Assembling cells into artificial 3-D tissues, like tiny glands

| 04 March 2009

BERKELEY — As synthetic biologists cram more and more genes into microbes to make genetically engineered organisms produce ever more complex drugs and chemicals, two University of California chemists have gone a step further.

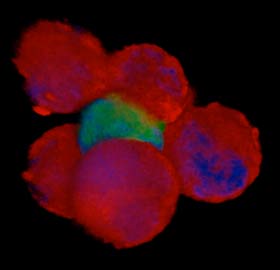

A 3-D reconstruction using deconvolution fluorescence microscopy of a single multicellular structure encapsulated in agarose gel. Cells are stained different colors according to the oligonucleotide sequence attached to their surfaces. (Bertozzi lab/UC Berkeley images)

A 3-D reconstruction using deconvolution fluorescence microscopy of a single multicellular structure encapsulated in agarose gel. Cells are stained different colors according to the oligonucleotide sequence attached to their surfaces. (Bertozzi lab/UC Berkeley images)"This is like another level of hierarchical complexity for synthetic biology," said coauthor Carolyn Bertozzi, UC Berkeley professor of chemistry and of molecular and cell biology and director of the Molecular Foundry at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "People used to think of the cell as the fundamental unit. But the truth is that there are collections of cells that can do things that no individual cell could ever be programmed to do. We are trying to achieve the properties of organs now, though not yet organisms."

While the synthetic tissues today comprise only a handful of cells, they could eventually be scaled up to make artificial organs that could help scientists understand the interactions among cells in the body and might some day substitute for human organs.

"We are really taking this into the third dimension now, which for me is particularly exciting," said first author Zev J. Gartner, a former UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow who recently joined the UC San Francisco faculty as an assistant professor of pharmaceutical chemistry. "We are not simply linking cells together, we are linking them together in 3-D arrangements, which introduces a whole new level of cellular behavior which you would never see in 2-D environments."

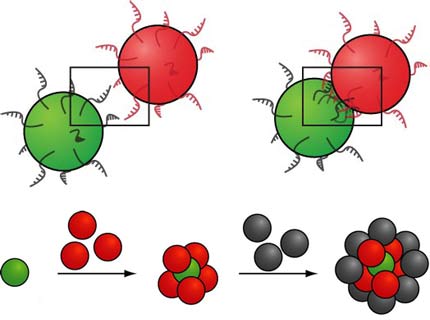

Short, complementary strands of DNA (oligonucleotides) are attached to two different cells and hybridize to bring the cells into physical contact. By using different complementary DNA strands, it is possible to build microtissues of three or more cell types.

Short, complementary strands of DNA (oligonucleotides) are attached to two different cells and hybridize to bring the cells into physical contact. By using different complementary DNA strands, it is possible to build microtissues of three or more cell types. One type of cell that needs other cells to make it work properly is the stem cell, Bertozzi noted. Theoretically, using Gartner and Bertozzi's chemical technique, it should be possible to assemble stem cells with their helper cells into a functioning tissue that would make stem cells easier to study outside the body.

"In principal, we might be able to build a stem cell niche from scratch using our techniques, and then study those very well defined structures in controlled environments," Bertozzi said.

Bertozzi noted that most of the body's organs are a collection of many cell types that need to be in actual physical contact to operate properly. The pancreas, for example, is a collection of specialized cells, including insulin-secreting beta cells, that "sense glucose from the environment and respond by producing insulin. A complex feedback regulatory loop goes into all of this, and you need more than one cell type to achieve such regulation."

"If you really want to understand the way these cells behave in an organism, especially a human, you would like to recapitulate that environment as closely as possible in vitro," Gartner said. "We are trying to do that, with the aim that the rules we learn may help us control them better."

Clusters of cells could be joined to build larger tissues, like this double cluster.

Clusters of cells could be joined to build larger tissues, like this double cluster.To get these specific DNA strands onto the cells, they used chemical reactions that do not interfere with cellular chemistry but nevertheless stick desired chemicals onto the cell surface. The technique for adding unusual but benign chemicals to cells was developed by Bertozzi more than a decade ago based on a chemical reaction called the Staudinger ligation.

After proving that they could assemble cells into microtissues, Gartner and Bertozzi constructed a minute gland - analogous to a lymph node, for example - such that one cell type secreted interleukin-3 and thereby kept a second cell type alive.

"What we did is build a little miniaturized, stripped-down system that operates on the same principle and looks like a miniaturized lymph node, an arrangement where two cells communicate with each another and one requires a signal from the other," she said. "The critical thing is that the two cells have to have a cell junction. If you just mix the cells randomly without connection, the system doesn't have the same properties."

She expects that eventually, clusters could be built on clusters to make artificial organs that someday may be implanted into humans.

"Our method allows the assembly of multicellular structures from the bottom up. In other words, we can control the neighbors of each individual cell in a mixed population," she said. "By this method, it may be possible to assemble tissues with more sophisticated properties."

One interesting aspect of the technique is that DNA hybridization seems to be temporary, like a suture. Eventually, the cells may substitute their own cell-cell adhesion molecules for the DNA, creating a well-knit and seemingly normal, biological system.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy as well as the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Gartner was supported by a fellowship from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund.

See related story at LBNL's News Center, "Cellular engineers make multicellular tissues from the bottom up."