UC Berkeley Press Release

| A crowd gathered after a Navy blimp crashed to the streets of Daly City in August, 1942. Photo by Trudeau. (All photos courtesy the Bancroft Library) |  |

Bancroft exhibit focuses on SF Examiner photo archive

BERKELEY – "Twenty-five Years in Black & White," a slice of San Francisco Bay Area history from 1935 to 1960, just opened at the University of California, Berkeley, with more than 100 photos from the Bancroft Library's Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Archive.

The images depict the era at either end of World War II, the House of Representatives' Un-American Activities Committee hearings in the '50s held at San Francisco City Hall, Japanese-American internment, the Great Depression and migrant workers, the controversial Caryl Chessman execution, pro- and anti-Nazi rallies in San Francisco, labor unrest, the signing of the United Nations charter and an ever-vibrant arts scene.

The famous Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali and his wife, Gala, were photographed in Carmel in August, 1941. The Dalis moved to the United States after World War II broke out in Europe. Photo by Gomez. |

Jack von Euw, curator of the new exhibit in the Bernice Layne Brown Gallery of UC Berkeley's Doe Library and the pictorial curator for the Bancroft, said the exhibit offers an "unvarnished and unparalleled" look at Northern California history.

"These images are part of our history, visual testimony to quantum leaps in technology, the look of 'old' San Francisco, much of which has disappeared, the political investigations driven by the Cold War and opportunistic politicians playing on the fears of the citizenry," he said.

In addition to images of major news events, the exhibit chronicles celebrity sightings of stars like Marlon Brando protesting outside of San Quentin State Prison, opera diva Marian Anderson, Madam Chiang Kai-Shek arguing for United States support for China against Japan, and newlyweds Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe.

And there are "great pictures of ordinary people doing extraordinary things," said von Euw. One of his favorites is of workers at San Francisco's S&S Pie Co. Another is of the "Miss Victory Contest," whose winners were chosen by coworkers and managers in recognition of wartime efforts.

The exhibit categories of the war years and their aftermath, fame and fortune, crime and punishment, and people, politics and places fell into place as von Euw browsed the archive.

Ironically, many major issues of the era - immigration and racism, civil liberties and national security, and the death penalty - remain controversial today. "The personalities, the clothes and the technology changes, but the issues are really the same," said von Euw.

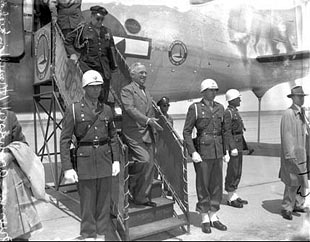

President Truman arrives in San Francisco in 1945 for the founding conference of the United Nations Photo by Meacham. |

Many exhibit images are being seen for the first time, except by the photographers as they snapped the shutters of their bulky, single-lens Graflex cameras, the favored news camera of the day. "So little of what the photographers shot was ever seen beyond the photo editor's desk," von Euw said. "We're looking at prints that have never been seen, even by the photographers themselves."

Von Euw said he appreciates the Graflex's large, sharp negatives, its big, bright flashbulbs and individual sheets of film. Graflex photographers had to carefully gauge the best time and place for a shot and hope they could scramble there quickly enough with all of their cumbersome gear, he said.

"The quality of their photos was quite fantastic when they could pull off a good shot," said von Euw.

In recognition of their skill, the exhibit identifies by name the photographers who took the shots. They weren't always identified in the newspaper, said von Euw, and even in the negative archives, they often are listed only by their last name.

Many Examiner archive prints are of photos by wire service photographers, and some were sold to and through commercial outlets. But the negatives are of photos taken by Examiner photographers and represent what von Euw considers the "heart and soul" of the collection.

He didn't doctor the negatives or clean up scratches to make the images look better because, he said, he wanted to illustrate the archive's fragility and the need for its preservation. The negatives were scanned and printed on color photographic paper with a LightJet process that gives them an original look, von Euw said.

The monumental task of re-housing prints and stabilizing the at-risk negatives has begun, but without additional funding for preservation, reformatting and cataloging, he said much of the archive will remain inaccessible for years to come.

The Examiner archive is about five times the size of the Bancroft's archive of the San Francisco Call Bulletin newspaper, which took about 20 years to catalog.

Anti-death penalty protesters marched outside the gates of San Quentin State Prison on May 2, 1960, the day that rapist and robber Caryl Chessman was put to death after eight stays of execution. Photo by Pardini. |

Ironically, von Euw said, the exhibit space is named for the wife of the late California Gov. Edmund G. "Pat" Brown, whose political career was nearly derailed by the Chessman case, which is well documented in the exhibit. Brown issued a 60-day stay of execution for Chessman, a convicted rapist and robber who became the center of a national campaign against the death penalty and steadfastly claimed that he was the victim of mistaken identification. Chessman's execution was delayed eight times before he was put to death in 1960.

The Bernice Layne Brown Gallery is on the first floor of Doe Library near the center of campus. The exhibit will be up until Feb. 28, 2009.