UC Berkeley Press Release

Breath of Life for California's native languages

BERKELEY – At a time when only about half of California's 90-plus indigenous languages have living speakers, a language conference being held this month at the University of California, Berkeley, may help tribal members become the first people to speak their endangered tribal languages in 50 years.

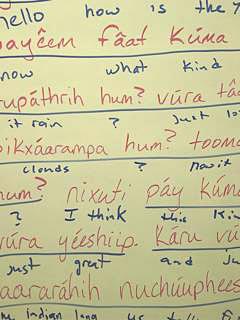

Karuk vocabulary (above) is part of the Indian education curriculum in the Trinity-Shasta Joint Unified School District. (Courtesy of the Trinity-Shasta Joint Unified School District) |

Leanne Hinton, UC Berkeley professor emeritus of linguistics, co-founder of the June 8-14 "Breath of Life" conference and author of the "How to Keep Your Language Alive" (2002) handbook, said that a key goal of the conference is to prepare participants to take their languages home and to help turn learning native languages - as a very first language - into a fundamental feature of Indian childhood.

"The school is great for language learning, but if a community really wants its language to be alive, it has to be using it at home," Hinton said. "The tribes are making progress, and there are people who are teaching it to kids at home."

Home instruction helps children to bond emotionally with their language, according to Hinton, whereas classroom learning reflects a more intellectual and dry approach.

To learn their native languages, a record 70 participants representing more than 30 different California Indian languages are signed up for the biennial conference, which began 14 years ago. Close to 500 people have attended one or more of the campus workshops. The conference is being sponsored by UC Berkeley's linguistics department and its Survey of California and Other Indian Languages research center and archive, in partnership with the non-profit group Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival.

Supahan said she spoke recently with a tribal member who said "he kept thinking that someone would be there and would somehow - miraculously - teach him and others the language, but he's now realized that he has to step up and do it himself."

Two Paiute girls, daughters of a 2004 "Breath of Life" participant, take a break to explore the computers in the Martin Luther King Jr. Student Union. Technology is considered to have played a role in assisting language revitalization efforts, particularly for tech-savvy youths. (Courtesy of Breath of Life) |

California Indians benefit from a lot of exposure to what's happening with native languages in the state, according to Richardson. "We see different stages of loss and reclaiming (languages)," she said. "We all get that we're all fighting for the same thing."

To learn their languages, conference participants will work with mentors, including UC Berkeley linguistics faculty members and students, and utilize the rich materials in the campus archives. They will learn elementary vocabulary and useful phases as well as discover phonetic tools to aid in deciphering written records and audio recordings of their languages, and they will develop word lists and begin dictionaries.

They will explore UC Berkeley's extensive linguistic resources, including field notes, journals, and recordings on tape and wax cylinders. Their schedule includes field trips to the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages; the Hearst Museum of Anthropology and its comprehensive Native California collection; an archival information site at Doe Library; and the campus's Berkeley Language Center, which supports the learning and teaching of heritage and foreign languages.

The Berkeley Language Center has recordings in about 90 indigenous languages - most endangered or rare - and almost all of the audio tapes of music and language are available to the public online. Listeners can discover language treasures such as Klamath words for nature, foodstuffs and culture; stories, songs and conversations in Chumash; a Southern Sierra Miwok song and a story about chasing wild horses; and Central Pomo words and phrases for acorn mush preparation. Similarly rich holdings can be found in all the campus archives that the conference participants will visit.

"People at the conference learn how to find their way around the archives and how to search for what they need," said Hinton.

Richardson, who is majoring in anthropology and studio art and minoring in linguistics at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, has used the UC Berkeley archives during two previous Breath of Life conferences to gain new grammatical knowledge of Karuk that she said helps her to use written materials to teach others. She also collected Karuk songs to bring home, learned information that helped her devise a curriculum for basket weaving classes to be taught in Karuk, and recorded a CD of a special "gathering song" for women that she shared with basket weaving teachers in her area.

With fewer and fewer California Indian languages that have even a handful of native speakers left, the campus's language documentation and related resources take on an even larger role in today's language revitalization efforts.

The conference finale on Saturday, June 14, will feature "final projects" that can be anything from songs, conversations, prayers or stories in the participants' tribal languages. In recent years, participants from the Mutsun tribe served up a translation of Dr. Seuss's "Green Eggs and Ham."

But the end of the conference will mark a beginning as participants return with newfound knowledge to their communities, schools and homes, Hinton said.

With the help of a stipend received as part of the 2006 Lannan Foundation's Cultural Freedom Award, Hinton will continue working after the conference with Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival on a how-to language instruction manual for Indian families in California and across the country to use at home.

It is the season for summer camps, and such activities outside the home can provide critical support for language instruction, Hinton said. "If you don't have community support and social capital (for the endangered language) outside the family, the child is likely to reject the language," she added.

As for learning Indian languages in school, Hinton and others said that mandates for and a focus on standardized testing in English under the federal "No Child Left Behind" Act threaten to undermine indigenous language instruction.

California's teacher credential requirements also can hinder the hiring of native language teachers, although some tribes are fighting for alternative, tribal assessment and certification of native language teachers. The state's approach would take current teachers out of the classroom for years in order for them to pursue academic requirements, said Supahan.

The few current teachers are already trained in their native language and in methodology for teaching languages, she said. "We can't afford to force people to leave (for more training)," said Supahan. "When they come back, those few fluent elders who remain and who continue to be their mentors will likely no longer be here."

Tribal support for language instruction varies, and although indigenous language immersion schools operate outside the state, there are no such schools in California yet. Some tribal leaders focus more on immediate economic needs than on language revitalization, Hinton said, and some tribes are so small and scattered that it's impractical for them to run their own language schools, even if they had enough speakers to handle the teaching load.

Some Indian parents or grandparents who spoke their native languages opted in years past not to share it with their children, Hinton said, because they thought that growing up with English as their primary language would ease the children's way in the world.

That outlook appears to be changing.

In a 2005 report, students at Hoopa High School in Hoopa, Calif., talked about why they were taking courses to learn native languages. "With the languages come values and ways to view the world that are unique to the language," said one unidentified youth. "If those values and views are forgotten and no longer learned, where would that put us as a people who have changed so much so fast already? Could we continue our dances without prayers in the languages? Would we value our valleys, our rivers and our fish in the same way?"

"Language revitalization is always an uphill battle, but people are getting increasingly excited about it," Hinton said.

"Those kids are now thinking about what they lost, and a generation that didn't get to learn their languages is fighting to get them back so they can give them to their kids," she said.

This map reflects California’s different Indian languages and the regions they represent. |