UC Berkeley Press Release

Rich nations' environmental footprint falls on poor

BERKELEY – The environmental damage caused by rich nations disproportionately impacts poor nations and costs them more than their combined foreign debt, according to a first-ever global accounting of the dollar costs of countries' ecological footprints.

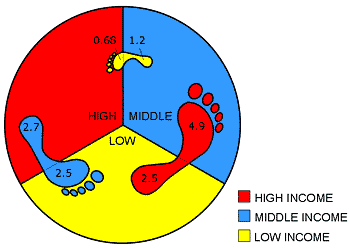

Upper bound footprints of income groups on other groups

(trillions 2005 international $)

"At least to some extent, the rich nations have developed at the expense of the poor and, in effect, there is a debt to the poor," said coauthor Richard B. Norgaard, an ecological economist and UC Berkeley professor of energy and resources. "That, perhaps, is one reason that they are poor. You don't see it until you do the kind of accounting that we do here."

The calculation of the ecological footprints of the world's low-, middle- and high-income nations drew upon more than a decade of assessments by environmental economists who have tried to attach monetary figures to environmental damage, plus data from the recent United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and World Bank reports.

Because of the monumental nature of such an accounting, the UC Berkeley researchers limited their study to six areas of human activity. Impacts of activities that are difficult to assess, such as loss of habitat and biodiversity and the effects of industrial pollution, were ignored. Because of this, the researchers said that the estimated financial costs in the report are a minimum.

"We think the measured impact is conservative. And given that it's conservative, the numbers are very striking," said Srinivasan, who is now at the Pacific Ecoinformatics and Computational Ecology (PEaCE) Lab in Berkeley. "To our knowledge, our study is the first to really examine where nations' ecological footprints are falling, and it is an interesting contrast to the wealth of nations."

Srinivasan, Norgaard and their colleagues reported their results this week in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"In the past half century, humanity has transformed our natural environment at an unprecedented speed and scale," Srinivasan said, noting that the Earth's population doubled in the past 50 years to 6.5 billion as the average per-capita gross world product also doubled. "What we don't know is which nations around the world are really driving the ecological damages and which are paying the price."

Norgaard said that the largest environmental impact by far is from climate change, which has been assessed in previous studies. The current study broadens the assessment to include other significant human activities with environmental costs and thus provides a context for the earlier studies.

The study makes clear, for example, that while deforestation and agricultural intensification primarily impact the host country, the impacts from climate change and ozone depletion are spread widely over all nations.

"Low-income countries will bear significant burdens from climate change and ozone depletion. But these environmental problems have been overwhelmingly driven by emission of greenhouse gases and ozone-depleting chemicals by the rest of the world," Srinivasan said.

Climate change is expected to increase the severity of storms and extreme weather, including prolonged droughts and flooding, with an increase in infectious diseases. Ozone depletion mostly impacts health, with increases expected in cancer rates, cataracts and blindness All of these will affect vulnerable low-income countries disproportionately.

In addition to climate change and ozone depletion, overfishing and conversion of mangrove swamps to shrimp farming are areas in which rich nations burden poor countries.

"Seafood derived from depleted fish stocks in low-income country waters ultimately ends up on the plates of consumers in middle-income and rich countries," Srinivasan said. "The situation is similar for farmed shrimp. For such a small, rare habitat, mangroves, when cut down, exact a surprisingly large cost borne primarily by the poor- and middle-income countries."

The primary cost is loss of storm protection, which some say was a major factor in the huge loss of life from 2005's tsunami in Southeast Asia.

Deforestation, on the other hand, can exacerbate flooding and soil erosion, affect the water cycle and offshore fisheries and lead to the loss of recreation and of non-timber products such as latex and food sources. Agricultural intensification can lead to drinking water contamination by pesticides and fertilizers, pollution of streams, salinization of croplands and biodiversity loss, among other impacts.

When all these impacts are added up, the portion of the footprint of high-income nations that is falling on the low-income countries is greater than the financial debt recognized for low income countries, which has a net present value of 1.8 trillion in 2005 international dollars, Srinivasan said. (International dollars are U.S. dollars adjusted to account for the different purchasing power of different currencies.) "The ecological debt could more than offset the financial debt of low-income nations," she said.

Interestingly, middle-income nations may have an impact on poor nations that is equivalent to the impact of rich nations, the study shows. While poor nations impact other income tiers also, their effect on rich nations is less than a third of the impact that the rich have on the poor.

Norgaard admits that "there will be a lot of controversy about whether you can even do this kind of study and whether we did it right. A lot of that will just be trying to blindside the study, to not think about it. What we really want to do is challenge people to think about it. And if anything, if you don't believe it, do it yourself and do it better."

Srinivasan led the three-year study in collaboration with Norgaard, who provided economic expertise; John Harte, professor of energy and resources at UC Berkeley, who initiated the idea and the basic framework for the study; post-doctoral fellow Susan Carey of the UC Berkeley Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management; Reg Watson, a senior research fellow at the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia; UC Berkeley Energy and Resources Group graduate students Adam B Smith, Amber C. Kerr, Laura E. Koteen and Eric Hallstein; and former UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow Paul A. T. Higgins, who is now at the American Meteorological Society in Washington, D.C.