|

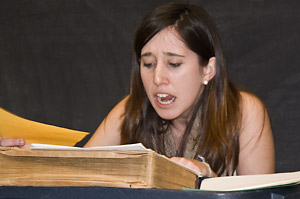

Cal debaters Kathy Bowen and Andres Gannon at the Cal Invitational Debates, held at Berkeley on Jan. 24-25. (Cathy Cockrell photo) |

Cal Debate's hard-working, high-powered verbal gladiators

| 29 January 2009

BERKELEY — For students Kathy Bowen and Jacob Polin, winter "break" was a chance to cram non-stop for the high-stakes contests of brains and strategy awaiting them in January.

Fast talk: Long ago, high school and college debaters made their arguments at conversational speeds and were judged on eloquence and persuasion. In the 1960s, a new style of debate was introduced. Judges began to reward research, information, and logic, and debaters — employing a technique they called "spreading" — began to speak at ever-increasing rates, up to an astonishing and barely understandable 400 words per minute.

A recent HBO movie, "Resolved," documents

a recent controversy (on the high school debate scene)

about spreading and other aspects of the intellectual

strategy sport.

For many, the fast talk is a boon. Cal debater Kathy Bowen believes that having to think critically and speak persuasively at high RPMs only "elevates the game" — making it "more educational and more challenging."

"Students talk fairly quickly because they have a lot to say," concurs Greg Achten, Cal Debate co-director. "They've done a lot of research and they have limited time."

They're not crazy. But they are members of Cal Debate, UC Berkeley's intercollegiate policy debate team, which has competed at the upper echelon of the intellectual sport for close to a decade. At that level, "you need to be putting three hours a day into research," says Bowen, a sophomore political science major. "It's a year-round process that's most intensive in summer."

That's when officials of the national Cross Examination Debate Association announce the topic for the coming year — always on a controversial national or international policy issue — launching college debaters headlong into R&D. In the dog days of summer, with gigabytes of information already on their laptops, they hold strategy sessions on how to frame their arguments — both "affs" and "negs," since they'll have to argue both sides of the resolution. By early September, they test their mettle in the season's first match-ups.

Sudden experts on subsidies

This year, college policy debaters (versus parliamentary debaters, who practice a separate but related forensics activity) have been sparring over a resolution calling for the U.S. government to substantially reduce its agricultural subsidies. The commodities in question run the gamut from biofuels to wheat, each complex in its own way — so Cal Debate has divvied up the research load

Polin, a junior majoring in political science, is now a walking encyclopedia on the cotton industry and the federal subsidies that support it. One of the "cooler weirdities" he discovered in his digging is that "there's more cotton in the food supply than in clothes. They grind it up to make a bunch of different foods," he says, yet it's treated with chemical pesticides as if none of it were destined for our stomachs.

In Polin's experience as a debater (seven years, including high school), strategy is critical. So he and his peers spend a lot of time trying to anticipate competitors' arguments — and how those arguments may change as the season proceeds. So far this year, many colleges have chosen to emphasize the impact of U.S. subsidies on world food prices. In contrast, Polin reports that he and his debate partner, Michael Burshteyn, decided over the summer that "our strength was talking about international law — the WTO talks we're not living up to" by artificially supporting agricultural commodities.

Cal Debate's storied resurrection

Their strategic approach has proven sound. At January's Dartmouth Round Robin — an invitational tournament for the nation's top seven teams — Polin and Burshteyn came in second. And last spring they earned one of college forensic's highest honors, the Copeland Award, given to the two-person debate team with the year's best record. It was Cal's third Copeland in seven years, and one more indication, if any were needed, of the team's remarkable and meteoric rise from mediocrity to greatness.

Before 2000, no university west of the Mississippi had ever taken home a Copeland. "It was awarded to the Harvards, the NYUs, the Emorys and the Northwesterns," recalls Marv Levin, of Walnut Creek, who spent his undergraduate years on Berkeley's debate squad, before earning a law degree at Boalt in 1955. When Levin learned, in the late '90s, that his alma mater's debate program was in the pits, he joined forces with fellow alum Barclay Simpson to help resuscitate the program. For starters they helped the campus recruit Dave Arnett, a coach who was making a name for himself at the University of Kentucky, and Tejinder Singh, one of the top high school debaters in the country.

The alums' intervention changed everything. Under Arnett's leadership, Berkeley rose, in four years' time, from 127th in the nation (out of 150) to number one — in the process breaking private institutions' stranglehold on the game's highest honors. Singh's presence on the team helped attract other stellar high school debaters, beginning with Dan Shalmon — who as a freshman earned UC Berkeley's first Copeland Award, with Randy Luskey. In 2003-04, Shalmon and Singh earned its second. (At the first official Cal Debate reunion, Shalmon gave a keynote address on the national impact of the Cal Debate's renaissance and, on a personal note, how he has brought his forensics experience to his struggle with Hodgkin's Disease.)

"Our conception of what was possible really changed once Randy and Dan won the Copeland," recalls Singh, who graduated last spring from Harvard Law School. (Most Berkeley debaters go on to law school. "Understanding the anatomy of an argument transfers readily to law," notes Singh. In the courtroom, as in life, "whatever position you're taking, ask yourself what is the best argument against it. A lot of people don't consider this. Every debater has — and they know their best answer.")

Working for the team

Cal Debate's verbal gladiators attend eight to ten tournaments a year, nearly all involving plane travel followed by three intense, 12- to 13-hour days of forensic warfare. "Once you've lost, that's not the end of the tournament," Kathy Bowen says of the team culture. "You work for the team" — doing eleventh-hour research for teammates still in the running — "and we celebrate our successes together."

Cal debaters Jacob Polin and Mike Burshteyn (second and fifth from left) celebrate their 2008 Copeland Award with Cal Debate coaches Dave Arnett (left) and Greg Achten (third from left) and former Cal assistant coach Dan Fitzmier. |

Though no pair of Cal debaters is on course to win the 2009 Copeland, Polin believes that the team as a whole is in a strong position entering the season's final lap. Last year it finished 9th at the year's culminating event, the National Debate Tournament. "We think we're a lot better" now, he reports. So their sights are set on an NDT win. "That's our goal. Austin, end of March," says Polin. "We're pouring all of our energies into that endeavor."

So much for spring vacation. But matching wits with the nation's best and brightest is a ton of fun to its rare breed of practitioners — "a mental challenge so rigorous," in Bowen's words, that success is sweet, and makes up for the sacrifices. "There's no way I'd be willing to do this," says Polin, if tournament competition were not "unbelievably awesome."