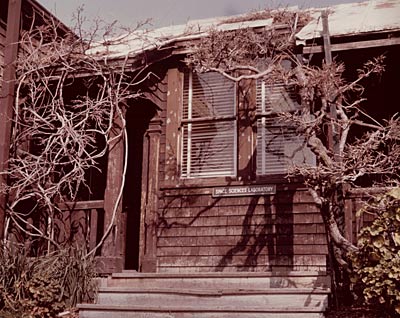

| Until 1966, the main offices of the Space Sciences Laboratory were in the old Leuschner Hall, site of the university's first observatory on Observatory Hill, just north of the new C.V. Starr East Asian Library. |  |

Space Sciences lab celebrates 50 years & 75 satellites

| 28 August 2009

BERKELEY — In 1959, only two years after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik and ignited the space race, the University of California, Berkeley, created a laboratory devoted to space science that has grown to be one of the most active academic space research labs in the country.

The Space Sciences Laboratory, later named the Samuel Silver Space Sciences Laboratory, overlooks Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the UC Berkeley campus. (SSL photo)

The Space Sciences Laboratory, later named the Samuel Silver Space Sciences Laboratory, overlooks Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the UC Berkeley campus. (SSL photo)"The University of California at Berkeley showed its greatness when it founded the Space Sciences Laboratory at the very dawning of the space age, only a year after NASA was created," said Charles F. Kennel, former director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and a member of the NASA committee now debating the future of human space flight. Kennel, who directed NASA's Mission to Planet Earth from 1994 to 1996, will be the keynote speaker at a banquet this Saturday (Aug. 29) celebrating the lab's anniversary.

"The laboratory more than fulfilled the vision of its creators," he added. "Under distinguished directors, from Sam Silver to Bob Lin, SSL conducted world-leading experimental research in solar system plasma physics and astrophysics. Recently, the laboratory was the first at a university to design, build and manage an entire spacecraft project (THEMIS). It is poised to take the next great leap into space."

Currently, the lab is mission control for the THEMIS suite of five space probes exploring the Earth's magnetic field and the RHESSI satellite, which studies solar flares and the sun's coronal mass ejections. These satellites are key members of the network of satellites that NASA has launched to monitor space weather and learn how to predict the atmospheric fireworks that can damage communications satellites and endanger astronauts. SSL will also be mission control for NASA's NuSTAR mission, scheduled for launch in 2011, which will focus and image X-rays emissions from black holes.

"The Space Sciences Laboratory has risen to become the premier academic institution in the world for atmospheric, ionospheric, auroral, magnetospheric, planetary, interplanetary, solar, astrophysics and cosmology research," said physicist Forrest Mozer, a UC Berkeley professor of the graduate school who organized the Aug. 29-30 anniversary symposium. "No other university has been at the forefront of so many different fields of space science."

These five THEMIS spacecraft constitute the first multi-satellite mission built at a university and the first time that five major scientific spacecraft were launched on a single vehicle. Launched Feb. 17, 2007, all five spacecraft have operated without a single failure. (NASA photo)

These five THEMIS spacecraft constitute the first multi-satellite mission built at a university and the first time that five major scientific spacecraft were launched on a single vehicle. Launched Feb. 17, 2007, all five spacecraft have operated without a single failure. (NASA photo)"SSL puts a strong emphasis on student training," said SSL Director Stuart Bale, associate professor of physics. "Our graduate students really get their hands dirty designing and building space experiments, which gives them a big edge when they enter the job market. This student involvement, which includes many undergraduates, really sets us apart from most other big space science laboratories, such as NASA centers."

Recent projects by SSL scientists include a far ultraviolet detector built for the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS), which was installed on the Hubble Space Telescope in May, and instruments to be sent to Mars on the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) satellite. Another instrument is destined for Earth's orbit aboard the Radiation Belt Storm Probes mission, which will study our planet's radiation belt.

"It's fortunate that, once our missions are up there, they work great and they last forever," said physicist Robert Lin, who stepped down this year after serving as SSL director for 10 years.

Lin, who is principal investigator for the 8-year-old RHESSI mission, was involved in building an electron reflectometer/magnetometer instrument for the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft that first detected a magnetic field on the surface of Mars and evidence of an aurora similar to Earth's Northern Lights. That instrument operated for 10 years before the orbiter died in 2006.

Lin and his colleagues are now developing 8-pound, 12-by 4-by 4-inch microsatellites - referred to as CubeSats - that can piggyback on other missions and, once in space, link up by the dozen in a "constellation." SSL scientists and engineers also are collaborating with UC Berkeley physics professor Saul Perlmutter, a former SSL senior fellow and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory scientist, on the design of a proposed Joint Dark Energy Mission (JDEM) to precisely measure the expansion of the universe.

Although approved by the UC Regents in 1959 with an initial budget of $50,000, SSL didn't really get off the ground until 1961, when NASA awarded the lab a CORE grant of $741,000 over three years, which supported some 50 research projects. In 1962, NASA gave the university another $1.9 million - one of the first grants awarded by NASA to build research facilities at a university - to construct a building in the hills above the campus.

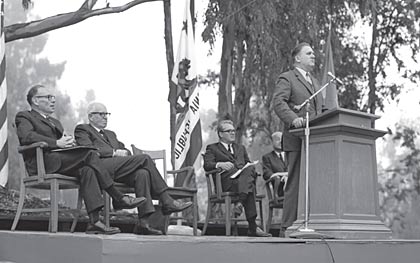

James Webb, NASA's first administrator, addresses attendees at the dedication of the Space Sciences Laboratory in 1966. Seated from left to right are Samuel Silver, the first director of the lab, Congressman George Miller Sr., UC Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns and UC President Clark Kerr.

James Webb, NASA's first administrator, addresses attendees at the dedication of the Space Sciences Laboratory in 1966. Seated from left to right are Samuel Silver, the first director of the lab, Congressman George Miller Sr., UC Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns and UC President Clark Kerr. NASA administrator James Webb, for whom the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope is named, attended the dedication of the new building in 1966, sitting beside UC President Clark Kerr, UC Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns and SSL's first director, Samuel Silver. The building was named after Silver, a professor of electrical engineering, upon his death in 1976. A second research building was completed in 1998 at a cost of $14.5 million.

The first work conducted by the lab was on space physiology, reflecting NASA's emphasis at the time on health, life and social science research in preparation for its "Man in Space" program, Mozer said. Chemist and Nobelist Melvin Calvin investigated chemical evolution and exobiology, while radiation biologist Hardin B. Jones studied the effects of the "space environment" on the body.

Physics professor Kinsey Anderson, who became director in 1970, instituted the first space physics programs in 1960, developing experiments to be carried above the ground by balloons, rockets and, eventually, satellites. His first satellite experiment, to study hot ion plasmas in space, went up in 1963 aboard the International Monitoring Platform (IMP1). With subsequent satellite experiments, such as those aboard the now-defunct FAST satellite and the still-active Polar, Wind, Cluster, STEREO and THEMIS missions, SSL scientists have continued studies of ion flow in the Earth's magnetosphere, which trigger the brilliant Northern and Southern Lights. Instruments on other satellites, including STEREO and RHESSI, focus on magnetic processes in the sun and in the heliosphere.

Planetary missions started with chemist George Pimentel, who worked with engineers at SSL to build an infrared spectrometer for the Mariner Mars spacecraft, launched in 1969. Designed to determine the chemical constituents of the Martian surface, the experiment failed in one respect: It could find no evidence of water on the planet. Later, Lin built instruments for the Lunar Prospector and Mars Global Surveyor, and now for MAVEN.

In 1992, astronomer Stuart Bowyer pioneered observations of the sky in the extreme ultraviolet with the launch of the UC Berkeley-built and -operated EUV Explorer satellite. Subsequent satellites have carried EUV, far UV, X-ray, gamma-ray, electron and magnetic field detectors into space. SSL's longest-running project is a ground-based Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence that Bowyer began in 1976 and which continues today with instruments mounted on Puerto Rico's Arecibo Radio Telescope. SSL also is home to the 10-year-old SETI@home project that enlists volunteers in the analysis of radio data from Arecibo.

SSL scientists have led cosmology experiments, starting with George Smoot's work on the COBE satellite in the 1980s. In 1989, Smoot as an SSL fellow finally saw COBE's launch, and celebrated its first detection of the tiny temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, which earned him the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics. Other SSL researchers are now searching through cosmic dust from NASA's Stardust mission for evidence of the origins of cosmic rays and through solar material from NASA's Genesis mission to determine the flux of radionuclides from the sun.

With more than $50 million in funding from NASA and the National Science Foundation last year, SSL brought in about 10 percent of all overhead received by the campus, Mozer noted. Space physics continues to dominate SSL research, with nearly half of the lab's approximately 350 employees dedicated to research on the physics of the sun, heliosphere and the planets.

Obviously, SSL's success hinges on NASA's continued support for satellite missions, and Bale and Lin are optimistic that the agency and the public will continue to support space science research.

"NASA has a lot of exciting space science opportunities on deck for the near future, and SSL scientists are very well poised to get involved," Bale said.

Lin agreed, adding, "UC Berkeley continues to have a pile of great new ideas and, given reasonable circumstances, the Space Sciences Laboratory will continue to flourish and do great science."