|

HOME | SEARCH | ARCHIVE |

|

07 February 2001 | The following accounts were drawn from the Regional Oral HIstory Office's "Black Alumni Series," located in the Bancroft Library. The series documents the experience and accomplishments of distinguished African-american graduates from 1920-1956, a period in which black students and faculty enjoyed no special programs that might guide them or serve as role models.

Ida Louise Jackson 1903-1996

| |

Ida Louise Jackson |

Ida Louise Jackson once wrote: "The biggest people with the biggest IQs can be shot down by the smallest people with the smallest minds. Think big anyway." And think big is exactly what Jackson did.

Her father, a former slave, said the key to solving racial problems was for blacks to get better educated. So he sent his daughter off to Berkeley in 1920, where she was one of only nine black students.

Taking the Telegraph Avenue streetcar to campus each day, Jackson impressed her teachers and fellow students with her intelligence and drive. While here, she started an Alpha Kappa Alpha chapter, the first black sorority at Berkeley and in the western United States.

Proud of her newly formed group, Jackson and her sorority sisters scraped together $45 to get their photo in the Blue and Gold yearbook. Their picture was taken, but it never appeared.

Furious, she went straight to President David Barrows for an explanation. He told her the sorority "was not representative of the student body," so their picture was excluded.

While Barrows was not sympathetic to her cause, she had a true advocate in the dean of the School of Education, William Kemp, who helped her get a job as dean of women at Tuskegee University.

During that time, she helped establish a summer school in Mississippi to train black teachers and a mobile health care program to assist child workers in the cotton fields.

Returning to California in 1925, she became the state's first black teacher. She retired in 1955 as principal of McClymonds High School in Oakland.

Lionel Wilson 1915-1998

| |

Lionel Wilson |

Lionel Wilson spent much of his youth on the playgrounds of Oakland honing his athletic skills. But when he entered Berkeley in 1932, one of only a handful of black male students on campus, he wasn't allowed to join the basketball or baseball teams, the two sports at which he excelled.

"There was a great deal of discrimination here," Wilson said in his oral history. Berkeley, like many universities during this time, excluded African Americans from most sports teams.

Academically, Wilson was fairing much better, juggling the tough classes he needed for his economics major while working as a porter, dishwasher and sugar factory laborer to support himself.

But when it came time to ply his skills in the real world, racism would once again rear its ugly head. Upon completing a graduate class in personnel administration, the professor told Wilson apologetically, "I'll be able to place everyone in the seminar, but I won't be able to place you," referring to possible job opportunities.

Despite these kinds of setbacks, Wilson, who graduated from Berkeley in 1939, received his law degree from UC Hastings and went on to become Alameda County's first black judge and Oakland's first black mayor, elected to three consecutive terms, beginning in 1977.

Archie Williams 1915-1993

| |

|

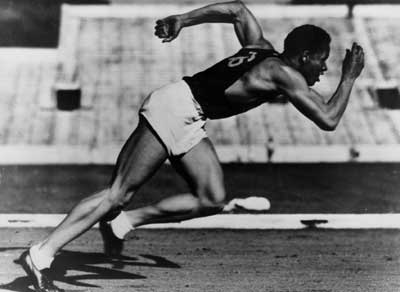

Unlike his classmate Lionel Wilson, Archie Williams was able to pursue his athletic passion at Berkeley. While the coaches for baseball, football and basketball excluded blacks, Brutus Hamilton, the track and field coach, showed no prejudice towards his runners.

"He showed a lot of interest in me as a student and an athlete," said Williams in his oral history. "We had to get good grades to be able to run."

Though Williams came to Berkeley primarily for an education - he was fascinated with airplanes and majored in mechanical engineering - he signed up for the team because he had done competitive running in junior college.

Within six months of his arrival at Berkeley, Williams won the NCAA championship in the 400-yard dash, then a gold medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in the same event. The black athletes, ironically, were treated very well in Germany, Williams said. "We didn't have to ride in the back of the bus there."

A serious hamstring tear ended Williams running career, but he pursued his academics with the same vigor. But even in the academic realm, he faced racism. He wanted to join the student branch of the Mechanical Engineering Society, but was denied membership. He signed up for the newly created Civilian Pilot Training program on campus, but was told he wasn't eligible. Coach Hamilton managed to get him in, though.

After graduating from Berkeley in 1939, Williams went to Mississippi to train black pilots, who came to be known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Williams later joined the Air Force and retired a Lieutenant Colonel in 1966. After that, he taught math and was a coach at Drake High School in Marin County.

More African-American

history month features:

Honoring trailblazing campus faculty

Lecturer

finds traces of the South in the streets of Oakland

Home | Search | Archive | About | Contact | More News

Copyright 2001, The Regents of the University of California.

Produced and maintained by the Office of Public Affairs at UC Berkeley.

Comments? E-mail berkeleyan@pa.urel.berkeley.edu.