two-thirds, and direct it better at cancer, that is some progress. But it is not a cure."

Duesberg and colleagues discuss the major problem of drug resistance in cancer and how it supports the chromosomal theory of cancer in a paper appearing in the current issue of the journal Drug Resistance Updates (Vol. 10, issue 2).

Duesberg proposed in 2000 that the assumption underlying most cancer research today is wrong. That assumption, that cancer results from a handful of genetic mutations that drive a cell into uncontrolled growth, has failed to explain many aspects of cancer, he said, and has led researchers down the wrong path.

His alternative theory is that cancer results from aneuploidy - that is, duplication or sometimes loss of one or more of our 46 chromosomes, which throws thousands of genes out of whack. This condition, generated by a defect in the mechanism that duplicates chromosomes during cell growth, leads to more and more chromosomal disorder as the cells divide and proliferate, disrupting even more genes and providing ample opportunity for the development of resistance to drugs being used to control the cancer.

"In this new study and in one published in 2005, we have proved that only chromosomal rearrangements, rather than mutations, can explain the high rates and wide ranges of drug resistance in cancer cells," he said.

Duesberg even argues that the anti-leukemia drug imatinib (GleevecŪ), the poster child for rational drug design once hailed as a therapy that would make drug resistance a thing of the past, has been rendered less useful because the aneuploid nature of leukemia has led to resistance. In fact, he said, this resistance suggests that imatinib is not a highly targeted drug, as advertised, but just another cell "poison" that happens to kill more leukemia cells than normal cells.

Development of drug resistance in cancer is one of the strongest arguments for the aneuploidy, or chromosomal, theory of cancer, Duesberg said, and is one aspect of cancer that can be studied experimentally. Normal cancers typically take decades to develop, making it hard to link cause and effect and to prove or disprove either the mutation or chromosomal theories. Drug resistance, however, often occurs quickly. Many cancer patients are initially heartened when their cancer starts to respond to a drug, only to find the cancer suddenly stop responding and begin to grow again.

In a paper responding to Duesberg's in the same issue of Drug Resistance Updates, Tito Fojo of the National Cancer Institute argues that there are many ways in which the mutation theory of cancer can explain drug resistance. A gene mutation, deletion, translocation or amplification could disrupt many cell functions, leading to resistance, or could inactivate or damage the doors through which a drug enters a cell.

Duesberg counters that aneuploidy is simpler and can explain the common development of resistance to many unrelated drugs within the same cancer. He has shown in experiments that aneuploidy causes many gene disruptions such as breakage or translocation each time a cancer cell divides, providing an opportunity for it to develop resistance to many drugs. Gene mutation rates in cancer cells, however, are no different from mutation rates in normal cells, making it difficult to understand how several simultaneous mutations can occur in cancer to make them resistant to more than one drug.

"The fundamental problem these conventional theories don't address is why it (drug resistance) doesn't happen in normal cells," he said. "Why aren't we all getting resistant to any toxic drug we are exposed to? Why does it happen only in cancer cells? Why do cancer cells become resistant and the patients don't?"

In his experiments, Duesberg and his colleagues focus on the chromosomal fingerprint of a cell, its karyotype. For decades, physicians have known that cells of a particular cancer have the same set of marker chromosomes, a rogues gallery of normal chromosomes and stumps of chromosomes. Duesberg and UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Ruhong Li showed that the karyotype of drug-resistant cancer cells differs significantly from the karyotype of drug-sensitive cells from which they grew.

Clinicians have found, for example, that the gene expression profile of a breast cancer cell can tell them which treatments work best. This indicates, Duesberg said, that chromosomal disruption, which affects the expression of thousands of genes, is a better explanation for the cause of breast cancer than is the mutation theory.

"They see now, more and more, that aneuploidy cannot be ignored. It is a big elephant compared to their little mutations," he said.

Also, the more often a cancer changes karyotypes as it grows, he said, the more drugs it becomes resistant to.

"The inherent instability of aneuploidy thus explains the enormous adaptability of cancers against cytotoxic drugs and dims hopes for gene-specific therapies," Duesberg, Li and their co-authors wrote.

While this is bad news for cancer patients, Duesberg pointed out that the aneuploidy theory of cancer also provides a means for earlier detection of cancer. He and colleague David Rasnick have developed a cell scanner to search for aneuploid cells, such as from a Pap smear for cervical cancer or from biopsies for breast cancer. Rasnick formed a company to market the device, which recently was acquired by Modern Technology Corp. Aneuploid scanning is already employed in some European countries to screen for cancer.

Coauthors with Duesberg and Li on the new paper are Ruediger Hehlmann and Alice Fabarius of the Medical Clinic at the University of Heidelberg at Mannheim, Germany; Rainer Sachs, a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of mathematics and physics; and Madhvi B. Upender of the Center for Cancer Research of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

The work was supported by the Foundation for Advancement in Cancer Therapy, the Abraham J. and Phyllis Katz Foundation, philanthropists Herbert Bernheim and Robert Leppo, and other private sources.