UC Berkeley Press Release

New biochip could replace animal testing

BERKELEY – With the cosmetics industry facing a European ban on animal testing in 2009, a newly developed biochip could provide the rapid analysis needed to insure that the chemicals in cosmetics are nontoxic to humans.

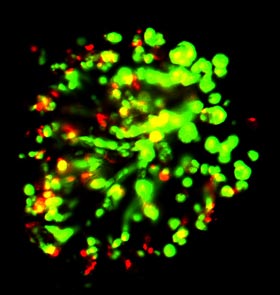

Close up of a DataChip spot. Human cells (green live, red dead) are encapsulated in an algae extract and treated with chemicals or liver metabolites of chemicals to assess toxicity. (Moo-Yeal Lee/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute ) |

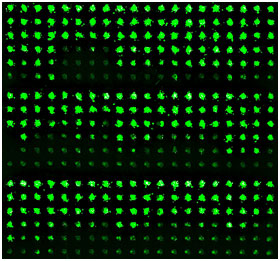

The biochip, announced this week in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is a suspension of more than a thousand human cell cultures in a three-dimensional gel on a standard microscope slide. Each cell culture is capable of assessing the toxicity of a different chemical. According to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Solidus Biosciences, Inc. of Troy, N.Y., cultures of skin cells in this so-called DataChip could be used to rapidly screen new chemicals for skin toxicity or irritability.

By adding other types of cells, such as lung or heart cells, and combining the DataChip with another biochip - the MetaChip - that the researchers created several years ago, cosmetics or chemical companies could also test whether chemicals are toxic to other organs, not just skin.

"The DataChip expands the capabilities of the MetaChip and enables it to test for toxic effects of chemicals and their metabolites throughout the body," said co-lead author Douglas S. Clark, UC Berkeley professor of chemical engineering and co-founder of Solidus Biosciences, the company that is working to commercialize the chips. "It is one step closer to a replacement for animals in evaluating product safety, as well as to a personalized system that can predict the toxicity of drugs in individual patients."

The MetaChip that was reported two years ago contains liver enzymes immobilized on a microscope slide. Liver enzymes can sometimes alter seemingly safe chemicals and make them toxic. The MetaChip mimics this process, quickly metabolizing a chemical to produce compounds the liver itself would produce. The DataChip provides an equally fast way to determine the effect of these metabolites on cells.

For drug companies, the combination of the MetaChip and the DataChip offers a rapid way to predict whether a drug candidate or its metabolite is toxic. The chips will also enable chemical companies to comply with new legislation stipulating that chemicals undergo toxicity analysis.

"We looked at the issues facing companies and realized that we needed to develop something that was low-cost, high-throughput, easily automatable and did not involve animals" said co-lead author and Solidus Biosciences co-founder Jonathan S. Dordick, the Howard P. Isermann '42 Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Rensselaer. "We developed the MetaChip and DataChip to deal with the two most important issues that need to be assessed when examining the toxicity of a compound - the effect on different cells in our body and how toxicity is altered when the compound is metabolized in our bodies."

The collaborative team sees the combined chips as an efficient, more accurate way to test drug compounds for toxicity earlier in the discovery process, before a lot of money has been invested in a drug candidate. However, according to Clark, pharmaceutical companies are only one potential user, and not necessarily the first.

"Obviously cosmetics need to be safe, and ensuring the safety of new compounds without testing them on animals presents a new challenge to the industry, especially as the number of compounds increases," said Clark. "These chips can meet this challenge by providing comprehensive toxicity data very quickly and cheaply."

Within the next 5 to 10 years, assuming the cost of sequencing all of a person's genes becomes generally affordable, people will be able to mine their personal genomes for information on the types and levels of liver enzymes that determine how they react to specific drugs and then reproduce this profile on a MetaChip to prescreen all drugs before they're administered to determine safe and effective doses.

Human liver cells are dotted across the new DataChip to quickly determine if various chemicals, drugs, and drug candidates are toxic. When coupled with the MetaChip, the two biochips could provide a highly predictive alternative to animal testing. (Moo-Yeal Lee/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute) |

"We have the fundamental platform and concept, and there is the potential to expand considerably beyond that to test for many different biological responses, such as allergic responses or binding of a chemical to a receptor to trigger a reaction," Clark said. "For personalized medicine, that is exactly what you'd want to do."

Dordick and Clark were joined in the research by Moo-Yeal Lee and Michael G. Hogg of Solidus Biosciences; R. Anand Kumar of UC Berkeley; and Sumitra M. Sukumaran of Rensselaer.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the New York State Office of Science and Technology (NYSTAR).