|

HOME | SEARCH | ARCHIVE |

|

Professor, friend recount boyhood lives

Double memoir recounts horrors on opposite sides of Holocaust’s great human divide

![]()

By Kathleen Maclay, Public Affairs

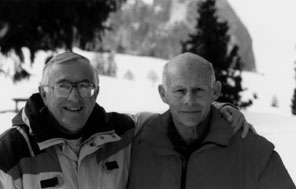

| |  Professor Emeritus of German Frederic Tubach, left, and lawyer Bernat Rosner met as adults in the snow-covered Dolomite mountains in 1999. Photo coutesy of UC Press |

18 April 2001

|

During the first decade of their friendship, Frederic Tubach and Bernat Rosner shared a fondness for crab cakes and Chardonnay, opera and culture, tennis and travel. Gradually, the professor and the corporate lawyer living in neighboring San Francisco suburbs began to explore the worlds they encountered growing up as the son of a German Army officer and as an orphaned concentration camp survivor. The result is “An Uncommon Friendship, From Opposite Sides of the Holocaust” (University of California Press, 2001), a straightforward yet moving memoir about war, genocide, courage, hope, altruism and survival as told by Tubach, a professor emeritus of German. Tubach tells the stories of two children — himself and Rosner—as they endured their own distinctive nightmares of the Holocaust and World War II. The two men began their extraordinary friendship 50 years later, when both were thriving as adults. Rosner, 69, and Tubach, 70, acknowledge that it may trouble some readers that Tubach’s voice is the one to convey the stories of the Hungarian Jew who lived through deportation, imprisonment and slave labor in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Mauthausen, Gusen and Gunskirchen. Tubach was born in San Francisco to German parents and moved to Germany when he was three. He grew up in a village struck by Kristallnacht violence, a town where many schoolbooks were anti-Semitic and from where Jewish families had disappeared by the fall of 1942. “Would this constitute a sacrilege?” Tubach asks in the book’s introduction. “… He (Rosner) wanted us to look at our pasts together, because he believes that reverence for the extraordinary trauma he experienced can sometimes have an exclusionary effect: it can bar entry, define outsiders and keep them at a distance. It can create an inner circle of empowered narratives that renders the past less accessible to others…” The system worked well, said Tubach. Rosner, who had never before told the story of his traumatic early life, recounted his experiences in detail, communicating not just the facts but also deeply buried emotions. Tubach relied on his expertise interpreting cultural texts and narrating stories, as well as on his wife, Sally, to edit his prose. “For most of my adult life, I prided myself on traveling with a minimum of baggage,” Rosner said. “I now realize that this was one of the mechanisms I subconsciously adopted to cope with the past. This project has helped me to see that the human experience cannot be fully lived and appreciated without fitting the past into the mosaic of the whole.” Tubach also believes that writing down personal experiences crystallizes them, allowing for new revelations. The stories of two young boys begins with the changing of the seasons, Hebrew school and the Gymnasium, holidays and festivals, visiting relatives and daily village life in Tab, Hungary, and Kleinheubach, Germany. In July 1944, 12-year-old Bernat Rosner and his family were shipped by cattle car to Auschwitz, where the boy was separated from his parents and younger brother upon their arrival and never saw them again. He survived 11 months in four different concentration camps by cunning, an indomitable spirit and an occasional stroke of pure luck. “In the summer of that same year, when I was 13, I was a member of the Jungvolk and slated to become a Hitler Youth,” wrote Tubach. “My father, a full-time employee of the Nazi Party, became a lieutenant in the German Army. Most of my family, including my father, survived the war.” During Hitler’s reign, membership in the Jungvolk was required of all non-Jewish boys. A rebellious yet introverted Tubach liked to conceal under his brown uniform shirt a small American flag that his family brought from the United States. He reported his stepmother for punishing him, not because she had scolded someone wearing a uniform, but because he didn’t like the punishment. Yet, he is grateful to her for preventing his admittance to the Adolf Hitler School, another stage of service for non-Jewish boys in Germany at the time. Tubach watched many Allied air raids from his rooftop and wondered when all the turmoil would end. Meanwhile, Rosner, whose weight dipped to 58 pounds when he was 13, smuggled vegetables from a concentration camp kitchen. He bartered for an extra blanket in exchange for sleeping on the floor. He tried to save his daily bread ration, having witnessed a fellow prisoner fall over and die one day while standing next to him in line. Rosner jumped a wall to join prisoners chosen to leave Auschwitz, rather than stay with younger, weaker prisoners he feared would be murdered. After his Nazi guards fled in the face of Allied troops, Rosner was moved to a series of refugee camps. He ultimately met a GI by the name of Charles Merrill Jr. Son of the founder of Merrill-Lynch, the American soldier sponsored Rosner’s immigration to the United States and became his guardian. Merrill’s mentoring helped Rosner navigate his way through prep schools, Cornell University and Harvard Law School. Rosner became general counsel for Safeway Stores Inc. in California, a company co-founded by Charles Merrill Sr. and later run by Merrill’s son-in-law, Robert Magowan. Meanwhile, in the initial years after the war, Tubach struggled to know what to do with his life. “When the war was over, everyone wanted to believe that no one had been for it,” Tubach wrote. “And no one admitted they knew about the Holocaust, or at least not its magnitude…What I heard most often was, ‘Others did it — the bad Germans.’” Tubach left Germany to join a distant uncle in San Francisco. He attended San Francisco City College and then Berkeley, falling in love with literature there. In 1954, he began working as a teaching assistant at Berkeley and became an assistant professor in 1958. Tubach got involved in the Free Speech Movement of the 1960s, working toward a faculty consensus that would neutralize the extremes shaking the campus. Tubach said he became an outsider in response to his childhood experiences, while Rosner became an insider due to his. “He’s a conservative lawyer, I’m a Berkeley leftie,” Tubach joked.

Home | Search | Archive | About | Contact | More News

Copyright 2000, The Regents of the University of California.

Produced and maintained by the Office of Public Affairs at UC Berkeley.

Comments? E-mail berkeleyan@pa.urel.berkeley.edu.