UC Berkeley Press Release

Michael Baxandall, noted art historian, dies at 74

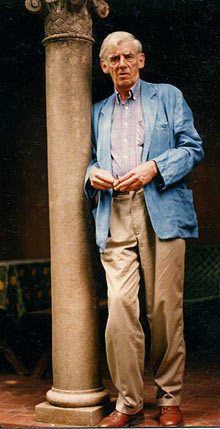

BERKELEY – Michael Baxandall, an acclaimed art historian, author and professor emeritus of art history at the University of California, Berkeley, died in London on Aug. 12. He was 74.

Michael Baxandal (Svetlana Alpers photo) |

He taught at UC Berkeley from 1986 until his retirement in 1996, a decade that colleagues said coincided with the Department of Art History's emergence as one of the most highly regarded in the nation.

Baxandall was born Aug. 18, 1933, in Cardiff, Wales. His father was director of the National Museum of Wales, a curator at the Manchester Art Gallery and director of the Scottish National Gallery. His paternal grandfather served as curator at the Science Museum in London.

He earned a bachelor's degree from Cambridge University in 1954, and then attended the University of Pavia in Italy and University of Munich in Germany. He also was a junior research fellow at the Warburg Institute at the University of London, where he worked with the Warburg's acclaimed art historian Ernst Gombrich. Later, he worked to catalogue German sculpture at London's Victoria and Albert Museum.

Baxandall did not complete his doctoral dissertation, but published his research in his first book, "Giotto and the Orators" (1971), which dealt with the relationship between rhetoric and visual art in the 14th and 15th centuries.

In another book, "Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy" (1972), Baxandall introduced the concept of the "Period Eye," which became influential beyond the study of art history. He showed that both painters and their mercantile and aristocratic patrons shared visual skills that were not specific to looking at pictures, but were valued in the larger society. How this cognitive style related to pictorial style formed the core of this little, but highly acclaimed, book.

In "The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany" (1980), which won the Mitchell Prize in Art History, Baxandall expanded on "Painting and Experience" to assess the lives and practices of artists and merchants in Central Europe and how the works of art they created and patronized served as what he called "lenses bearing on their own circumstances."

In the book "Patterns of Intention" (1985), Baxandall focused on factors that shaped the mental lives of various artists. The material was first delivered by Baxandall in 1982 at UC Berkeley when he was chosen as an Una's Lecturer in the Humanities.

Baxandall's interests were broadly analytic and firmly tethered to the specific effects of context and experience on the mentality of the artist and his audience. This was an approach he shared with Svetlana Alpers, another of UC Berkeley's discipline-changing art historians and now a professor emeritus, who became his close intellectual collaborator for the rest of his life. They co-authored "Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence" about 18th-century Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. The 1994 book was widely acclaimed for its analyses of the phenomenology of drawing and invention.

Baxandall published "Shadows and Enlightenment" (1995) and "Words for Pictures" (2003). Both books continued his focus on the nature of sight and perception and its effect on the artist's practice and the audience's experience.

A group of distinguished art historians explored his work and its influence on contemporary cultural theory in "About Michael Baxandall," a special issue of the journal Art History in 1999.

Baxandall was awarded the Edmund Gardner Prize in 1972 for the best United Kingdom contribution to Italian studies between 1968 and 1972 and the Mitchell Prize in 1980 for best English language book on art. He was given a London University chair in 1981, was elected to the British Academy in 1982, received the city of Hamburg's Aby M. Warburg Preis in 1988, and also in 1988 was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship.

Former students remember his profound influence.

"As graduate students, we tended to turn over his responses to our papers and questions in our minds for hours after leaving his office," said Evelyn Lincoln, an associate professor of the history of art and architecture at Brown University in Providence, R. I., and one of Baxandall's Ph.D. students at UC Berkeley from 1989 to 1994.

"Often this was because it was hard to work out what he had actually said: He spoke quietly, often in single declarative words or short phrases rather than whole sentences, and with an unfamiliar accent that had to make its way around the ever-present cigarette between his lips, except when he was trying to quit smoking, in which case he was that much less given to relaxed conversation," Lincoln recalled. "As in his writing, those single words were deceptively simple statements, and so a conversation with Baxandall, no matter how short, could be depended on to change one's perspective about one's work in productive ways."

Robin Adéle Greeley, a former Baxandall student at UC Berkeley and now an associate professor of Latin American art history at the University of Connecticut, said his students were in awe of him.

"In addition to watching his own mind at work, our greatest privilege as his students was the manner in which he pushed us to reach beyond what we thought possible in both intellectual adventure and moral courage," Greeley said.

"One of his great abilities was to present us with precisely the right tantalizing fragment of insight such that we would ourselves do the work of scrambling up to the next level of intellectual enlightenment," she said. "We scrambled a lot, and found it exhilarating."

Nigerian novelist Teju Cole wrote a guest tribute to Baxandall for "the cassandra pages" blog, saluting what he called "trademark Baxandall: the patient, inductive tone, the crystalline language, the erudite undertow, all in the service of clarifying our words for images."

Baxandall is survived by his wife, Kay, of London; two children, Lucy and Thomas; and two grandchildren.