Inexpensive flooring change improves child health in urban slums

| 10 March 2009

BERKELEY — Replacing dirt floors with cement in the homes of urban slums makes for more comfortable living - but more importantly, it significantly improves children's health by interrupting the transmission of intestinal parasites and boosts youngsters' cognitive abilities, according to a new study conducted for the University of California, Berkeley's Center of Evaluation for Global Action (CEGA).

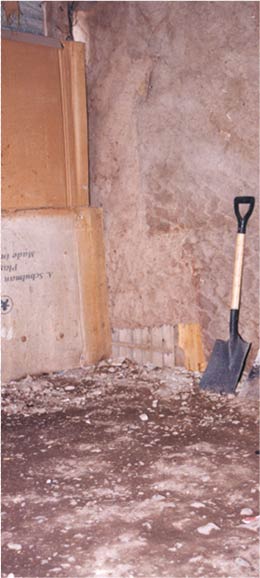

Dirt floors facilitate the spread of parasitic illness. (Photos courtesy Center of Evaluation for Global Action)

Dirt floors facilitate the spread of parasitic illness. (Photos courtesy Center of Evaluation for Global Action)Not only are young children better off when their homes have concrete rather than dirt floors, but the study also found that their mothers are less depressed, less stressed and happier.

"The reasons adults are happier may have to do with the fact that they are living in a better environment and that their children are healthier," says the report. "These results also indicate that housing has a significant effect on welfare, which would not be captured by standard monetary indicators such as income, consumption or assets, or by the types of health outcomes used in this study."

The CEGA researchers note that inadequate housing poses serious health risks around the globe for 600 million urban residents, almost half of them living in slums. These problems also contribute to the deaths of 3 million children every year from parasitic infections associated with diarrhea, malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies such as anemia, a widespread problem that slows cognitive development.

The economists say their findings offer an important direction for the cost-effective allocation of public resources by countries seeking to upgrade slums and improve housing for the poor.

They tracked a Mexican government program, "Piso Firme" or "firm floor," that sought to improve living standards and health in high-density, low-income communities by offering homeowners with dirt floors up to 538 square feet of concrete flooring. The program cost the government about $150 per home. The owners prepared and laid the new flooring themselves, or with volunteer help.

Concrete trucks line up to deliver new flooring material to poor homeowners.

Concrete trucks line up to deliver new flooring material to poor homeowners.Mexico launched Piso Firme in the northern state of Coahuila in 2000. By 2005, the program had covered more than 34,000 homes in 650 neighborhoods and 200 suburban communities. It expanded into other Mexican states starting in late 2003 and installed cement floors in about 300,000 of the 3 million homes identified in the country's 2000 census as having dirt floors.

Researchers collected information about children's incidences of diarrhea, results of fecal samples, blood tests for anemia, and height and weight data to reveal stunting of growth, and also assessed the youngsters' communication and language abilities. They compared the statistics for youths under the age of 6 both in the Coahuilan city of Torreón, where Piso Firme was enacted, and in the cities of Gómez Palacios and Lerdo in the same urban area but located on Coahuila's border with state of Durango, where Piso Firme was still not fully under way in 2005.

Additional data came from a cross-sectional household survey conducted with the Mexican National Institute of Public Health in spring 2005, the 2000 Mexican census, vital statistics mortality files and national household surveys taken from 1994 to 2000.

Homeowners in Torreón reported a nearly 20 percent reduction in the presence of parasites, and when compared to their neighbors, their children under the age of 6 showed the following improvements:

- Almost 13 percent fewer episodes of diarrhea

- A 20 percent reduction in incidences of anemia

- Higher scores of 30 percent on language and communication skills for toddlers ages 12 to 30 months

- Scores 9 percent higher on vocabulary tests for youths ages 36 to 71 months

An elderly woman prepares a room with a dirt floor for its concrete replacement.

An elderly woman prepares a room with a dirt floor for its concrete replacement.The researchers caution that the dirt-to-cement strategy probably would not have the same results in rural areas without access to safe water supplies.

The research team included Gertler, who is the director of UC Berkeley's Institute for Business and Economics Research and recently served as the chief economist of the World Bank's Human Development Network; Rocío Titiunik, a UC Berkeley graduate student in agricultural and resource economics; Sebastián Martinez, a World Bank economist who earned his Ph.D. in economics at UC Berkeley; Sebastian Galiani, an associate professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis; and Matias Cattaneo, an associate professor of economics at the University of Michigan who also earned his Ph.D. at UC Berkeley.

CEGA's interdisciplinary team of researchers advances global health and development through impact evaluation and economic analysis. It works with collaborators in more than 20 countries in the developing world, often in partnership with academic institutions in the southern hemisphere that create hands-on research experiences for hundreds of local investigators and strengthen local research capacity.