Berkeley's Allan C. Wilson, the world authority on 'molecular evolution,' is dead at 56

| 22 July 1991

BERKELEY — Allan C. Wilson, a scientist who revolutionized the field of evolutionary biology with his work employing protein and DNA sequences as "molecular clocks" to chart the evolution of life on earth, died Sunday (7/21/91) in Seattle at the age of 56.

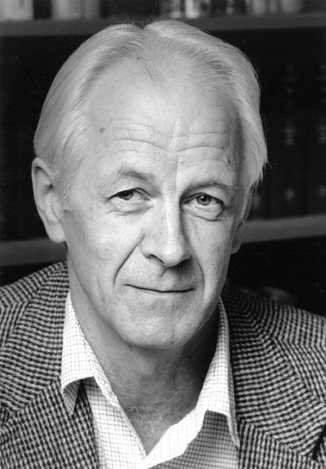

Allan Wilson (Jane Scherr photo, 1990)

Allan Wilson (Jane Scherr photo, 1990)Wilson, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California at Berkeley, suffered from leukemia. He died after receiving a bone marrow transplant June 17 at the Fred Hutchinson Memorial Cancer Center in Seattle.

A past winner of a MacArthur "genius" award, Wilson was known for his controversial hypothesis that proteins and genes can change over time at a steady rate. They thus could serve as a molecular clock to indicate the time since different species had a common ancestor.

"Before, evolutionary relationships were deduced from anatomical comparisons," said Berkeley collaborator Vincent M. Sarich. "The idea of the molecular clock has really changed the game in the past 25 years, providing an independent measure of these relationships. Allan was a very effective spokesman, but at the same time a demanding critic, of this approach."

Added Thomas Jukes, Berkeley professor of integrative biology: "He has had a very wide impact on the field, because of his new and innovative ideas, and also through the many students he trained in the area."

Wilson embarked on his major work nearly 25 years ago when he decided to tap into one of the richest sources of information on human history, our genes. Because genes and their building blocks, DNA, are the blueprint of life, they contain evidence of how life evolved over the eons.

He concentrated first on proteins, which directly reflect the DNA sequence of our genes, and showed that they can act as a molecular clock. Based on this clock, he and Sarich proposed in the late 1960s the now-accepted theory that apes and humans evolved from lineages that split off from one another approximately five million years ago.

Wilson has since used proteins and the genes themselves to piece together the genealogic relationships among various living and extinct animals. He cloned, for example, DNA from the extinct zebra-like quagga of South Africa, and looked at preserved protein from the frozen remains of a Siberian mammoth.

For the past 10 years he and his colleagues have concentrated on DNA in the mitochondria, an energy-producing organ inside every cell that contains its own complement of genes separate from the genes in the nucleus of the cell. These mitochondrial genes are inherited only from the mother.

Based on an analysis of mitochondrial DNA from people of various races, he and his colleagues in 1987 hypothesized that all humans living today have mitochondria traceable to a common ancestor who lived around 200,000 years ago in an African population.

The actual existence of Eve, "the mother of us all," is still a topic of debate among scientists.

In addition to his principal work on the mechanisms of evolution and how molecules evolve, he and his Berkeley colleagues also have been scouring museum collections for preserved plant and animal material whose DNA can be analyzed to trace the history of animal and human populations.

Other aspects of his work include the proposal that changes in the structure of genes and in their regulation are important in the evolution of animals.

Born in Ngaruawahia, New Zealand (10/18/34), Wilson joined the Berkeley faculty in 1964, and was appointed a full professor in 1972. He obtained his PhD from Berkeley in 1961 and conducted postdoctoral work at Brandeis University before returning to U.C. as an assistant professor.

He was appointed a MacArthur Fellow in 1986, and was a Guggenheim Fellow twice during his career. He received numerous other honors and awards, most recently the 1991 3M Life Sciences Award from the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. Wilson was an elected fellow of the Royal Society of London, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Achievement, and the Human Genome Organization.

He also was an associate editor of the Journal of Molecular Evolution, which is planning a memorial edition in his honor.

Wilson, who lived in Berkeley, is survived by his wife, Leona Wilson, and two children, Ruth, 30, of East Lansing, Michigan, and David, 27, of San Francisco.