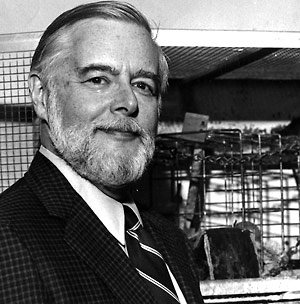

Mark Rosenzweig, pioneer in brain plasticity, learning and hearing, has died at 86

| 03 August 2009

BERKELEY — Mark R. Rosenzweig, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, whose early studies paved the way for today's recognition of the brain's ability to grow and repair itself, died July 20 at his home in Berkeley from kidney failure. He was 86.

Mark

Rosenzweig

Mark

Rosenzweig

A prolific researcher, writer and French-speaking internationalist, Rosenzweig collaborated with some of the greatest minds in neuropsychology at Harvard University, UC Berkeley and the Louis Pasteur University in Strasbourg, France.

At UC Berkeley, Rosenzweig collaborated with biochemist Ed Bennett, psychologist David Krech and neuroanatomist Marian Diamond on studies that provided early evidence of brain plasticity - the now-well established notion that neural pathways change throughout our lives as we grow and learn. In addition, his earlier research into auditory perception also laid the groundwork for modern, noninvasive hearing tests.

"Rosenzweig's investigations were rigorous, groundbreaking and continue to be cited in all current accounts of brain development and plasticity, though they were conducted half a century ago," said Stephen Hinshaw, chair of UC Berkeley's Department of Psychology. "If anyone deserves the term 'pioneer,' he does."

Through extensive studies of laboratory rats at UC Berkeley in the 1950s and '60s, Rosenzweig and his colleagues were able to show that "environmental therapy" can stimulate brain growth at a cellular level not only in children, but also in adults. For example, he found that rats living in an "enriched environment" with stimulating interactive tasks performed better at learning activities than those in passive, impoverished conditions.

Early life

A descendent of Lithuanian and Russian Jews who came to America in the 1880s, Rosenzweig was born in Rochester, New York, on Sept. 12, 1922. His father was a lawyer and his mother a homemaker who was bilingual in English and German. In an autobiography published in the 2006 book, "The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography, Volume 5," Rosenzweig described a warm, stimulating upbringing in which his parents fostered a love of languages and cerebral activities, playing word games with their son and daughter to improve their vocabulary.

He attended public schools in Rochester and was selected class valedictorian in both grammar school and high school. In 1940, he entered the University of Rochester, and while he started out drawn to history, his fascination for psychology won out. In 1943, he earned a bachelor's degree in psychology and in 1944 went on to earn a master's degree, specializing in the brain mechanism of auditory perception.

In 1944, he was drafted into the U.S. Navy and stationed at the Anacostia Naval base in Washington, D.C., where he was a radar technician. When President Roosevelt died in 1945, Rosenzweig marched in the funeral procession. Later, he shipped out across the Pacific Ocean to Tsingtao Harbor in China and was stationed on the USS Chincoteague, a seaplane tender..

After being discharged from the Navy in 1946, Rosenzweig was accepted to Harvard where he worked in the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory. In his 1949 doctoral thesis, he demonstrated that electrodes placed on the skull could pick up "electrical activity of all the auditory stations from the cochlea to the cortex." This meant that the "activity of subcortical centers can be studied without surgical invasion of the nervous system," he later pointed out. In the 1970s, his method of testing stations of the auditory system via the surface of the brain was developed to identify newborn babies with hearing loss.

At Harvard, he met Janine Chappat, a French-born scholar of education and cultural anthropology who had been studying at the University of Oxford when the war brought her to the United States. They married in the summer of 1947 and went on to have three children, Anne Janine, Suzanne Jacqueline and Philip Mark. The family spoke only French at the dinner table.

"Our father's dedication to science was matched by his devotion to his family," said his daughter, Suzanne Washburn. "He enriched our lives through education, travel and laughter."

Career at Berkeley

In 1949, Rosenzweig was offered an assistant professorship in physiological psychology at UC Berkeley. At the time, all UC employees were required to sign a controversial anti-communist loyalty oath that made Rosenzweig wary about taking the job. But, he wrote in his autobiography, Professor Edward C. Tolman, for whom UC Berkeley's psychology department building is now named, told him, "If you are interested in the position, take it. There are enough senior professors to maintain the fight against the loyalty oath and we don't want to cripple the future of the university by stopping recruitment of young people."

At UC Berkeley, Rosenzweig continued his investigation into "binaural perception," but soon he and his colleagues became drawn to the study of learning and memory, and began their investigations of the brain: "Our first reports that differential experience induces measureable changes in the brain were greeted with skepticism and incredulity," he wrote. But in later years, the researchers' findings gained acceptance.

"We did not invent the concept of the 'enriched environment,' but I believe that our publications introduced the concept and the term to the neuroscience community," he wrote. In 1982, Rosenzweig received the American Psychological Association's Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions for his research demonstrating that weight, chemistry and ultrastructure of brain components are affected by environmental stimulation.

A strong supporter of public education and equal opportunity, Rosenzweig and UC Berkeley physics Nobelist Owen Chamberlain in 1964 were co-chairs of the Special Opportunity Scholarship Committee, designed to prepare underprivileged high school students for university education. Their initiative developed into the federal program known as Upward Bound.

Another of Rosenzweig's passions was the international teaching of psychology, and he became heavily involved in the International Union of Psychological Science, for which he served as president from 1988-92.

Among other accolades, Rosenzweig won the Berkeley Citation in 1992 and the American Psychological Association's Contribution to International Psychology Award in 1998. He also received honorary doctorate degrees from the Université Rene Descartes in Paris, the Université Louis Pasteur in Strasbourg and the Université de Montreal. He served as editor of the journal Annual Review of Psychology from 1968-94. He was also elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

He retired from UC Berkeley in 1991 and was rehired as a professor of graduate studies in 1994. "He was a formal old-fashioned gentleman, very witty, and always gentle and friendly," said Donald Riley, a professor emeritus of psychology at UC Berkeley and a colleague and longtime friend of Rosenzweig's.

"Behind Mark's reserved formal exterior, there was an impish sense of humor, which emerged with a special smile," said Stephen Glickman, UC Berkeley professor emeritus of psychology and of integrative biology.

Rosenzweig is survived by his daughters, Anne Janine Rosenzweig of Morgan Hill, Calif.; Suzanne Jacqueline Washburn of Moraga, Calif.; son, Philip Mark Rosenzweig of Sedbergh, England; sister, Patty Epstein of Green Valley, Ariz.; six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his wife, Janine, who passed away in 2008.

A memorial service will be held at 3:30 p.m. on Friday, Sept. 11, at the UC Berkeley Faculty Club. For more details about the event, and on how to make donations to a scholarship in Rosenzweig's name for graduate research in biological psychology, contact Frances Katsuura, director of administration at the UC Berkeley Department of Psychology, at (510) 642-7074 or katsuura@berkeley.edu.