UC Berkeley Press Release

Genome of marine organism tells of animals' one-celled ancestors

BERKELEY – The newly sequenced genome of a one-celled, planktonic marine organism, reported today (Thursday, Feb. 14) in the journal Nature, is already telling scientists about the evolutionary changes that accompanied the jump from one-celled life forms to multicellular animals like ourselves.

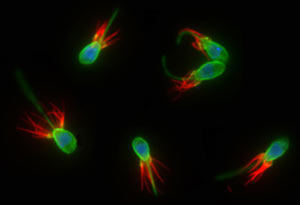

Choanoflagellates are aquatic microbes distinguished by a flagellum (green) used for swimming and feeding, surrounded by a collar of tentacles (red) against which bacterial prey are trapped. The nucleus of the one-celled organism is highlighted in blue. (Nicole King lab/UC Berkeley) |

The sequencing and analysis was performed by the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (JGI) in Walnut Creek, Calif., in collaboration with researchers from UC Berkeley and eight other institutions.

According to King, biologists know almost nothing about these organisms, aside from the fact that they are an important food for krill, which are the main source of food for baleen whales, and that, by consuming large quantities of bacteria, choanoflagellates play a major role in the carbon cycle of the oceans. Yet, because choanoflagellates and animals shared a common ancestor between 600 million and a billion years ago, they hold a key to understanding the origins and evolution of animals.

"Choanoflagellates are the closest living unicellular relatives of animals and, as such, can help us learn about our history and the history of life on Earth, which has been dominated by one-celled organisms," said King, an assistant professor of integrative biology and of molecular and cell biology, and a 2005 MacArthur "genius" Award winner. "They help shed light on the biology and genome content of the unicellular organisms from which we evolved."

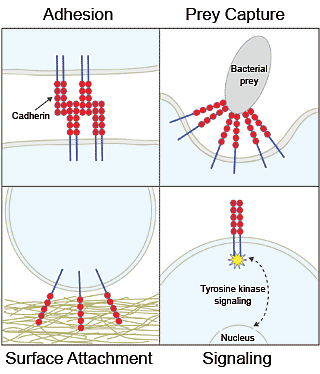

Cadherin proteins were discovered in animals, where they mediate cell-cell adhesion and signaling. Researchers have since found them in one-celled choanoflagellates, where their role is unknown. Choanoflagellates cadherins may play analogous roles, however, ranging from the capture of bacterial prey (a form of cell adhesion) or attachment to surfaces in the environment, to the detection of environmental cues that trigger cellular responses (cell signaling). (Nicole King lab/UC Berkeley) |

"In animals, some of these proteins, called cadherins, evolved for linking cells together; they are the glue that prevents clumps of cells from falling apart," King said. "Choanoflagellates show no hint of multicellularity, but they have 23 genes for cadherin proteins, about the same as the fruit fly or the mouse."

In the Science paper, King and graduate student Monika Abedin report that some of these proteins are found around the base of the choanoflagellate cell, where the choanoflagellate attaches to surfaces, and around the tentacles, where bacteria are captured and ingested.

Perhaps, they argue, the last single-celled ancestor of all animals (including humans) employed these ancient cadherin proteins to bind and eat bacteria, while more complex metazoans adopted these proteins for gluing cells into a larger, many-celled creature. "The transition to multicellularity likely rested upon the co-option of diverse transmembrane and secreted proteins to new functions in intercellular signaling and adhesion," they wrote in Science.

"Choanoflagellates really are a unique window back in time to the origin of animals and humans. They are our best way of triangulating on that last unicellular ancestor of animals, because the fossil record is not there," said Dan Rokhsar, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and program head for computational genomics at JGI. King and Rokhsar also are members of UC Berkeley's Center for Integrative Genomics.

Choanoflagellates are found abundantly in salt and fresh water around the world, where they gorge on bacteria. At about 10 microns across, they're about the size of another one-celled eukaryote, yeast. While yeast are well known to genetics researchers, however, choanoflagellates are not - a situation King hopes will change now that the genome is sequenced.

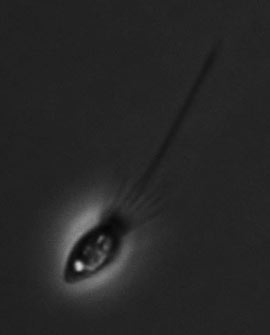

Microscope image of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis, magnified 1000 times, showing its long central flagellum and collar of tentacles. (Mark Dayel/UC Berkeley) |

King and Rokhsar successfully proposed the choanoflagellate for sequencing several years ago as part of the Department of Energy's Microbial Genome Program, and in the intervening years, King worked on isolating enough uncontaminated DNA for sequencing. The draft genome, completed and annotated in 2007, consists of about 9,200 genes. It is similar in size to the genomes of fungi and diatoms, but much smaller than the genomes of metazoans. Humans, for example, have about 25,000 genes.

Interestingly, the choanoflagellate has nearly as many introns - non-coding regions once referred to as "junk" DNA - in its genes as humans do in their genes, and often in the same spots. Introns have to be snipped out before a gene can be used as a blueprint for a protein and have been associated mostly with higher organisms.

The choanoflagellate genome, like the genomes of many seemingly simple organisms sequenced in recent years, shows a surprising degree of complexity, King said. Many genes involved in the central nervous system of higher organisms, for example, have been found in simple organisms that lack a centralized nervous system.

Likewise, choanoflagellates have five immunoglobulin domains, though they have no immune system; collagen, integrin and cadherin domains, though they have no skeleton or matrix binding cells together; and proteins called tyrosine kinases that are a key part of signaling between cells, even though Monosiga is not known to communicate, or at least does not form colonies.

These findings are helping King and her colleagues assemble a picture of what the original common ancestor of humans and choanoflagellates looked like and also get hints about the first animals.

"It remarkable to what extent we can figure out how those animal ancestors must have been able to stick together and communicate with each other, at least in ways that allow you to make hypotheses about what those first steps toward animals looked like," Rokhsar said.

Nevertheless, it is not always easy determining which genes were in the last common ancestor of choanoflagellates and humans, and which are new. Choanoflagellates and humans have been evolving for the same length of time, so differences between the genomes may reflect genes that have been lost by choanoflagellates as much as genes gained by humans. Comparison of the Monosiga genome to that of other organisms, including another choanoflagellate - a colony-former called Proterospongia, whose genome is due to be sequenced by the National Institutes of Health - may answer such questions.

King has hopes that the Monosiga genome will answer many questions of animal evolution and illuminate the biology of this poorly understood aquatic creature.

"This is a new era, where we start with a genome to understand the biology of an organism," King said, noting a similar situation with the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis, sequenced in 2007. "The genome is the toehold."

Other authors of the Nature paper are M. Jody Westbrook, Susan L. Young, Monika Abedin, Jarrod Chapman, Stephen Fairclough, Yoh Isogai, Nicholas Putnam, Kevin J. Wright, Richard Zuzow, William Dirks, David Goodstein, Jessica Lyons, Scott Nichols and Daniel J. Richter of UC Berkeley's Department of Molecular and Cell Biology and the campus's Center for Integrative Genomics; Robert Tjian and Daniel Rokhsar, UC Berkeley professors of molecular and cell biology; Alan Kuo, Uffe Hellsten, Asaf Salamov, Harris Shapiro and Igor V. Grigoriev of JGI, along with the JGI sequencing team; Ivica Letunic and Peer Bork of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany; Michael Marr of Brandeis University; David Pincus, Matthew Good and Wendell A. Lim of UC San Francisco; Antonis Rokas of Vanderbilt University; Derek Lemons and William McGinnis of UC San Diego; Wanqing Li and W. Todd Miller of Stony Brook University in New York; Andrea Morris of the University of Michigan; and Gerard Manning of the Razavi Newman Bioinformatics Center at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif.